Greek music: beyond Zorba

I am trying to recall my first introduction to Greek music. I was a teen when my parents took me on holidays to the island of Corfu. Was it during the taxi ride to the hotel – taxi drivers love their music, and they like it loud – or was it that night we signed up for the (cringe worthy) ‘village experience’, a dinner under the stars with traditional dances performed for us and at least five tour-bus loads of tourists? Either way, it didn’t sit well with me, and the decision that Greek music is “not cool” was swiftly taken.

Fast forward a decade, my heart lost to a Greek man, summers (and eventually most of the year) spent in Greece. Heavily prejudiced by my own teenage opinion I stubbornly stick with my decision to not like Greek music. Except, there are these evenings of gatherings with friends where instruments are picked up and the singing starts. I am not singing along, but I am starting to move to the rhythm, and I feel the emotions wash over me. Damn, I am getting it! Even if a good part of the lyrics are lost on me, I sense the joy, sadness, love, loss, struggle, celebration and hardship in the gripping melodies.

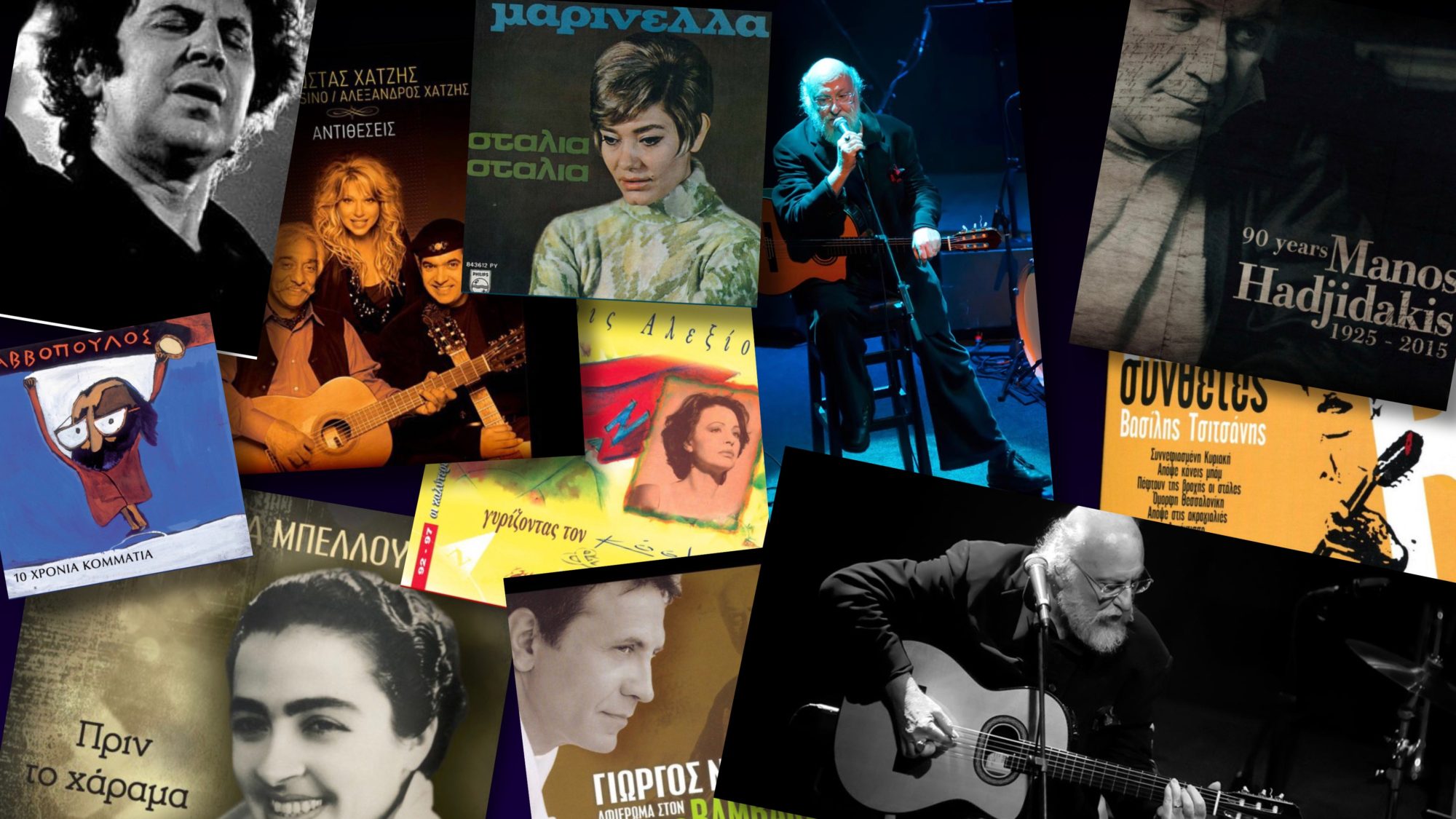

I dive into the CDs we have at home. Kostas Chatzis, the gypsy with his guitar, singing his heart out. Mikis Theodorakis, the grand master of contemporary Greek music, known internationally for his movie scores (remember Anthony Quinn “Zorba’s dance”, yes, that’s his). How lucky was I to see him perform, aged 80-something, at the magnificent ancient Herodion theatre. Manos Hatjidakis, the other giant, famous for his melancholic melodies, oh, and the Oscar he won for “Ta Pedia tou Pirea”, the theme song of “Never on Sunday”. And Dionysis Savvopoulos, singsong writer, poet, troubadour from the sixties, still active. My, if there was only one Greek artist I was allowed to listen to for the rest of my life, I’d pick him in a heartbeat.

Then I start digging deeper. The oldest folk songs, still played at village celebrations, and a bit of an acquired taste. The neo kyma, the “new wave” of songs that took hold after the 1960s – romantic, often just a voice with a guitar. The Greek rock scene of the 1980s and 1990s, blending Greek traditional music with the sound of rock music of the time. The more recent popular songs (ta laika) blaring out of the radios of taxi drivers (I still cannot get hooked to those). Even the strangely enthralling anthems of today’s mega-popular singers whose lyrics Greek youth repeat in a trance in capacity-filled stadium live performances.

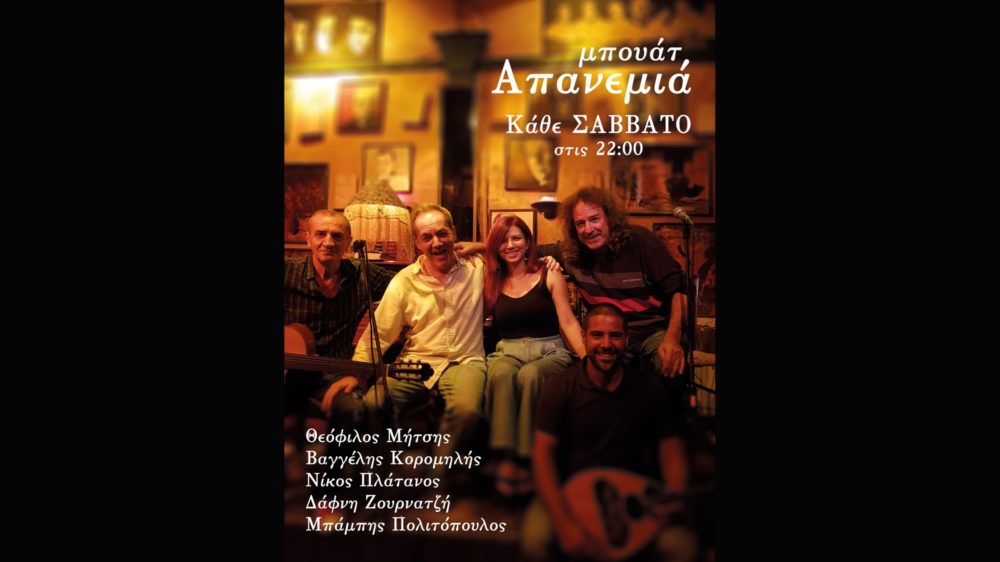

Most fascinating I find Rebetiko, the 1920s music of the Greek refugees from Asia Minor, also known as the Greek Blues. Haunting pieces, composed by musicians living at the margins of society, music of the underworld, ports, prisons. Music that went through a revival during the Junta years (1967-74) when the military dictators prohibited the songs for being subversive, a ban that only helped the genre become more popular, and indeed it has since become an intrinsic part of Greek culture. There are evenings at rebetadika, where the music doesn’t start before ten (and won’t stop until shortly before sunrise), the alcohol flows generously, and plates with mezedes keep me going, albeit not as long as the locals.

And so it has happened. Greek music has become part of my life. I will keep exploring, learning and loving the variety of styles, songs and voices. I have made my first playlist. A few classics (but not the ones you probably know) mixed with some personal favorites. Enjoy.

Jacoline’s new found love of Greek music is thanks to years of rakomelo drinking lessons from local friends. She keeps her bouzouki well tuned and strums up fantastically piggy Greece trips. Get in touch with her to get planning.