Mustang (slight return)

In a few very bumpy turns in the road up from Pokhara, languages and religions shift, landscapes morph, weather patterns evolve, and then you are in a wee corner of the geopolitical map of Nepal called Mustang, but you have entered a larger cultural region that stretches across Tibet and Xinjiang all the way to Mongolia. Mustang is embraced in a horseshoe of mountains that dip down and leave an opening like a gate to another world of high altitude deserts and ancient mythos, a ramp into Tibet; the Kingdom of Lo, the Kingdom of Mustang, into the highest plateau on Earth.

The hand was small, black, brown, and leathered, with marbled fingernails that looked like they had grown past expiration. It hung on the mud brick walls of an ancient palace armory, among rusted swords and dusty masks. If it was true, then the hand belonged to a King and was over 700 years old, preserved by the dryness of the high altitude rain shadow of the region of Upper Mustang, so I was hesitant to touch it. Many things here are a mixture of fiction and fact, “History is like this” my friend Mingmar tells me over and over again, usually after something that is suspect. He is careful not to mock as he is a believer, but built within this particular style of buddhism there is a user friendly awareness of illusion, a playful superstitious tool that is both wonder and deception and knowledge; modifying fact to such a degree that it resembles truth more than reality. The realm of poetry and imagination.

The distinction between symbol and actual is not clear in this part of the world, a statue is an extension of that which it represents, and is treated as such. Paintings of things are, in part, the thing itself. Ideas as well come to life in ritual, song, and dance. Grains of colored sand are periodically placed in geometric collections and patterns mapping out imagined temples and houses for gods. These are called mandalas, and are mind maps of heavenly spaces. Usually these mandalas are about the size of a pool table and take weeks to finish prior to a ceremony or puja. Not only that, but a mandala will bring to life a place to house gods and spirits for specific rituals. It is both a map of space and the becoming of the space in the metaphysic; necromancy, wizardry. The idea of Mandala isn’t limited to colored sand either, one can think of religious regions as a mandala, and Mustang is one of these, the stories of the landscape holding events and histories that come to life as one passes through the space and imagines the mythos. Much like songlines. “History is like this” Mingmar says again.In the 8th century, a buddhist master from India named Guru Rinpoche was invited by the King of Tibet to Lhasa in order to establish Buddhism across his country through building a monastery and temple. This pilgrimage was through Nepal to Mustang as it is the most direct route, that ramp into the Tibetan plateau, and spiritually important as there were known to be evil spirits in this valley that kept Buddhism from reaching the heights of the Tibet. Evil spirits and demons who corrupted the minds and hearts of those in the valley. Guru Rinpoche battles these evil spirits for a number of years throughout Lower and Upper Mustang valley, leaving behind evidence of the battles, intestine and blood marks left on mountains seen through stacked rocks and red oxidized copper deposits, hearts buried in temples, decapitaded heads on hilltops, auspicious temples and strange geological anomalies in the shape of footprints. Each village going up this valley has relics of the supernatural battles, totems, mandalas.

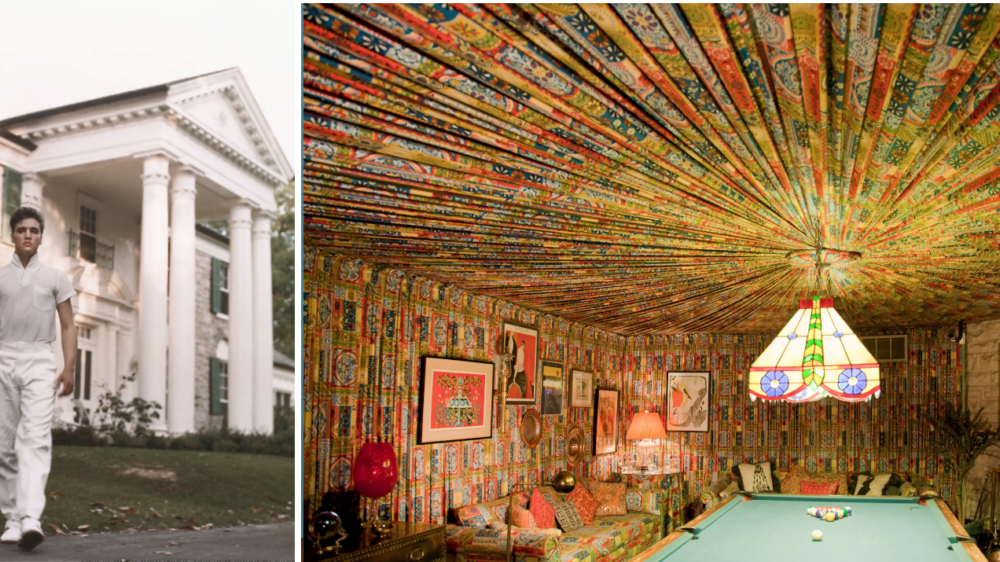

I am invited in the village of Jomsom to a temple where 5 treasures of Guru Rinpoche are kept, wrapped in silks, in a treasure chest under lock and key. A boot of the religious leader, a miracle stone he pierced with a stick, a human skull plate; objects that are coveted and loved and used to bring to life a connection with the blessed. It reminds me of Graceland and Elvis, there is something akin in the keepings of things to have some sort of connection with a time, a person, an idea.

It is said that Jimi Hendrix came to Jomsom in 1967 for a month. Marijuana grows freely here, and in those days it was legal to smoke. Much like Guru Rinpoche, there are stories and histories of Hendrix in Jomsom, inspiration for him to write the song Voodoo Child (Slight Return). It doesn’t matter that Hendrix never actually came, that he was on tour in Europe in the time he was supposed to be hanging in lower Mustang; this is moot. The imagined mythos needs no grounding in the actual to still be effective, to still draw people here to rent Jimi’s room, and to feel something. History is like this.

It is a harsh environment in the good season, the dry warmer months. The winter season, especially for Upper Mustang, is very difficult and makes the villages more and more transient or seasonal. The villages clear out for the winter, many going to Pokhara, coming back up for tourism season. This is not a new trend, this is a place of pilgrimage, a place of passing through, and a place in between.

It would be easy to imagine the Kingdom of Mustang to be static, to use phrases that equate it to some medieval time warp of a travel destination. “Come to Mustang and step back in time.” That would be a mistake and a misunderstanding, something that happens in tourism far too often, want for the lost and forbidden, a lust to magnify an otherness that just isn’t there.

In reality, there are deep connections with Mustang / the Kingdom of Lo with places like Dubai, Dallas, and New York. The second largest community in the world of people from Mustang is in Queens – New York City, a block or two away from the second largest Sherpa community in the world, and a further block from the largest Bukharan Jewish community in the world. Mustang is not a region cut off, this is a region inherently connected, like a keystone or puzzle piece, it is a trade route, the ancient barons of the salt trade would run through here, Mongolian commerce, Chinese, Indian, and a large historical connection with the modern American military industrial complex. Here you have a geographic combination of overland routes from Tibet to India, as well as rich Uranium deposits, making this a focal point for the CIA for a number of years.

Mingmar stops often along our route from Jomsom to Lo Manthang, at houses and Inns and tea houses. He always brings gifts to give and exchange. Used jackets from past trekkers, satchels of food from the low lands. In exchange he gets Chaang, a homemade brew of barley water and millet, which he enjoys. He also carries tea like an old trader from Yunnan to Kathmandu. Mingmar was born in Tibet, and left mid-teens to come to Mustang and Nepal. He now lives in Kathmandu but has a taste for Himalayan tea and keeps the trade routes of the ancient salt and tea trail open with each tourist group he guides back to his old home, turning the tourist transport into caravans of goods yet again.

It is festive season as my trip coincides with Tenchi/Tiji in Lo Manthang, a three day blessing or puja, an abbreviation of the word “Tempa Chirim” which means “Prayer for world peace”. These days there are two Tenchi’s, one in May for the wide world to witness, and another in June for the locals in the valley. It is hard not to think the distinction is due to the numbers of onlookers that are now here for tourism, to watch the blessings, to see ancient religious ritual outlawed a few miles north in Tibet, the verboden. To have one event as performance, outward facing, and one as religious process, inward.

As you drive the dirt road up Mustang you can see the preparations of pavement coming soon. There are metal towers stacked in piles ready to go up as telephone and electric poles, new bridges being built across the glacial rivers. When the 6 hour drive up the valley to Lo Manthang turns to 2 things will surely change. In 2017, Nepal imported the highest number of backhoe loaders and excavators ever purchased by any country in South Asia. This was due to a 2015 constitutional decree which emphasizes decentralized economic growth and includes a directive that roads be constructed to remote settlements, putting Mustang back in the path of world currents and infrastructure trade routes. The funding of this building boom coming from international development agencies, the Nepali government, and foreign government investments, namely China, which has large interests in paved roads from Tibet to India as part of the Belt and Road initiative.

On the way back down from Lo Manthang Mingmar introduces me to another Mingmar, it is a common name. This Mingmar is a monk and the gatekeeper to the old Royal palace in the village of Tsarang, the capitol of the region prior to Lo Manthang taking the cake. The two Mingmar’s greet like the old friends they are and we walk to the palace locked up on a hillock near the village. It looks like something from Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal, I remember crows flying from the top as we approach even if they might not have been there; they would have fit perfectly and my memory is faulty.

We climb up stairs cut from split timber, a tree cut in half and little steps shaved into one half. And we enter a shrine and an armory where we see the hand hung on the wall. The Mingmars argue about different stories they have heard, where the name Lo Manthang came from, why the Royal family left this place and moved there, demons slain by Guru Rinpoche. I know that I am leaving the valley, on the way back down after having spent a few days near the border with Tibet. I know that it will be some time before I return, if ever, and I wonder which stories will last, which ones will be forgotten. What this place will be like with paved roads. The gatekeeper Mingmar likes me and gives me a gift of a white silk scarf. He places it on my neck and tells me that this is a cheap gift. It is true, the white silk scarf is given often in Nepal, when checking in to a hotel, when leaving on a trip, at events, it is quaint and nice but easy. The monk Mingmar tells me that this is a cheap scarf but it can have meaning, that I need to remember meeting him and the hand and the stories he has told. He instructs me to hang it when I get back home over a photo of me and my family, to attach meaning to it and make it something other, the physical transcends to the metaphysical.

Travel in a place like Mustang necessitates a letting go. A letting go of timing and schedule and control. It is old school travel, it is fluid, and it reminded me of something I miss in travel these days, a DIY punk-ness to it, true grit and the enjoyment of discomfort and openness. Time that is not productive, “wasted” by transferring from point A to point B. I forgot how much I enjoyed not being productive with my time, to be bored and to be comfortable with it. The landscape is so vast and tough here it takes charge and you are subject to it, and you can’t force anything upon it. At best it allows for spontaneity and discovery, and like a child with oodles of time, it allows for imagination to take hold.