The draw of the trá

At over 3,172 kilometres in total, Ireland’s coastline is the longest per head of population in Europe. That’s a lot of sheltered, stony coves, and blustery, sandy strands for not a lot of people.

Growing up near a seaside village where others flocked to on holiday, the most important question was often: “which beach should we go to today?” Tides were important. By the time you could see whether it was in or out in Fennells Bay, you had already crossed over the wooded bridge and were half-way down the overgrown earth track. Too late to turn back then, but at least the rock pools would be full of whatever the sea had left on its way out. And there was always the option of walking under the cliffs, across to Myrtleville beach, as sandy as Fennells is rocky, and with the added attraction of ice-lolly from the post office on the walk home.

Part of the haven coast, this section of Ireland’s southern coast is book-ended by Crosshaven and Crookhaven, in the county of Cork. Some of my favourite beaches to swim off are along this stretch, especially on the approach to Bantry in the west. Spotting the black-and-white signpost in the hedgerow is only the first hurdle to overcome on the approach to Ballyrisode. The road down to the beach is narrow and you have to be prepared to play chicken with oncoming cars. The tide is less of an issue for swimming off its white sandy shore, but when it is fully in, you’ll feel braver about jumping off the rocks. At low tide, small standing stones said to mark the graves of sailors are visible. We’re told they died in a moonlight battle while fighting Canty, the local pirate whose ghost still haunts a nearby cove.

Over the headland in Kerry, the coastline is spread out, like swollen, outstretched fingers, across five peninsulas. The beaches too are wide and long and impossibly sandy, especially those surrounding the busy and buzzy town of Dingle to the north of the county. I spent barefoot summers on many of them as a teenager, lured by the promise of improving my Irish language skills (gaelic is still spoken here) but more time was spent on the trá than in the classroom. Sand dune warrens provide beaches like Castlegregory some shelter; others are more weather-beaten and waves that big are an attraction. Inch and Banna, previously better recognised as the backdrop to the 1970s film, Ryan’s Daughter, are now more likely to attract camper vans of Dryrobe clad surfers and a procession of food trucks, than bus loads of retired tourists.

The further up the west coast you go, the more challenging the waves get. Although the coast of Clare is more widely known for its cliffs, the exposed expanses of Lahinch and Spanish Point make them a mecca for longboard surfers all year round. The sands of the latter, blue-flag beach hides the rocky shoreline, on which ships from the Armada floundered in 1588 when they were blown off course. The Atlantic unleashes its full force here with waves, described by poets as ‘wild, with foam and glitter.’

Good luck trying to find the only surf spot in Connemara. Keen to keep it to themselves, the locals vaguely gesture towards Dun Laughin and talk in low voices about a beach with distracting views and unspoilt conditions, tucked away down an old dirt track with only the odd, curious rabbit for company. Hitchhiking around the north west one summer, I came upon the more sheltered, sandspit beaches of Gurteen and Dog’s Bay, having been offered a lift by a local on his way there, as long as I didn’t mind sharing with 2 suspicious greyhounds and a backseat full of fishing rods.

This stretch of coastline, from Galway up to Mayo is characterised by its bays and calmer seas. Here, activity centres offering sea-kayaking, wind surfing and coasteering are kept busy with locals and visitors alike (and swatting off midges on warmer days). Everywhere you look, there is an off-shore island or mountainous headland all competing for your attention. Bertra beach has the attraction of being watched over by Croagh Patrick – Ireland’s holiest mountain (yes, there is such a thing) and being a short distance from Westport, with its attractive, Georgian town centre. The Great Western Greenway bike trail starts from here and promises traffic-free cycling along the old railway track up to Achill island.

Once you cross over the land bridge, keep going and follow the roadsigns to Keem, passing the sheep flecked golf course of Keel and brace yourself for the ascent up the mountain pass. An optimistically placed bench makes a natural stopping point on the way but if the climb doesn’t leave you breathless, well the views…. If I had to choose only one beach in a country renowned for its sandy coves and commanding cliffs, it would probably be Keem but that would be as much for the road that leads down to it, as for the horseshoe bay itself. Often listed as one of Ireland’s best hidden beaches, this has changed since Banshees of Inisherin was filmed here. Go anyway and you won’t regret it, and if it’s cliffs that attract you to this part of the world, park the bike and head up to Benmore for views onto Croaghaun.

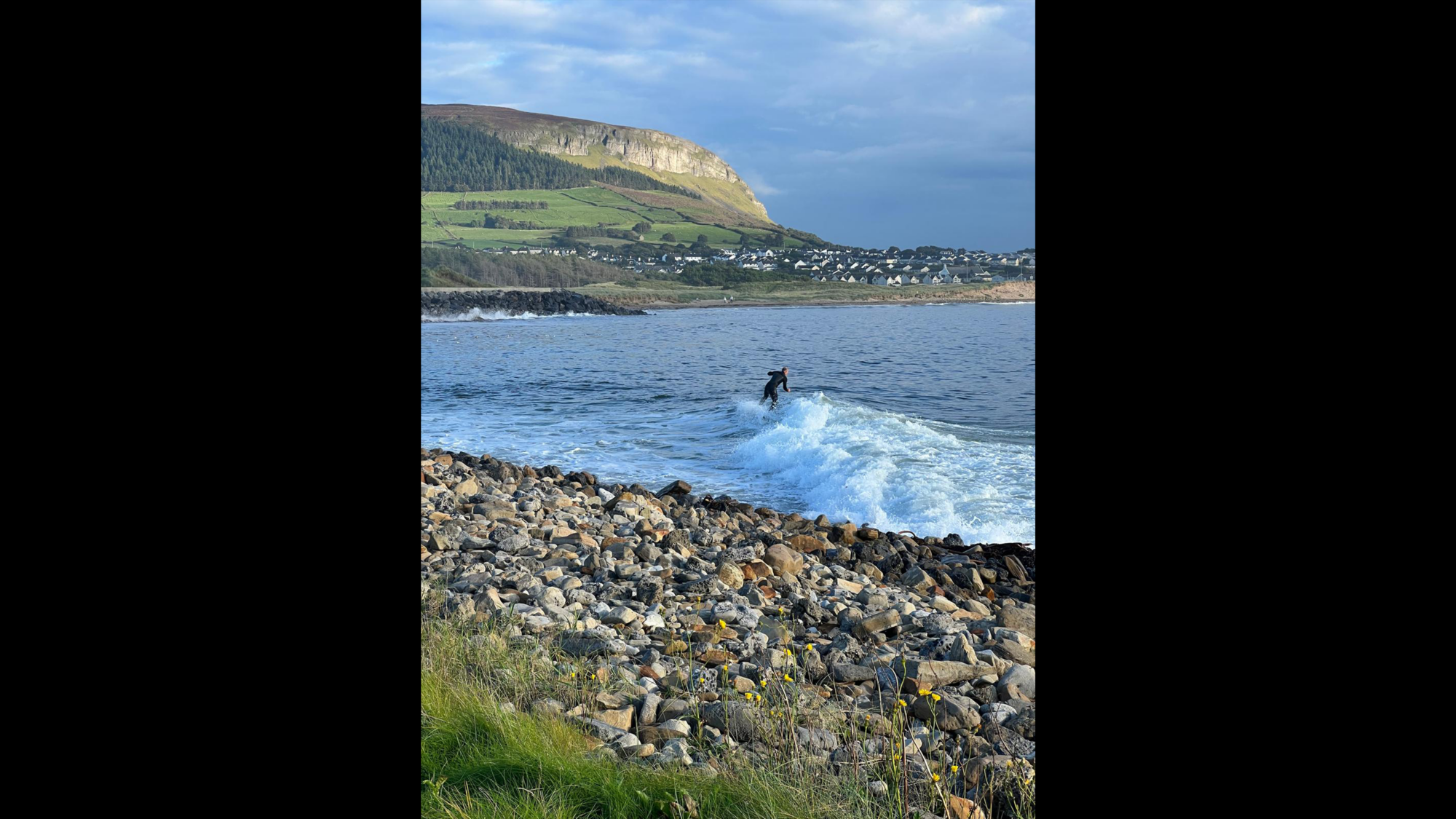

Moving north to Sligo and the Atlantic is back in full force, leading this stretch to justify the title of the ‘surf coast’. Whereas the swell off Easky will satisfy the most advanced surfer, saner sea swimmers prefer Strandhill, on the approach to Sligo town, where amenities such as cafés and craft shops smooth the post-surf come down. Voya seaweed baths started here and now, every coastal village worth its salt boasts some version of the seaweed and warm sea water combo.

I won’t go on, but you definitely should – to the Mullaghmore peninsula with the Benbulben mountain backdrop, and further north again, to Donegal and Slieve League, seemingly the highest cliffs on the island… but you can decide for yourself.

The Irish go swimming and surfing and enjoy other sea-based activities all year around which means that beaches are active places, not for lying around on! Sure the water temperatures are cold but the Gulf steam (and a bit of bravery) helps!