Aeolian Women – A Real Catch

Here we are in a snow globe of uncertainty. At first, we read every headline. Then we retreated from the media all together for mental well-being. Some wore masks. Some went rogue. We all wonder when we will next travel? How far? Where to? Will the buoyant snow flakes of our current globe settle to the bottom any time soon? I don’t know. But I do find myself wondering where in the world can we look for guidance as solid as black obsidian rock. Politicians? The WHO? Economists? I’m not so convinced. I’ve set my sights on the badass fisherwomen of the Aeolian Islands.

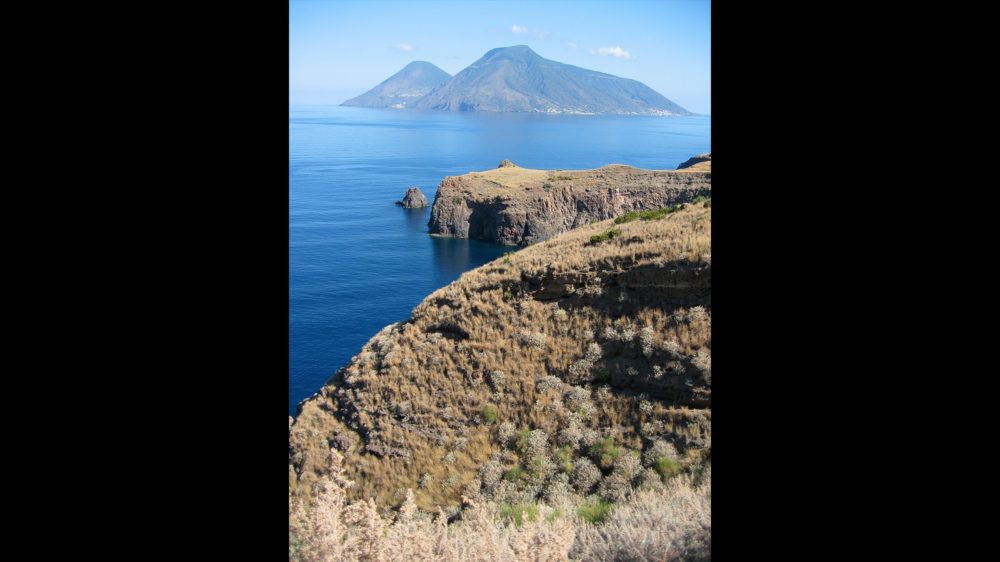

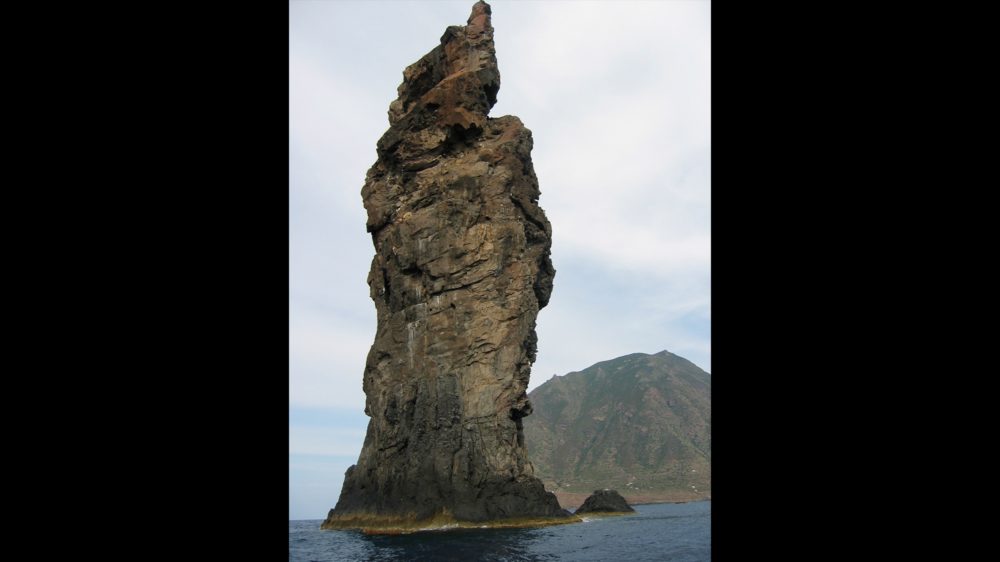

The Aeolian Islands make up a scattered archipelago located off the northern coast of Sicily, seven islands formed by aeons of volcanic eruption, where sea, lava and wind have shaped seven jutting (i)conic proclamations: Vulcano, Lipari, Salina, Panarea, Stromboli, Filicudi and Alicudi (the most remote and eccentric of them all). Just a ferry ride away from their big sister, Sicily, these jasmine-scented islands have been attacked and conquered and attacked and abandoned over and over during their long history of Arabic, Greek, Norman, and Italian rule, to name just a few. Each island has its own distinct flavour, its degree of accessibility and of modernization, depending on how the volcano crumbled and the landscape shaped over time.

What they all have in common is a shared history of fierce fisherwomen called the ‘Donne di Mare’ (Women of the Sea) who rowed shoulder to shoulder with the fishermen well into the 20th century. As portrayed in the 1947 film Eolie Bianche (minute 2:30), these Aeolian women set to sea night after night as a full female crew, looking to the stars to verify the time, to check for signs of changing winds to chart their course, to sniff out the direction of their catch: bluefin tuna, swordfish, amberjack, grouper. Macrina Marilena Maffei, an anthropologist and maritime scholar, chronicles the lives and adventures of the fisherwomen in her book, “Donne di Mare”. She has collected over a thousand documents and recorded stories narrated by the families of the fisherwomen themselves. These gorgeous oral histories, preserved partly in the sound archives of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, and partly in her private archive, have kept this history alive.

These sea-green-eyed Aeolian lasses (influenced by the Norman rule) didn’t flinch before setting out by boat, occasionally birthing babies aboard amongst fish nets and mackerel if the timing was right. Each of them motivated to prowl the waters to feed their families and contribute to the livelihood of her tribe. Rest assured, the roles of women were cast as widely as their hand-woven nets, to include conventional duties: child minding, laundry wringing, floor sweeping, vegetable growing, and let’s not downplay the dedication to cooking in these parts. But this gaggle of gals could transition effortlessly between foraging for herbs, to bouncing a bambino on their hip, to catching sea turtles with their bare hands as their bodies lunged forward like a lightning bolt towards the sea. Their grip was strong enough to firmly grasp the shell of a passing sea turtle and hold on, a black belt maneuver in the fishing world. While the women were mostly illiterate, they were highly-skilled in myriad roles, always keeping an equally fierce grip on the vitality of their community and respective families. Here is a performance by islander Guido Politi, singing about a woman named Sara who has fished for swordfish since she was a little girl, which captures some spirit of the island.

Before the curtain closed on international travel, I had the great privilege of taking a research trip to these remote islands. Arriving, I first observed the severity of the landscape from afar, aboard the ferry from Milazzo, Sicily. Imposing craggy outlines with harsh purple shadows extending down the defunct craters like geometrical claws. The sleek, glassy obsidian on Lipari gleaming like an expectant tuxedo. Angular contours under a relentless sun, like facial features refusing to soften with age. By contrast, as I drew near to the islands, I was enchanted by the luscious vegetation nourished by the fertile volcanic soil. A blaze of canary yellow cloaked the nearly vertical facades – Thyrennian broom. Lemon groves. Olive trees. Malvasia grapes. Cacti. Caper flowers with four white pedals framing electric purple filaments, gleaming like a punky Edison bulb.

I disembarked on the island of Salina, which was too beautiful to absorb all at once. Tears of overwhelm rolled down my face for the entire first pass along the ring road of the island. There was only one thing to do. Find an Aeolian fisherman, with the tranquility of water in his eyes, and start asking questions. What I’d anticipated as a morning visit over coffee unfolded into a full day of storytelling, visits to caper producers, wine makers, old friends and an introduction to the mayor herself. We met a vivacious woman who stood bent at the waist almost 90 degrees, from having harvested 800 low-to-the-ground caper plants each year. We met a bus driver who knew the name of every local who climbed aboard, as well as the dog who gunned ahead to outrun the bus. Our exploration continued by sea that afternoon, where I learned of the traditions passed down from generation to generation, and the challenges facing modern day Aeolian fisherman as our modern world clips along. As the afternoon light became more golden, we headed for the fertile patch of land in the Val di Chiesa that lies like a hammock between the two volcanic peaks which define the silhouette of Salina. It was here that we foraged for wild fennel to serve with pine nuts, raisins and freshly-caught mackerel in the pasta for dinner that night, in a typical Aeolian home. One should never underestimate the enormous hospitality of Italians. It was around that very table that I first learned about the women of the sea.

What if we could combine all of this fisherwomen mojo, with the additional feather of literacy in our caps? Mightn’t we find our compass and sea legs through these treacherous waters? Peace and competence. Intuition and bravery. Trust and elbow grease. Acceptance of utter uncertainty. A studied glance to the stars. A commitment to community and a healthy social order. A good handkerchief, a red net, a tight village and a healthy grip at the ready for when the next great opportunity swims by? I think we’ll know when it’s time. And nobody should let go of an opportunity to visit the Aeolian islands.

While others baked bread and bit their nails during quarantine, Meredith learned to knit nets with her bare teeth and antique fishing spears.