Bon… jour?

No one can complicate things like a Frenchman can. Just when you thought it was as easy as ‘bonjour’, here’s our abridged guide on how to say hello in French, reduced to 17 easy-to-remember time/gender/location/religion-specific steps.

Think of bonjour as a launchcode: dangerous when it falls into the wrong hands. That’s right, although they taught us at school that bonjour means hello, what they failed to mention is that you need to fully understand space, time, politics and gender before you’re licensed to use it. So sheathe that salutation, mon ami, and read on to go from débutant to maître.

Below is our everyman’s guide on how to greet a Frenchman or woman, or say hello to a line-up in a boulangerie, or to address a group of striking farmers blocking the autoroute – or indeed any other everyday French situation you’re likely to come across on holiday.

As elaborate as this may seem at first glance, it’s a vital way to appear friendly and confident as you approach The French, and to establish a rapport, even if you immediately drop back into English afterwards, or ask for a peacock when you were trying to say loaf of bread.

The key is that to greet someone correctly in French is relatively simple, but saying goodbye is devilishly hard. By the same token, English is also more complex than you might think: you wouldn’t say ‘have a good day’ to a waiter as you leave a restaurant after dinner, while you might (if you were a character in a Dickens novel) say ‘Evening all’ as you walked into a pub at 3.30pm in a Yorkshire winter. I.e. we have our own nuances, too.

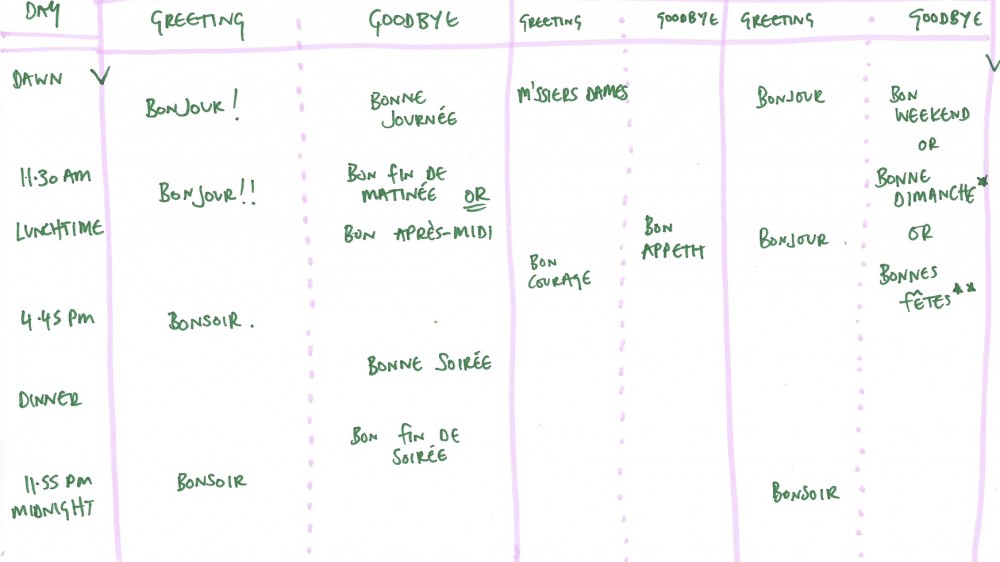

Please refer to our patented Bonjour-o-meter (in the slide-show above) if you are a more visual learner.

Some of the variables to be aware of at all times while you are in France are: exact time of day (of vital importance); day of week (essential); holiday/feast-day/workday (fundamental); type of establishment (subtle but important); opening and closing times of said establishment (advanced); relative social position and/or religion of interlocutor (elementary). Using our charts below, and/or the bonjour-o-meter, and bearing in mind these simple variables, you will be able confidently to boom out your Bon Dimanche or your M’sieur Dames as comfortably as any Lino Ventura, himself proof that French language and culture can be conquered by a foreigner*.

Weekdays

• Until 11.30am – general use

Entrance: “Bonjour” (good day)

Exit: “Bonne journée” (have a good day)

From dawn to 11.30am is the easiest time to greet a Frenchman. If you are a beginner, we suggest doing the majority of your shopping and indeed all social interaction during this period, until you have built up confidence. Bonjour on the way in; bonne journée on the way out. Obviously.

• 11.30am to lunchtime – boulangeries and shops that close for lunch.

Entrance: “Bonjour”

Exit: “Bonne fin de matinée” (have a good end of the morning).

At 11.30am, the waters begin to get murky. If you are in an establishment which closes for lunch, it makes sense to wish someone a fine end of the morning. For everyone else, read on:

• 11.30am to 4.45pm – all humans except shop-keepers, and including restaurants for lunch.

Entrance: “Bonjour”

Exit: “Bon après-midi” (have a good afternoon)

If you are talking to a friend in the street, or a waiter, or a cheese-maker in the Alps (for example), you can stick to the dependable bonjour, but must be aware that your departure will be more of a minefield. Given that you’ll be parting company with someone who still has a sizeable chunk of their afternoon to come, you may wish them a ‘bon après-midi’ without risking any insult. Bonne fin de matinée (above) would be lacking in generosity with your well wishing. If they’re tucking into a sandwich, you’re in luck and can pipe ‘bon appetit’ (see variants, below). Or, you can simply avoid going out entirely from 11.30am until early afternoon.

• 4.45pm to 11.55pm or 5 minutes before closing time (whichever is later).

Entrance: “Bonsoir” (good evening)

Exit: “Bonne soirée” (have a good evening)

The evening begins very early, and from around 4.45pm you can begin to wish a good evening on people. Bonjour at this point would be absurd, naturally. There exists an unspoken one-upmanship whereby the earlier you wish someone a ‘bonsoir’ the better a human being you are. The true master will take into account the season and sunset time when calculating his bonsoir threshold. On the way out, bonne soirée is the bonsoir equivalent of bonne journée, bien evidement.

• 11.55pm or 5 minutes before closing time (whichever is later) onwards

Entrance: “Bonsoir”

Exit: “Bonne nuit” (good night)

Curiously, the evening retains its grip on time well into the nighttime greeting, even if you’re walking into a bar at 2.30am hoping for a cleansing beer. However, on the way out, if you’re wishing farewell to someone whom you sense is about to go to bed, you can dare the slightly intimate ‘bonne nuit’. This creates genuine rapport and says “we were here at this final moment of the day together, unknown Frenchman, and we shared it with this carefully chosen expression. We are brothers.” However, used too early, and it simply seems like you should be in pyjamas and clutching a teddy bear.

Variants:

• Any time of day, when addressing a faceless crowd:

Entrance: “Messieurs dames” (morning all/evening all)

Exit: time and location appropriate exit salutation from above

This greeting will elicit a mumble in reply from the politer members of the crowd. It’s handy when walking into boulangeries where you can’t immediately get the owner’s attention. Depending on how old-school you are feeling you can shout it out, or mumble it into your beret as you remove it respectfully, and decide which pastry to buy. Be warned, you will still need to use the appropriate person-specific greeting from above when it’s your turn to get served. “Messieurs Dames” is technically a pre-greeting.

• To anyone about to eat something:

Entrance & Exit: “Bon Appetit”

Perhaps the only truly bilateral salutation, bon appetit can be used on the way in or the way out, as long as it’s said to someone who is about to eat or still has food on their plate or better yet actually has a mouthful. Said to a couple in a restaurant who are drinking their coffee and paying their bill would be mildly insulting.

Weekends, Civic Holidays and Religious Holidays

• Saturdays from dawn until 4.45pm

Entrance: “Bonjour”

Exit: “Bon weekend” (have a good weekend)

Bonne journée loses its status on Saturdays, and is trumped by a larger and more generous wish that your interlocutor pass broadly a good weekend not merely a good day. This is a very republican sentiment.

• Sunday mornings until 11.30am

Entrance: “Bonjour”

Exit: “Bon dimanche” (have a good Sunday)

That largesse d’esprit diminishes on Sundays, where you wish someone a good rest of the day, specifying that it’s a Sunday, but offering them no solace for the Monday which will inevitably follow. N.B. from 11.30am on Sundays onwards, you revert to the weekday farewell, because of course no one wishes to be reminded that Sunday is nearly over.

• Major holidays (Christmas, NYE)

Entrance: “Bonjour/bonsoir” (see above)

Exit: “Bonnes fêtes” (party hard)

Bonnes fêtes is an excellent catch-all, and if you’re feeling the spirit of Christmas, you can start dropping it in several weeks prior, any time you think you’re seeing someone for the last time before dawn on December 26th. It’s the nec plus ultra of French salutations.

You can tack an “au revoir” (formal) or a “salut” or “ciao” (informal) on the end of any of the exit phrases. Eg “Bonne soirée, ciao” or “salut, bonne journée”, or “bonne fin de matinée, au revoir”, to spice things up.

Really it couldn’t be simpler and these basic rules are well worth the hours spent mastering them.

Au revoir, and bon courage.

*Throughout his career, Ventura (an Italian) was one of the most popular actors of French cinema. He spoke French without any accent (if not a Parisian one, in the beginning) and spoke Italian with a slight French accent, having arrived in France at the age of 7 years. Forcibly incorporated into the Italian army during World War II, he deserted to remain faithful to the principles of France. But, although his wife and four children were French, he never wanted to give up Italian citizenship, out of respect for his parents. Despite this, he was ranked 23rd of the 100 greatest Frenchmen, 17 years after his death.

Jack Dancy is clearly struggling with his status as Englishman living in France.