“Del rigor en la ciencia”

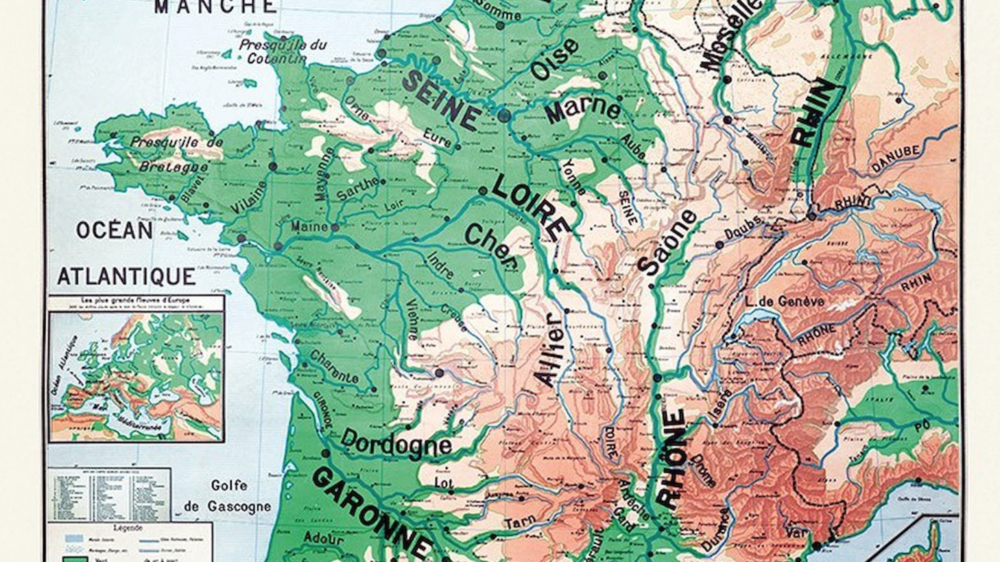

I like maps. I like how they help me understand large swathes of land that I am unable to see with my eyes and feel with my senses. I can picture a planet whole. It’s reduced to a handful of parts, for sure, but a picture is formed that helps in understanding.

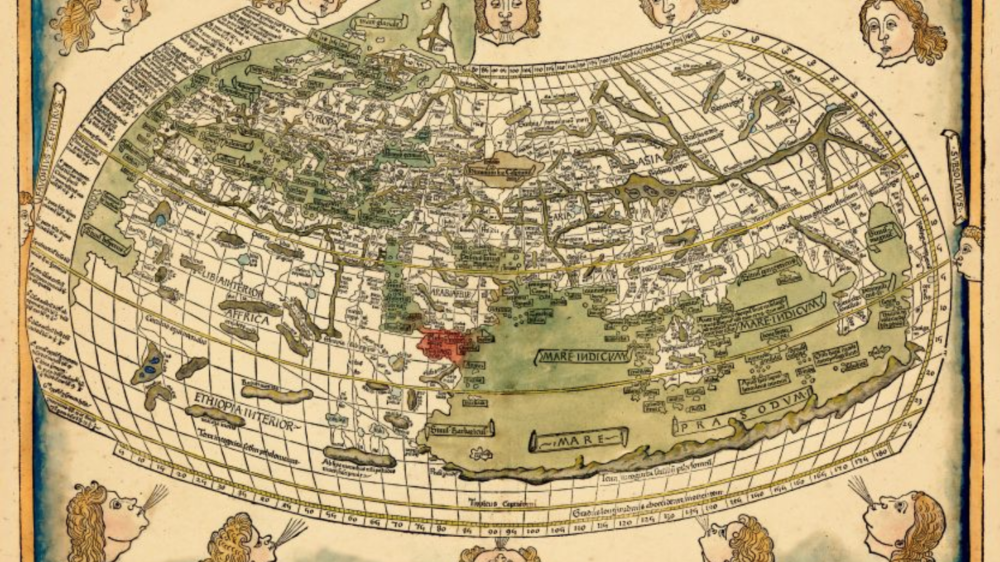

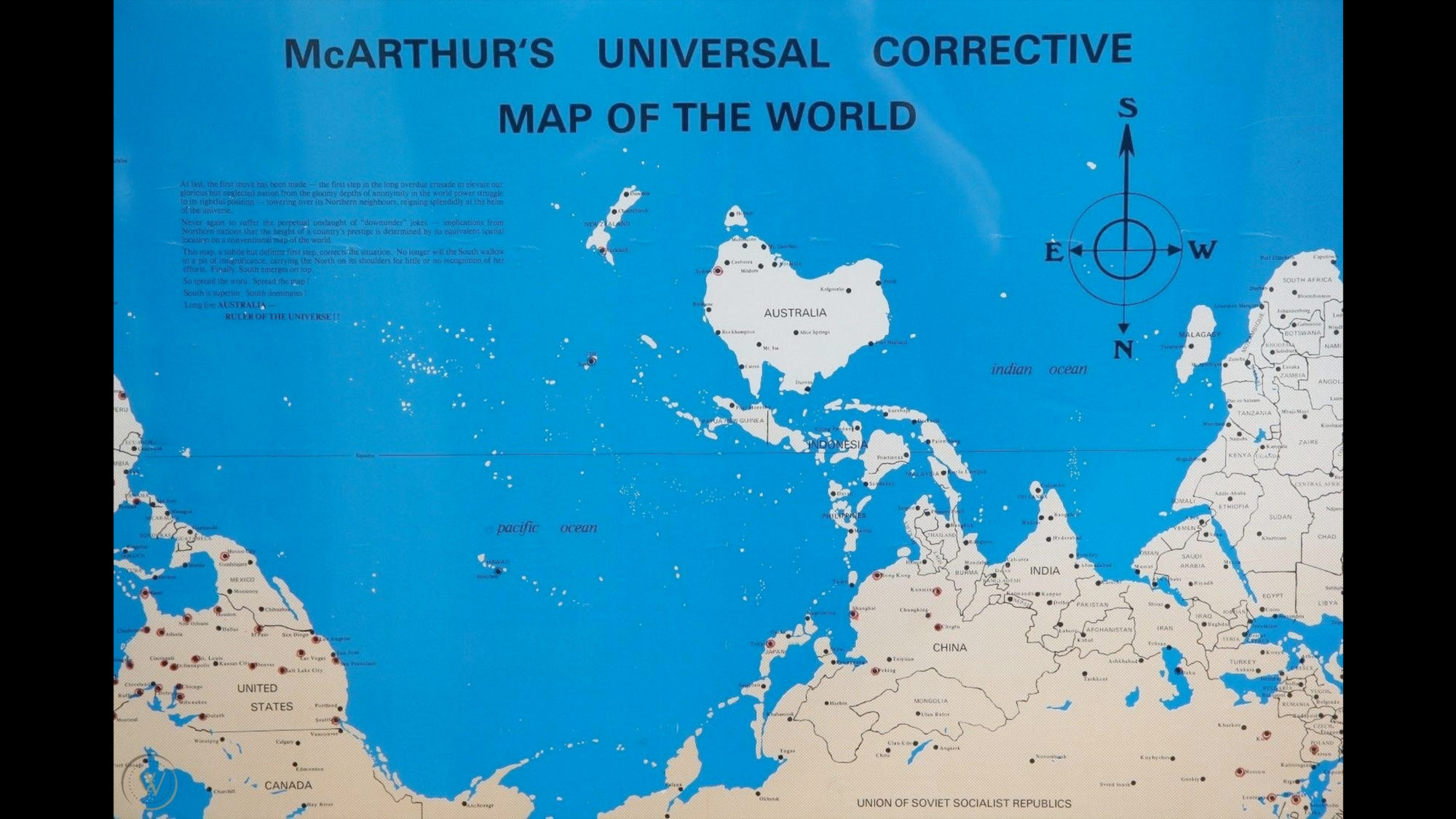

I will never forget learning how to read a map. I mean properly read a map. My uncle Lex taught me one Thanksgiving in Mobile, Alabama. Travel was already in my bloodstream like a junkie, so the maps became my needle and spoon. I collected, and still collect them, good maps, bad maps, fictional maps (which all of them are to some extent). Recently I became obsessed with the distinctions on our globe. Specifically east and west distinctions. In my adult life, these two subjects have been central, the dichotomy of orient and occident, and it has always seemed ridiculous to me because the earth is a globe, spherical, and there is no east or west, top or bottom.

Growing up in the Americas, whenever I heard about the East, the Far East, the Mid-East, it never made much sense to me simply because the flights to the Far East, at least from Athens Georgia, always flew west. It took a long time for me to learn about the geopolitical map-making hierarchy: that Europe was the central point, the church and the bank, and all other points on the globe in relation to this, to Greenwich Mean Time. I learnt that my hometown was not the centre of the world, at least not the way it was taught to me in 6th grade history class.

So I started digging up how these definitions were made, and when, and in what language. Recently I discovered that the defining characteristics of what makes a “continent” are not agreed upon, that the rule I was taught (that there are 7 continents on the planet) was actually a made-up number not agreed upon by science nor politic, and that there are a plethora of definitions and continents depending on whom you ask and where they’re from. From the Russian view there are 6 continents, the UN defines 5, and the tectonic plates give us 15. This was an Earth shatterer. My realm of the forms exploded, my needle and spoon lost, and I was scrambling to find Terra Firma.

To be honest, I never really calmed down after that, and I still am confused that what I thought was a universal truth turns out to be mythos, conjured up from the air at the whim of whomever is asked. I did become more comfortable with understanding that this wasn’t the only thing uncharted and unmoored, that the distinctions we make with the lines on our maps are all created fictions, and that many of the charts we make are there to comfort or sooth but have no footing in the actual. I realized that how I talk about “place” can be something I do on my own terms, that I can name things in a different way and look at my mental map of the place around me with new eyes, that my subjective experience is worth considering. Travel helps me do this: it makes the maps full scale in living colour. I still love my old maps, and perhaps appreciate them more, for the fictions that they are. And I am still unsure where the East meets the West. Looking at maps, conceptualizing space and time, something happens, something I don’t know, but it sure feels like magic.