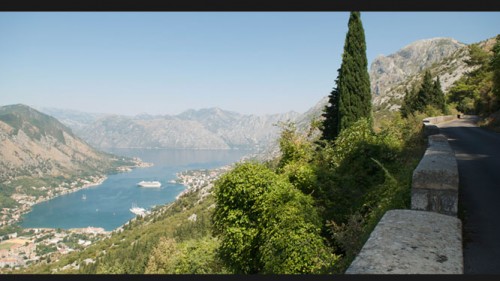

Above Kotor Bay

Parts of Croatia and Montenegro’s Adriatic coast combine some of the most stunning landscape and villages in Europe, with the very worst that cheap mass tourism has to offer. How do you see past the café umbrellas and postcard stands, to the original character of the place?

Since the likes of Dubrovnik and Kotor decided to allow enormous cruise ships to moor outside their mediaeval harbours and disgorge thousands of passengers every day of the summer for three hour shopping trips, the character of those towns has changed radically, and (I think) greatly for the worse. There’s a huge difference in the effect that a tourist staying for three nights and a tourist staying for lunch and a souvenir can have on the development of a place. As a friend who runs an excellent hotel in Dubrovnik told me, since the cruise ships arrived, the fridge magnet shops have taken over the city.

As a result, I can think of very few places where the present-day character of a place clashes so visibly with the past, as it does in these defensive Dalmatian coastal city-states. They date from a period when most people arriving by boat were armed with bad intentions and greeted with boiling oil, and their locations and architecture tell that story. They made vast fortunes controlling the trade routes of the Adriatic, and built cities to rival Venice in beauty. Now they cater to people still arriving by boat, but armed with dollar bills and greeted with flaming lamborghinis. They make a pittance out of this trade—mass tourism leaves a big footprint but not a lot of money—and concrete will be the lasting legacy.

Don’t I sound like a grump. Well, look past the postcard stands and the pizza joints. Kotor Bay in particular requires only a little effort on the part of the traveler to imagine what it must have been like arriving here in centuries past. Swap the huge cruise ship for a little boat, rentable along the coast, and make your way from the Adriatic into the inland bay, puttering along as you’re gradually dwarfed by the cliffs that rise on both sides, and block out the afternoon sun. The further you are from the music emanating from discos on the shore full of Serbian teenagers, the more genuinely awesome this is.

Continue on to Kotor, and you’re greeted by the most paranoid city-planning in the world. The town’s ten-foot thick walls are built of local stone, and almost camouflaged against the rock. It inhabits just a square kilometre of flat land, otherwise hemmed in by water, and backed up by thousand metre high rocky cliffside. No one’s getting in here by water who isn’t welcome; and from inland? Forget it. But they built a fort halfway up the cliff just in case.

So that’s where you head. There’s an ancient pathway that rises sheer up the cliff, and makes its way to Cetinje, the ancient capital of the country. It’s been replaced with 20 km of switchbacks on a road that scales the mountain, puts the entire bay in perspective, and continues to Cetinje in the inland hills. It is without a shadow of a doubt the most awesome bike ride I’ve ever done. The loop from Kotor to Cetinje and back is 100 km on the nose, so it’s quite a day. But it wiped away all my sense of disappointment in the cheesiness of Kotor’s bars and cafés—and left me with the sense of awe surrounding this mountain kingdom that I’d come hoping to find.

Jack Dancy paints pig-shaped fridge magnets to sell at a small stand on the coast when he isn’t planning trips.