Gilded Splinters

As a kid growing up in the South, you hear a lot about the Civil War. I was told stories of Generals, of Robert E Lee, a well rehearsed account of what happened, from one particular point of view, the white south. I was seldom taught the history outside of this perspective, it was either of the white south from the southerner, or of the white USA through the colonists eyes, or the revolutionaries eyes, rare was the south told from the enslaved, if it was there it was a sanitary Disney version, quaint, supporting role, but far from real, landed squarely in cartoonish fiction.

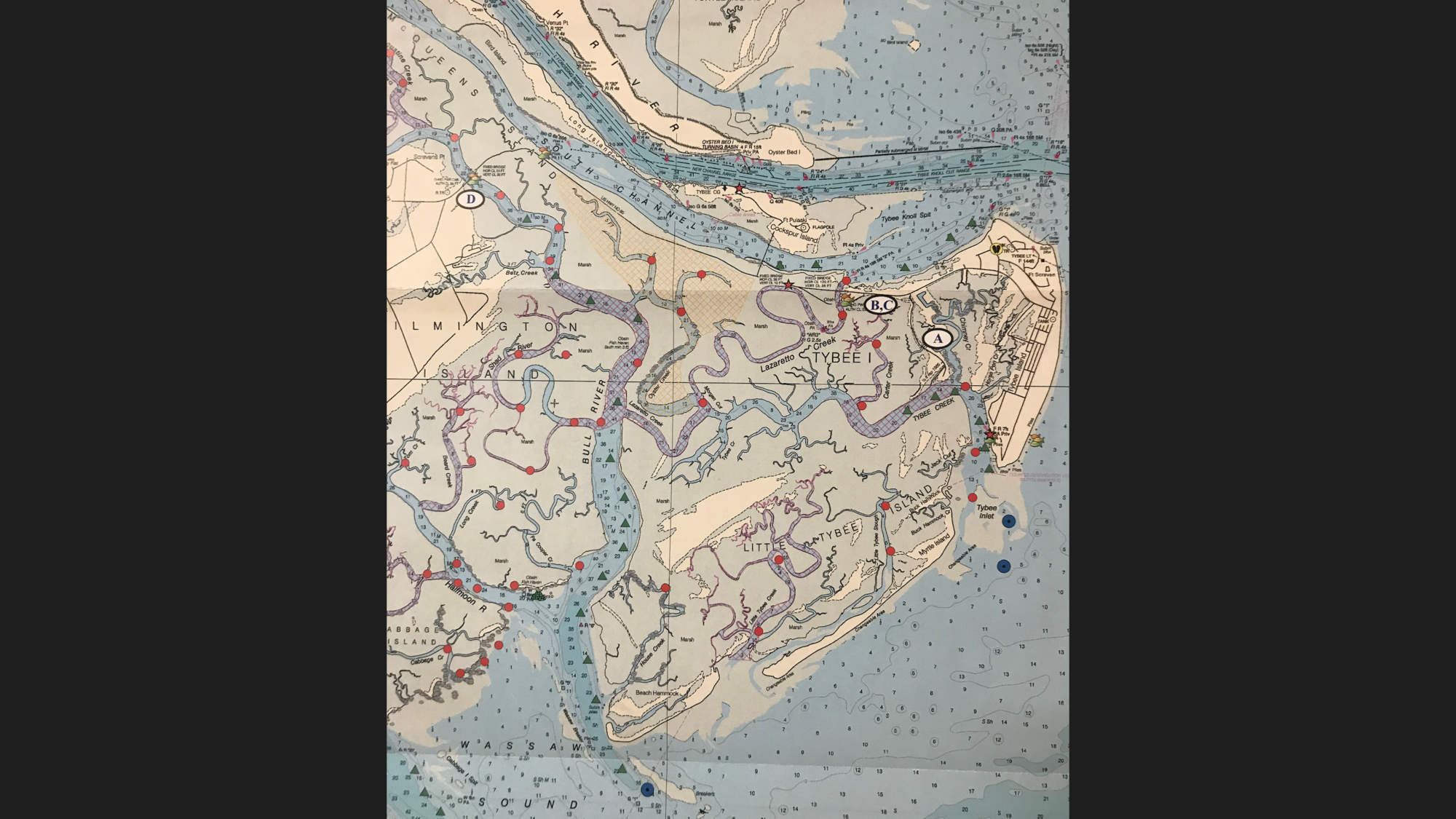

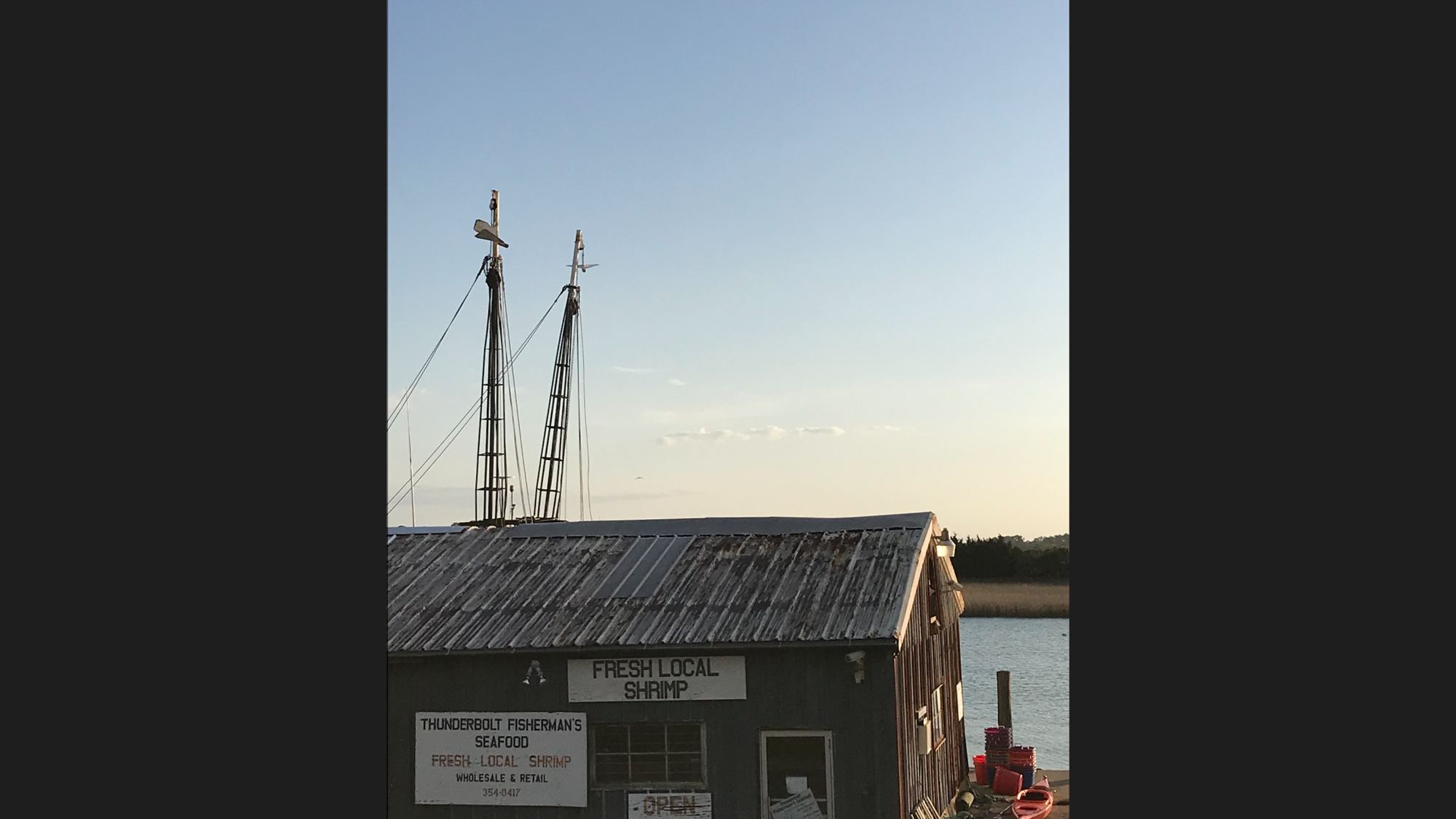

I work in travel, and in order to understand the subjective and objective of a place, I go on the road to look, to feel, to experience. Last Spring I went back to the south. My research trip was to start in Savannah after visiting family (I grew up in Georgia), then head north up the coast by boat and road, through Beaufort, ending in Charleston. This area is called the low country.

Something else was happening when I was a kid in the south. A new hunger for land and resources was starting to mature. Lumber was already big business there, pines specifically. And as the world grew, and buildings rose, the need for natural resources grew greater. China was hungry for wood, Europe, North America alike, and pines grew tall and straight in the low country. Populations were growing and vacations were needed. And the low country supplied both of these needs, vacation spots and tourism economies, as well as lumber on the low country islands. Developments like Hilton Head Island were springing up, large companies investing in golf courses and housing projects on the rural barrier islands long forgotten. The problem was and is, this land was given to a population of people who had been enslaved by the landowners in the 1800’s, the land had been given to the Gullah Geechee. The glorious 5 star resorts I was interacting with were waging certain land battles with small communities of Gullah Geechee, because the once malaria ridden landscape was not paradise, the change being perspective and market economies.

It matters who owns what. It matters who owns what because it shapes places, how we interact, what we remember, and why. Understanding why someone owns what, the motivations, shapes how it fits in the place, in the community. This is important because communities, groups of people, and their ideas and ways of life, are particular mental maps for knowing. Our own individual world is just one of many, a model of reality. Through understanding culture and language we can understand new realities.

The low country is a space of salt marsh islands between Charleston South Carolina and the Georgia/Florida border. It is tidal, it is in motion. There are islands that become part of the mainland at certain times of day, you must consult the tide charts to know, affected by the pull of the large moon orbiting our planet, pulled towards its mass, the rivers and oceans swell and make those salt flats fill with water twice a day. It is in this landscape that the pre-columbian people thrived on grains and fish of this region. There were a number of groups who were distinct from the tribes that were 20 miles inland, the Kiawah as opposed to the Chicasaw and Cherokee. English colonists came and settled in the protected inlets and river mouth bays of places like Charleston and Savannah, on bluffs raised above the tide. Rice was the business to start, and to fuel that business a transportation triangle was formed with west Africans stolen and sold from Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Benin, Togo, and Nigeria, brought to the Caribbean and south east Atlantic coast of the USA, forced to farm rice which was then traded with cod and rum, and transported to the United Kingdom, which in turn sent the ships to West Africa; over and over and over again, displacing generations of humans, stolen lives.

Thus began a dynamic that shaped North American culture and politics since. It was realized that cotton grew well in the tidal low country, and tobacco, so more labor was wanted to run the industry, more lives interrupted and stolen, more product, more profit, more production. It is an old story, a story of capital, the endless hunt for cheap labour. Cotton eventually was found to be sourced in other places, the Civil War changed laws, and the low country changed, but before that it created a large economy which built the old cities of the south. With the money and industry that came out of this, came power, and with power a divide, a North and a South. This division was early on in the politic of the United States, it is why Washington DC straddles lines into Virgina, why New York still holds a bitter taste in the mouths of certain generations of southerners. The growing bank accounts of the Southern aristocracy allowed for the idea of succession to enter the room, and the South wanted to step away from the whole. The North didn’t want this, nor like this, and a civil war was to begin. On April 12, 1861, at 4:30am, the fighting began with an attack of Fort Sumter, a small island fort in the mouth of Charleston harbor, with Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard ordering fire onto his old West Point professor Major Robert Anderson who was inside of the fort.

Seven months later, the Union navy bombarded Port Royal, just south of Charleston (what was to be called Hilton Head Island later). The Union navy and army sacked the island and moved inland, taking Beaufort SC and St Helena island. As this navy moved in, plantation owners fled leaving the enslaved and indentured behind. The Union Army decided to do two things in this situation, give the land to the now freed slaves, and pay to harvest the highly valuable cotton ready to be shipped. This was not purely out of kindness and humanity, this was to have the monies secured from the cotton harvest, a large sum the Union was keen to keep. The land was given to communities and families and things began to shift for the people. Towns began to grow, and a way of life thrived.

Then, Lincoln was shot and ownership shifted again. The promises made by those in power evaporated, the plantation owners returned, and land was handed back out of the hands of the new communities. Some were given other land, and some were able to keep the land they had, and a fracture was created between a community and a government, a logical distrust.

How we relate to property and ownership is a cultural value, it is indoctrinated through legal processes, but ultimately it is a belief system, an idea, a philosophy. The concept of land ownership in the Gullah community was different from the plantation owners who were writing the laws of the state. This difference continues. When a family member died, the ownership was passed down through word of mouth and divided into a family, rather than through lawyers and wills and the state, it was local, communal understandings. There is a distrust of the state, naturally after being lied to. In South Carolina legal parlance this process is called “Heirs Property” and is a swiss cheese legal standing that allows anyone to come in and purchase land that has belonged to generations at any given time.

Currently, property that was given to one family in the 1860’s, has been handed down to heirs so many times it is now a percentage pie of ownership spread out between cousins and distant relatives. In South Carolina law, if any one of these small percentage owners is interested in selling their .05% of a chunk of land, the entire 100% of the land has to go up for sale. Post Civil war south was not the friendliest place for newly freed slaves, so there was a large diaspora that happened creating large communities in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, California, etc. Years later there are people who have no connection with the sea islands, finding out they are percentage owners of a small tract of land in South Carolina, and are sought out by development companies looking to build resort communities. You can see how this distant relative might be interested to sell a piece of land they have no connection with seemingly. If they express interest in selling, the legal mechanism kicks in, and the entire property must be put up for auction. On paper, this means the people living on the property, who grew up there, have the opportunity to buy back their land, but the property value has risen to a point that is unattainable, $800,000 per acre, high stakes real estate. This is one of the two ways land can be taken from this community.

The other way is through tax evasion. Remember the division of the property from multiple generations, property tax is divided as well, and if one slice of the property is delinquent, then the entire property goes up for auction.

These two processes left wide open for any real estate speculation, allows for land, land that was the first land given to those who had been enslaved in the United States of America, the first place in the south where an african american was paid for their work, this land can be taken with no or little protection from these communities. This isn’t ancient history, this is happening now. Island resorts are still being built up, still being worked on, and in many instances the new real estate projects are named “Plantation” or “Plantation Club”

This is where it ties back into tourism, this is where it ties back to my job. I was back on this coast, searching and learning about histories I never learned about when I was a child, and I was finding that some of these places are still locked into a fissure, a broken promise, the contradiction at the center of “the American Dream”.

History always has a solid mixture of fiction and reality; depending on who writes it, folklore and mythology woven with science and fact. It is full of contradictions and must be sifted through. And here in the Low country, where some of the oldest post-columbian history lives in the US, there are trends in the stories often told. There are the American Revolution stories, the civil war stories, great depression and prohibition stories, and civil rights stories. Some of the stories have been lost, and are being found, those are some of things I go out looking for when on research. The Penn Center, just outside of Beaufort, part of the US National park service and a National Historic Landmark District, is the site of the first school founded in the Southern United States specifically for the education of African Americans in 1862. It was also a place of gathering during the civil rights movement with Martin Luther King Jr., and it is currently a culture center for the Gullah-Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. It is also a gathering place for legal reinforcements in the chess-like land battles happening in South Carolina due to Heirs property laws and property tax issues. Stated on the Penn Center Website:

“To combat the threat of rapid commercial development and land loss along the Gullah Geechee coastal communities, the Penn Center led to the institutionalization of one very important component of community sustainability—land ownership and retention.”

The center established the Land Use and Environmental Education (LUEE) Program to assist islanders with issues of land retention and stewardship through education and legal services.

Knowing context helps one make decisions, and when we travel, we are given the opportunity of choice. Choice to listen to the stories, choice to seek out context and knowledge, choice in where we go, how we go, and why we go. The stories we tell about a place affect how a place functions, and as travelers and tourists, it would be neglectful to not try to understand context, stories, history, and the layered realities of places we visit. The untold stories of the American south are starting to resurface, and this is not accidental, this takes seeking them out, a digging.

In Charleston, where the Cooper river empties into Charleston Bay, there is an old jetty and a park called Liberty Square, but it used to be called Gadsden’s Wharf, and it was the largest slave port in the US. It is estimated that over 40% of those stolen souls arrived in this wharf to be brought a few blocks away to a human market where they were sold. Next to the park is a ferry tourists take to get out to the island Fort Sumter marking the first shots fired in the Civil War. Over the past few years, construction has been keeping this area busy as a large building is being erected next to the park, the International African American Museum. This is a big project, and will be a harbor for the lost stories of the American south, but not just that, it is the international museum, so it will be a depot of the stories from Newfoundland to Benin. It is in places like what this museum will be, and places like the Penn Center, we must seek out the stories not told in the classrooms of late. It makes for better travel, better history, and better community. And when you follow the threads these stories weave, it leads you to places like Ghana, Newfoundland, and Charleston. Letting curiosity lead our choices rather than an advertisement campaign or algorithm will make all the difference. In the next few months the International African American museum will open, and I intend to be there to hear all the stories I can.