Defying the Mafia In Palermo

I was in elementary school when the images of magistrate Giovanni Falcone’s car blowing up on its way back from the airport filled every TV-screen in the country. The third instalment of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather had come out just a couple of years prior, but this was not a scene from a movie.

The mafia had decided to take out the symbol in the fight against organized crime, by killing him (together with his wife and three police escort agents) in a spectacular way – with tons of explosives buried under the street that, remotely activated with a control, detonated and ripped the road open.

The death of prosecuting magistrate and judge Giovanni Falcone on May 23, 1992 was not the first nor the last of the long bloodshed carried out by the Sicilian mafia, Cosa Nostra. Just 57 days later, his colleague Paolo Borsellino was targeted, as he was on his way to visit his mother and sister. Today, close to the Palermo promenade, there’s a mural depicting the two magistrates together, painted after a famous photo, commemorating the two victims of the mafia.

Many had died before him, and many would be killed after, including journalists, businessmen, activists, lawyers, politicians, and priests. The reach of Cosa Nostra dates to the 19th century, and its tentacles run deep through society. It would be a mistake to think that the mafia only targets certain categories of people: ‘regular’ citizens are not off the hook either. Cosa Nostra has a way to get to them too, sneakily. If you turn a profit running a business, you must share some of it with them, and they will know if you do or you don’t.

Entrepreneurs and small-business owners are coerced to pay the so-called ‘pizzo’, a percentage on their income as protection money, to the mafia, through intimidation and threats. If shopkeepers won’t submit to this extortion, the message will be delivered louder” and clearer: their shop will likely be vandalized, and they themselves, or a family member, could be hurt. It’s a very well-oiled system, a sort of perverse social custom.

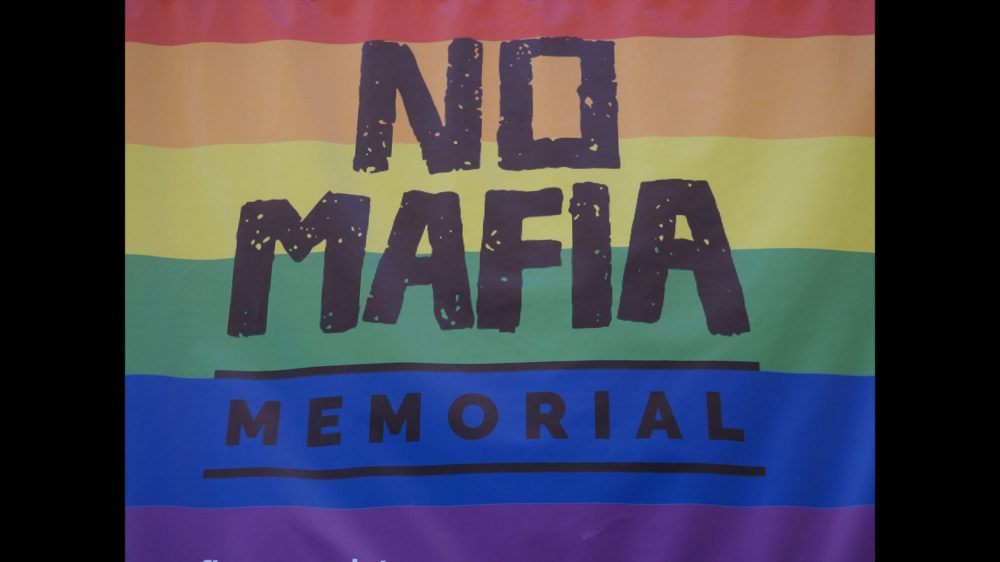

Since the mid 1990s, some associations have taken it upon themselves to stand up to the Mafia, and try to change the situation by promoting social justice, the culture of legality, fighting organized crime and remembering the victims of the mafia. One of them, Libera, organizes outreach activities in mafia strongholds, and summer camps in lands that were formerly in the possession of organized crime.

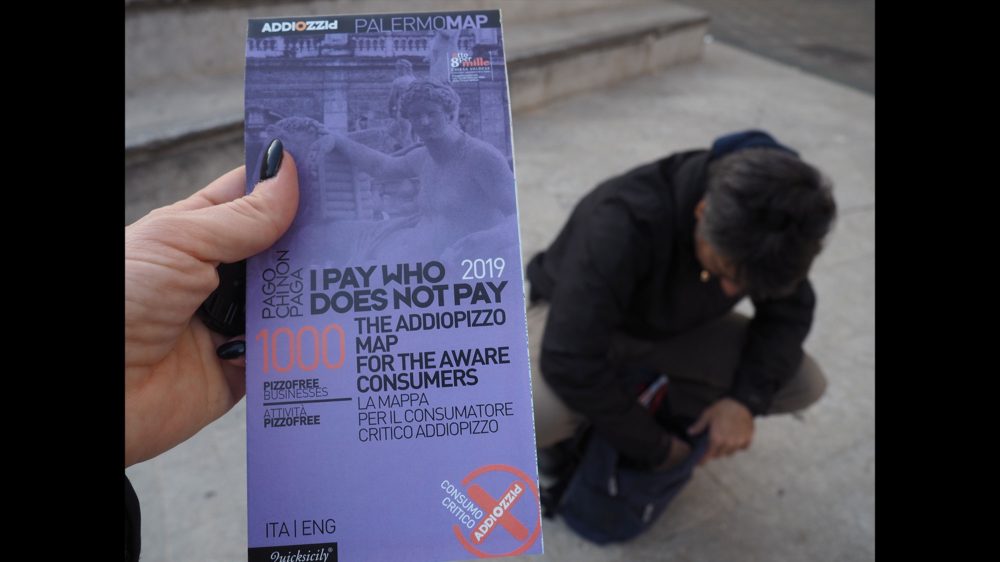

As you stroll through Palermo, you might notice a sticker on some storefronts, with an open circle, an X in the middle, and the words ‘consumo critico’ (critical consumption). This indicates that they’re a part of Addio Pizzo (“Goodbye Protection Money”), a grassroots movement started in 2004 to promote social and cultural awareness, educate people, provide legal and practical support to shop owners in their refusal to pay a cut to the mafia. They’ve created a network in town, to fight the racket.

It was started by a group of people whose youth was marked by the death of anti-mafia personalities, including Libero Grasso, one of the first who refused to pay the pizzo. In January 1991, he wrote an open letter to a local newspaper (Il Giornale di Sicilia) that read:

‘Dear Extortionist, I wanted to warn our unknown extortionist to spare threatening phone calls and the expense of purchasing fuses, bombs and bullets, as we are not available to pay fees and we have placed ourselves under police protection. I built this factory with my own hands, I have been working for a lifetime and I do not intend to shut it down…If we pay the 50 million (lire), they will then come back demanding more money, a monthly fee, and we will be destined to close the shop in no time. This is why we said no to that ‘Anzalone Surveyor’ and we will say no to everyone like him.”

He was killed a few months later, on August 29th of the same year. But his example lived on and has inspired many to defiantly stand up to the mafia and refuse to bow down.

Supporting these local everyday heroes, by shopping at their stores, or eating at their restaurants, is an act of social resistance and civil justice.

Luisa’s background in art, journalism and food helps her plan out regional trips in Italy beyond the usual clichés and viewpoints. Contact her directly to start talking.