Portrait of Cornwall

Cornwall is a ruggedly beautiful, curious and varied land, and, with the exception of its interminably windy little roads, presents the curious traveller with a perfect fortnight’s exploration.

Cornwall is the toe of Britain—the south-western tip beyond the river Tamar and the English county of Devon, jutting out towards its point at Land’s End. The last native speaker of the Cornish language died in 1777, but a strongly independent character remains and has always characterised the county. Cornwall gazes at England—the ‘people next door’—as an entirely different place where the cream (so extremely delicious in Cornwall) gets worse and worse and the people more and more incomprehensible the further you go.

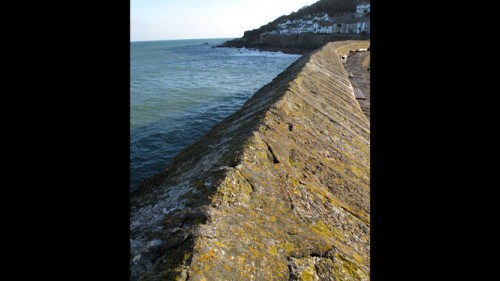

It’s an endlessly rolling and windy land. The first chapter of Claude Berry’s ‘Portrait of Cornwall’ is entitled ‘Up-Along and Down-Along’ and gives you an idea of the topography. Driving 20km here can easily take an hour as you wind down country lanes with hedgerows rising several metres above the roof of your car. Geologically the county is made up of a sea of clay-slate that’s been punched through in five places by molten granite rock, forming the Cornish ‘mountains’ (though at 300m high they’d not earn that name anywhere else). The largest of these granite islands is the whole of the Land’s End peninsula, where the great rock cliffs and boulders face the full brunt of the Atlantic crashing in, and also provided the Cornish with the masonry to build their distinctive 20-ft thick harbour walls.

For the walker, the coastal paths are a godsend. Excellently sign-posted, and covering more or less the entire of the coast round the county, there’s months’ worth of hiking to be done from village to village and along cliff tops. Inland, too, are excellent walking paths, joining the quieter villages and ranging along narrow valleys past abandoned tin-mines and curious mud-splattered farms.

They used to say that the devil wouldn’t dare cross the river Tamar from England to Cornwall in case some enterprising Cornishwoman would cook him into a pasty—a strange culinary form of self-defence that doesn’t exactly speak volumes for the tastiness of the Cornish pasty. Myself, however, I suspect that if he ever did cross over, and stumbled on a Cornish cream tea of thunder and lightning—a heart-stopping combination of Cornish clotted cream with treacle on ‘split’ cakes, he’d never go back.

I’ll sign off with Claude Berry’s hymn to Cornish cream, in which he also captures the proud independence of the Cornish:

“Does one still have to emphasize that when a Cornishman talks about cream he means cream, and not the “milky trade” which upcountry people pour from little jugs over their fruit, puddings and jellies? Devonshire people are much more knowledgeable about cream than any other English folk: indeed they entertain the curious notion that, in this matter of cream, they are the people, and that Devonshire cream, instead of being the sincerest form of flattery, is the real thing. It is too late in the day to hope that this question will ever be settled to our mutual satisfaction, so I will merely affirm that while we have, in the Devonians, the best neighbours Providence could have given us, we have also the best cream”.

Some Cornwall essentials:

www.fathen.org

www.tresanton.com

www.oldcoastguardhotel.co.uk

www.rose-in-vale-hotel.co.uk

www.luggerhotel.com

Jack did not happen to bring any of this fabled cream on his recent visit to our Toronto offices. You’ll have to go over there and get it yourself. You can place your import orders for Jack’s next trip to Canada here.