The Good Old World

When people coined the phrase ‘New World’ in the 15C, I wonder if they expected those impertinent New Worlders would one day repay the favour and start referring to them as the ‘Old’. The Older the better, we say.

The Old World wasn’t always the Old World. In the 15C, Europe and Africa was less modestly referred to as ‘The World’. It was the seat of all wealth and power in, well, pretty much the entire known universe. And it always had been. The New World—nova orbis—stood in direct comparison: it was an untapped wilderness, savage, new and unknown, and there to be plundered.

Things have changed. ‘Old World’ now tends to imply small-scale, hand-made, traditional, (or if you’re talking about hotels it means dusty, dark and dank). It can mean craftsmanship, character, uniqueness. But there’s an implied sense that it doesn’t hold up against efficiency and scale. In other words, it’s quaint and we kinda like it, but it’s no proper way to run things.

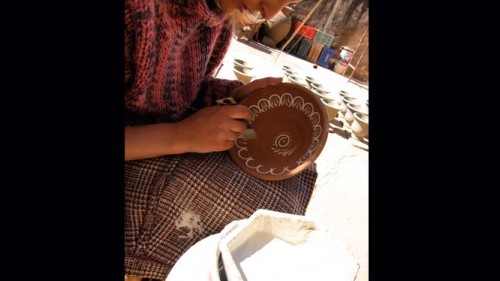

Old World charm, however, is what brings curious travelers flocking to Europe on holiday—not so much for the titanium buildings, CERN and the Eurostar, but to see crumbling palazzos, buy hand-woven baskets, and eat slow food. So at Trufflepig we spend a lot of our time talking to potters, farmers, cheese-makers, and, yes, even donkeys.

But it often seems like a sort of deliberate act of denial and over-editing to travel around Europe and ignore anything that’s not mediaeval and handmade. After all, they have Ikeas and McDonalds here, too. So why do we do it? Are we looking for these places just because they’re charming and quaint and picturesque?

Actually, no. We have a somewhat more hoity-toity approach. We’re loca-whores. We like to plan trips involving the most interesting local people doing the most interesting local things, and we like it most when things are different and olde worlde as can be. Why?

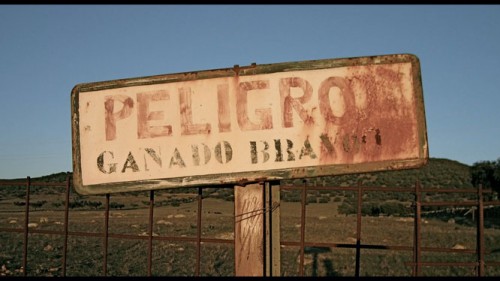

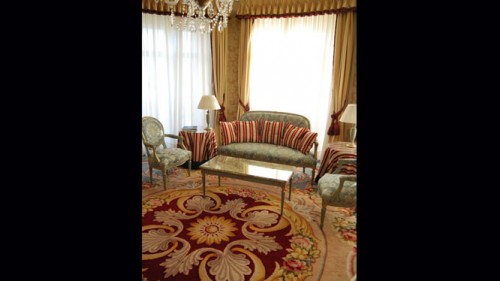

Because these activities are precisely what keeps the landscape looking the way it does, what keeps people in the towns and villages, and what keeps the places that we like to visit lively and interesting, with kids in the schools and with locals in the bars and restaurants. The acorn forests in Extremadura, the kid playing in the street, the man throwing pots, the guitar maker, the bull farm, even the hand-made carpets of the Ritz in Madrid—all these things require and create a economic and cultural setup that, put very simply, we really dig.

So when we do our trip research we set out very deliberately to find these sorts of people. They run restaurants and they own hotels, they farm and they make things. We stay in their hotels and eat the food they make, and we drive all over the countryside looking for people doing strange things with cheese. We consider it our bounden duty to drink barrels and barrels of sherry and eat plate after plate of jamón. It’s not the normal activity of a travel agent, but it is the proper activity of a Trip Planner trying to get to the heart of what is most exciting and unique about Europe.

Jack runs our European Trip Planning desk from Paris, and is trying to save the world, one 4-hour lunch after another. If you’d like to join his quest, email him here.