Conflict de Canard

‘Marché’ means ‘market’. ‘Gras’ means ‘fat’. Welcome to the awesome ‘Marché au Gras’—the Ugolino’s Tower of every vegetarian’s worst nightmare, but the Bower of Bliss on my quest to understand authentic French country cooking.

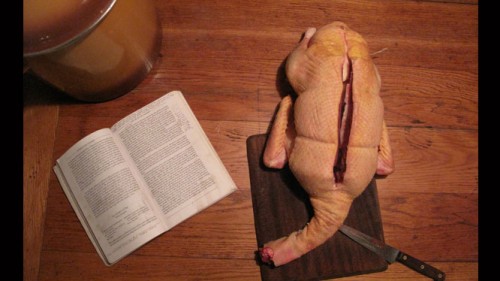

The Marché au Gras is where those of us who aren’t the wives of traditional peasant farmers buy our fattened geese and ducks, to go home and do battle with—about 10 hours of culinary warfare give or take—at the end of which we have enough food to last several months, stored in distinctly unappetising looking jars in the larder.

Picture the unpicturesque scene. It’s a gymnasium on the edge of an unremarkable South-Western French town, 8:50 am on a rainy January Monday morning. Outside firmly-locked doors are a crowd of nervous-looking locals, a policeman with a whistle, and me. 8:59 rolls around. We jostle for position. The clock strikes 9; the copper’s whistle blows; the doors swing open!—and the crowd rushes with more than a hint of elbow-work. And what lies before us is a very strange sight indeed.

Perfect rows of tables are covered with serried ranks of geese and ducks, trussed and plucked, their heads curiously allowed to hang down, and all guarded over loomingly by their owners/pluckers/stuffers. These birds have been stuffed (force-fed) to make their livers huge and tasty for foie gras, and to ready them for the awesome process of rendering into confits, rillettes and other equally delicious treats.

When I first went to these markets, the birds were sold ‘closed’, by which I mean their livers were still inside. Buyers would try to read them like crystal balls to see if the liver was suitably large and yummy, by running their hands over them like pianos, trying to ascertain what lay within. The liver is the expensive bit, and you’re buying sight unseen—a ‘pig in a poke’. Nowadays, the vendors tend to remove the livers and sell them separately, putting a lower ‘open’ price on the birds which are otherwise still entirely unbutchered (i.e. full of unpleasant things). That way, the liver has one price, and the bird another. This year, I passed over the expensive foie gras and bought two ‘tête-rouge’ ducks to make lots of confits, rillettes and magrets. Anyone who’s ever done this before is by now, reading this, quite hungry.

Outside the market, an even stranger crowd sells live poultry to locals with gardens who intend to raise them for eggs or meat. One man sold pigeons, another had quails. At €3 a pop for a quail (pictured) I was tempted to grab a bag full, but it’ll be a far distant Sounder post when I know what to do with a live quail in the kitchen, let alone get it home in my car. Instead I bought eggs off a man who lined his clucking chickens up contendedly on hay beside his car. It was a very un-Tesco like experience.

But seriously, all squeamishness aside, this is the continuation of an astounding culinary tradition, and part of an amazing process. The fattened duck (along with the pig) was in pre-electricity times the fridge, bank account and garbage bin of the farmer. Fresh meat doesn’t last long outside the freezer. By process of salting, smoking and different forms of preserving, these amazing creatures can store enormous numbers of calories, and be transformed by the magical processes of French country cooking into literally months and months of food. Each time I go through the process, I waste less. Everything, from the neck to the giblets, to the bones and the fat gets used. What they say for the pig—that you can eat everything except the squeal—holds true for the goose. Whatever your view on the cruelty or otherwise of the process, you have to marvel at the thriftiness. That alone is a form of respect.

I apologise for the unremarkable photo quality—I was too focused on other things to think camera angle and aperture. But I don’t apologise for the subject matter. And I have a larder full of goodies. If you’re interested in recipes and what really goes into making confit, read Jeanne Strang’s brilliant “Goose Fat & Garlic”.

The Marché au Gras takes place in the winter all over the south west of France, but particularly in the towns plotted on the map below.

Jack Dancy is a trip planner who remains wanted for first degree homicide in the duck community. Anyone with knowledge of his current location should contact Trufflepig immediately.