waterlogged

“They’re feckin’ crazy for it, the whole island, two years ago you would find no one out there, now, twice a day, heaps of em.” – Pat of Inis Meain.

During the various covid lockdowns in Ireland a trend took hold, and something elemental and primal came to the surface in this island country: the need to wild swim. Pat was telling me about this as he saw me walking back to my hotel after a swim in the Atlantic. I’m on Inis Meain, the smallest of the Aran Islands off the coast of Galway, the far edge of Europe, on St. John’s eve. He stopped me in the road and told me I had to talk to his wife who ran the “dry robe brigade” on the island, a wild swimming group that met twice a day for a swim on the old pier, rain or shine. He dialled on his cell and then handed me his phone and Martina on the other end of the line told me where to be and when, and said I had no excuse, I had to come with them.

I felt the same pull in Dublin a week prior, and took the city train to the coast for a swim on a rocky staircase that looked like the Amalfi Coast. Those there were mostly local teenagers, complete with joints, and radios, sitting in the sun. It was glorious and a touch wild (although not that wild, Harry Styles a few days later came down to the same spot for a plunge). I have been coming to Ireland for years, spent some time surfing on the west coast and had never seen this much attention to wild swimming from the communities living on the coast. But now, after a couple of years of lockdowns, we all were forced to get to know our backyards a bit better. In Toronto many went to the wonderful ravines of the city, mountains turned inside out, depths of waters work on land, exploring and micro-adventuring. I started reading old travel books (nostalgia) and I also was reading essays about landscapes , and then was handed a Roger Deakin book, Waterlog, written in 1999. It was a book inspired by John Cheever’s short story, “The Swimmer,” a story about a man who swims home from a summer party through all the back garden pools in the neighborhood, one by one, sneaking through fences, submerging over and over until he reaches home. Deakin wanted to swim wild waterways in England, from one side to the other, and in doing so was discovering new things about both himself and his place. I feel like the same thing that drew Deakin to Cheever’s story, and the thing that drew me to Deakin, and the thing that grabbed the attention of the Irish population, was the elemental essential quality of water and wild. I know this makes me sound like Brig. Gen. Jack Ripper in Dr Strangelove “fluids mandrake!”, but follow me here, it leads somewhere.

Perhaps it is the flow of the north Atlantic current bashing into Ireland, a steady stream of waves and energy, moving freely for miles via wind and water, motion, fast, flowing, and free, ending abruptly on rocky shores, where does the energy go? Or it could be a mixture of pagan, viking, druid, and catholic religious systems, ideas actualized by groups of people believing; I am not sure, but there is a bending of both time and space that happens in Ireland that I am still trying to understand. Landscape plays tricks on me here, things look close, but are far, flat fields have hidden valleys that can only be experienced by walking through them, there are nooks, twilight zones and microcosms. For a small Island, there is depth and variety in geography. I am coming from North America, where land is vast, and seemingly slow changing, the east coast moving uphill to the Appalachians then down to the headwaters of the Mississippi, then the slow climb up to the Rockies through the prairies, then the west coast, miles and miles of slow morphing land. In Ireland, a few steps can change a climate. Hidden in the landscapes are sacred places, dream soaked crannies that are, in part, not of the physical realm, but are of the spiritual or supernatural.

I want to be careful here with words. When I write things like Fairy, Leprechaun, Elf, a cartoonish caricature pops up in the mind, something fluorescent, but when those words first appeared in the lexicon, they were more used to explain something that had no other words to explain; they became cartoonish later, like when a teenager makes fun of their own stuffed toys in an attempt to sound beyond that point of development. Those words were used to explain the haunting feeling you get in these sacred places, where there is magic in the air, you can feel it, you only need to stand in these places to know something special is happening that we are far from understanding.

Some of these places have been secretly celebrated for a long time here, pilgrimage sites that were pre-christian. A habit of conquering groups is to go to a place that is already sacred, and reinvent it as its own. You see this in South America with the sacred places of the Inca turned into churches, you see this in kingdoms where new kings smash the old capitol to bits and have a new one rebuilt in place. But the sanctity of place seeps through no matter how much smashing happens. The saints of Peru are in part Inca gods, the old capital cities of kingdoms leave a mark that rises in the new build. Monuments, architecture, the way we organize things in the physical world leaves notes, or signs that can be read like a book if you know what to look for. I have walked through temples in Asia with guides who knew how to read the architecture and tell me when what was built and why. Like Sherlock Holmes, we can notice things that tell us our own stories. Religious sites tell a history of our communities, what we find sacred, what we hide, what we covet.

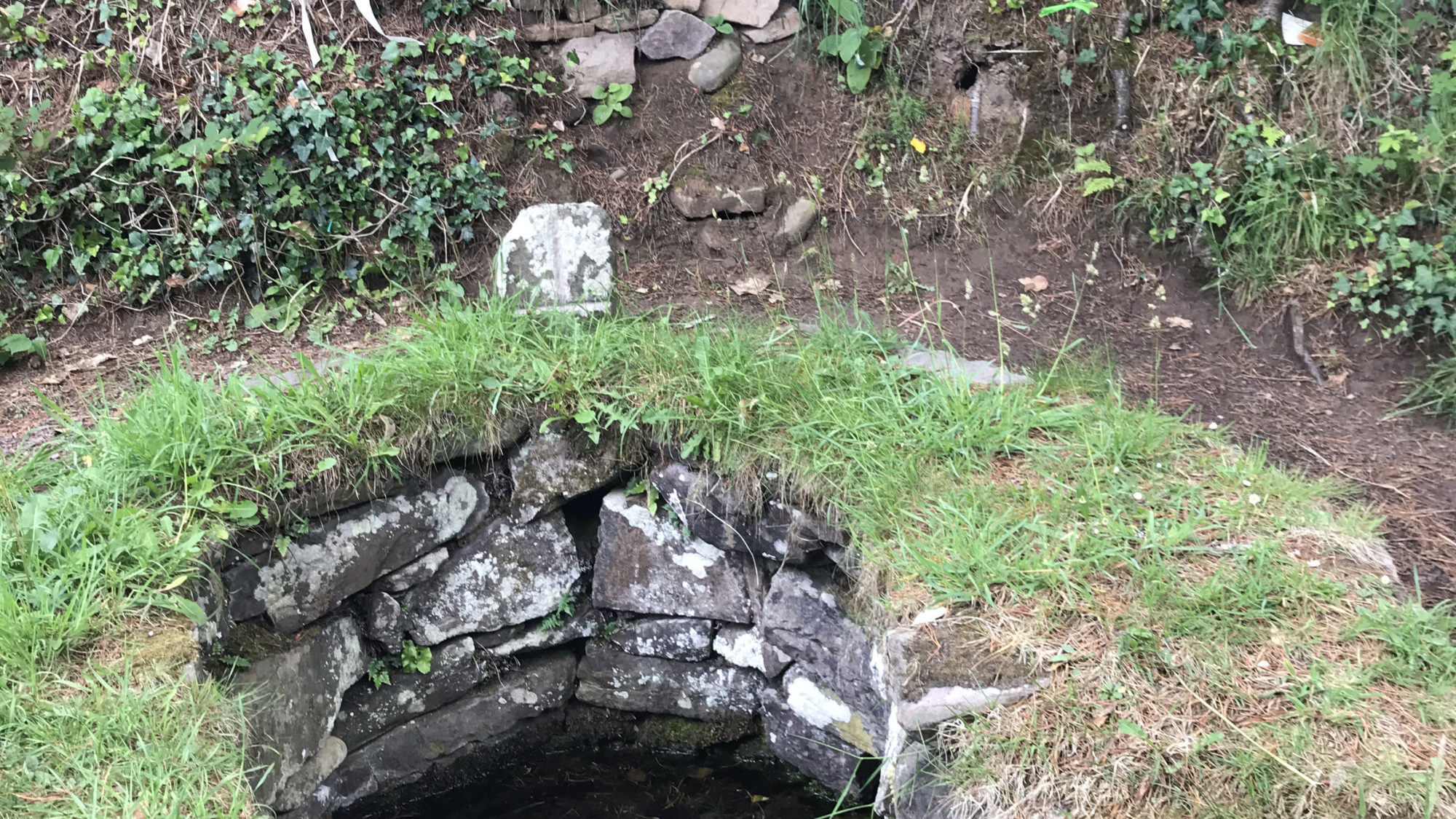

The same is true in Ireland with the Holy Wells, there is a christian veil laid on top of something very old, very elemental, very human, and we can see through it.

There are thousands of these sites sprinkled across this morphing landscape, off the sides of streets, down rocky trails, near mountain tops. They all seem to be slightly hidden, near a thick wood, and down, in a crevasse, valley, or dale. Over the past two weeks I have been searching these out, passing none if I see or hear about them, and they have provided me a reason for exploration, an excuse to go to places I would have normally passed by, like some sort of ancient geocache or pokemon go game. Some felt thicker than others, thick with that energy, that magic, some felt barren, sad, some felt spooky and curious, some felt euphoric. There is one that I swear put a spell on me. I know this sounds kooky and hippy dippy but I am reluctantly superstitious, which makes me very superstitious but I don’t like to talk about it.

I was in Cashel when I heard about it. Cashel is famous for its castle and rock formation, which was said to have come from a fight between St Patrick and the devil, a chunk of a mountain was flung in the madness and landed in the middle of the countryside. A story I have heard told in similar ways in other landscapes and mythologies, in Bhutan and in Peru, with other gods and demons. I was sure there was some deeper story that preceded St Patrick and the church, and was under the surface of the Christian story told. Then, a ticket counter at Cashel Rock told me about St Patrick’s Well, 20 miles south, so off I fled. I drove south and found a sign on the road that pointed to a Holy Well. The road turned left and went down into a pocket of land. That’s the way things move here, there are hidden corners, like snugs in pubs, the little hidden seats tucked in plain sight but not seen, the landscape does the same. The road pitched downhill and became lush and wooded, thick dark leafy. Then on the side of the road a sign and a few parking spots, and two old men, farmers, talking, while a younger woman unpacked her things out of her car, a towel and a bag, to head down the trail off the road. The trail went further down into the wood, well trodden, well stepped, and it opened up into a small body of water, moving, with a cross made out of limestone in the middle, and there were bucolic fields spreading out in three directions from the water, Olmstead style parks, and the sun shone down bright, clear, and beautiful. The pond was stoney and shallow, shin deep all over, and there were two little wells feeding into it, and on the far side, maybe 50 feet from where the stairs put you out, there was a stone temple.

I walked slowly around the space, as to not miss anything, and the woman and farmers came down the stairs followed by another man rolling a cigarette a few steps behind, staggered, all separate, all gathering to the same spot as I, this well and the water. The main well spring feeding the pond was the focal point and that is where we all congregated, a place to squat down and place your head in the flowing water. There was also a 30 foot stream from the well to the pond where the woman submerged to her hips in the cold water. “Heaven on Earth” she said to the man rolling his cigarette. “Better than Heaven” he replied.

In Ireland there is a direct line to conversing like you are old friends, you jump right in. I was quickly asked where I was traveling from and we all became familiar with each other. Jokes were told, smiles, mentions of how nice the weather was that day, and it was, it was booming. Maire came everyday to submerge, it was her spa and church all in one she said. The man with the cigarette was named Sean and he came from time to time, but used to come more often, before his son died of cancer at 5 years. They all knew his son, they all had seen him there in the waters years ago with his boat. He would come with a small boat and float in the sacred waters, frolic and play. Sean started coming back when the lockdowns started, it was religious, without being about God.

Sean told me that if I wanted a wish, to walk through the pond to the cross in the middle, and walk around three times, barefoot, so I went while they all watched. It was tough on the feet but I took my time and went slowly and steady. I was reminded of my time in the Himalayas, the circumnavigating of things in threes, clockwise, a universal urge. I stumbled back to the well up the stream passing Maire, sat on the banks and smiled. I had wished that my leg would be ok. A year ago I ruptured my achilles and it had been a slow recovery, mostly mental blocks of worry on a trip like this, a trip where I would want to run, jump, bike, and hike. I looked down at my leg and my achilles, I swear, it clicked or something, I felt something in it move, and I took it as a sign that it would be ok, I felt happy and held, and with others.

It was a wonderful space to be sitting in, sun shining, surrounded by woods, with people, real people with sad and happy and complications and ease. When the time came I said goodbye and walked up and out of the sacred place back to the road. I felt relaxed, and looked at my watch, and it was filled with humidity. I had not submerged it, I wasn’t sweating, there was no reason for my watch to be filled with droplets like I had been standing in a cloud, but there it was, a damp inside watch face from an antique manual watch my wife gave me. I took it as another sign. Something had happened down there, I was not on Earth for those moments, I was somewhere else.

In the Himalaya there is a particular landscape called a Beyul, hidden valleys that are believed to be gateways into perfection, Shangri-La. I heard an explanation once that chimed with me, that the Beyuls are lush valleys, high up, with fertile land and water and food, so in a way, in a time not too long ago, this was the idea of perfection, an easy place to live. Our idea of what Shangri-La should be shifted and changed as our lifestyles changed, but imagine living in a barren high altitude desert and happening upon a small lush valley – it was all you needed and more, it wasn’t a gateway, it was perfection, heaven on Earth. I feel like the Holy Wells suffered the same problem of expectations; that long ago, these hidden crannies were protected from the wind, had a water source, and lush wood, it was, and is, a magical landscape, a refuge.

I went to 8 wells on this trip, all in different parts of the country, the ones that had people there all had a similar joining, communing that would happen. The funny thing is, the same communing would happen when I would go wild swimming, the same joining. The geography was different, it was the open sea, but sublime in a different way from the nooks of the Holy Wells. The approach was usually similar as well, a staircase and trail going down to the waters. I would get to the swimming hole and there was an instant sense of community. It felt like what a good pub should create, an environment where an acceptance happens. Pub, short for Public House, the communal living room for villages and towns from Dublin to Dingle, where people become public.

Martina had told me to be there at 9am by the old pier so the morning after her husband handed me his phone with her on the other end of the line, I woke up, had coffee, packed a bag, and walked down to the pier. Inis Meain is a small island, you can walk everywhere. The population is about 200 people; it is small, but filled with landscapes constantly changing in the North Atlantic waves. It is one of my favorite places on earth and I am not really sure why, but it is. I walked down to the pier and saw a gathering of 4 people, in robes, and with floats, and swimsuits. The water temp this morning was around 15 degrees C (58 F), it was fresh. I met Martina, Stella, Oona, and Florian, and again, a direct line to conversing like old friends. Martina and Stella swam as often as they can, twice a day, and you can tell, they swim next to each other in a synchronized systematic way, a way done through thousands of swims together, a joint breathing, Stella mostly went on the left side of Martina, it was old and familial. I instantly realized my idea of a swim was very different from theirs, they had kit, ear plugs, booties, and pointed to a far off buoy in the middle of the Aran Islands that looked to be about 500 meters out to sea, when I thought the rush of a plunge was all that was to be had, but I was there, I was committed, and I was willing, so I swam.

At first the cold water baptized me in pain. The nerves of my limbs panicked and vibrated. But as predictably, my nerves calmed and eventually a numb warmness took hold and I was able to swim, following Florian, Oona, and Martina and Stella. I followed in the back, like a surf spot, you respect your position in the water, and your lack of local knowledge on jellyfish; some can hurt you and some are harmless. Martina and Stella swam freestyle (front crawl) and would look back to check on me every few minutes until they decided I was an able water goer. I swam the breaststroke, head out of water, happy to be ignorant of what was below and trusting that Martina and Stella would warn me, protect me. We swam the 500m to the buoy and back and it was, like the Holy Wells, spiritual, ritualistic, and wonderful. We talked and joked post swim, Martina and Stella said their group were called “Blue Tit’s and Bluebells” and invited me back for an afternoon swim at 2:45pm the same day. I didn’t think twice and said Yes.

I hope what we found, when we were forced to look close, stays in our habits and in our collective psyche for a while. I see it seeping out, with everyone eager to run far and wide, and that is understandable, but perspective is everything, and what if we are closer to our shangri-la’s than we realize, that our communal landscapes close to home have the essential things we go out seeking in far flung points of the map.

a nice water themed tune to send you off with