Light Fuse Get Away

August 24th 2008, the day after my 29th birthday, my mind was tattooed with an image. It was the closing ceremony of the Summer Olympics in Beijing and I had spent the past 30 days guiding a family all over China, intermixed with gold medal event tickets for the two weeks of the games. It was a country on pause, held; the Olympics do that to a place. It is a singular sort of event. There are issues with the Games: corruption, graft – but there is a beauty to them as well. We all agree to the rules of a handful of sports and games, and come together and compete, like children, because humans love to play and compete and strut. China was strutting, and the lead up to this event was madness, with construction going on for years, and the setting up of the whole of a country as a stage, part fiction, to be viewed. It was a magical month to be moving around that country seeing it in this state. And to end it all, the closing ceremonies.

That night the heavens opened up with fire and brimstone in a display of pyrotechnics I had never imagined could be possible outside a war. The sky was on fire, and it was beautiful. Five simultaneous fireworks shows were setting off across the city of Beijing. I cried, not tears of fear, nor joy, I’m not really sure what, but I cried like I was mourning the death of a friend. This is also a side effect of guiding a long trip. It is the same feeling you get when watching a jet go supersonic in an airshow. Sublime? The memory stuck and it ruined any fireworks I have seen since.

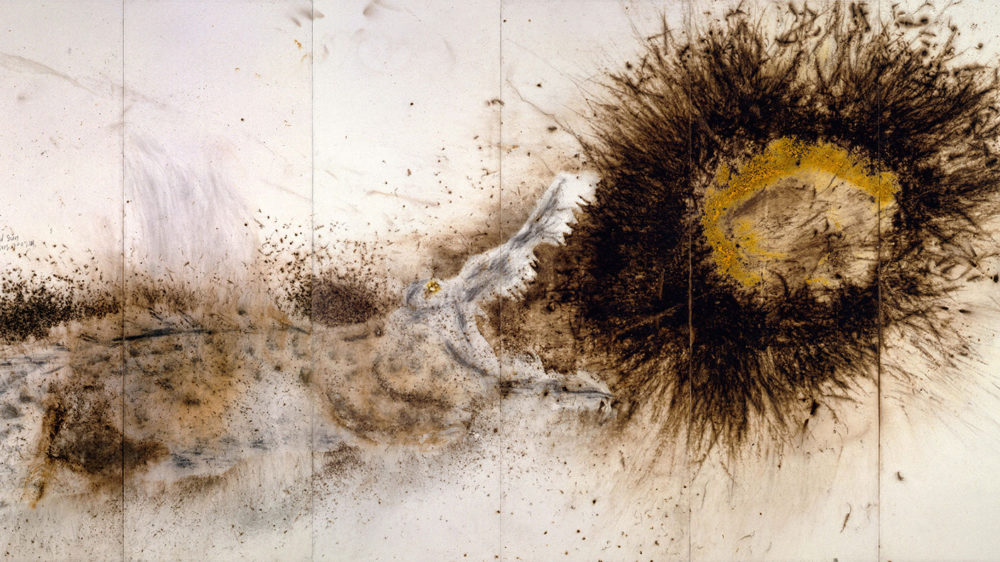

Recently I was covid-doom-scrolling through Netflix and saw a documentary film on a Chinese artist named Cai Guo-Qiang called “Skyladder”. I clicked and I watched. It was then that I understood what I saw in Beijing had been an art form birthed from the mind of one artist, not some collective feat of explosion. Cai Guo-Qiang was born in Fujian Province, China. An artist whose medium is fire and flame. It isn’t a firework show with him, since that implies a chaotic passiveness. With Cai Guo-Qiang it is a deliberate setting of explosions, experimented and tried and designed, mixed with the uncontrollable weather and climate. It is like graffiti in the air, controlled at the outset but at the mercy of the elements. That might be why I cried that night – you could tell it was an expression from some sentient being, some individual with an idea and a dream.

Six years before those summer Olympics, I had moved to China. It was a Tuesday. I remember that because I was due to start teaching English at an International School in Guangdong Province on Wednesday morning, and thus begin my short career as an international school teacher. I was in my early 20’s, very early, a bit too early to be honest, and I had landed the day before in Hong Kong after spending a month in Taiwan, 2 months living in a tent in New Zealand, and years finishing up my B.A. in Philosophy at the University of Georgia, a very long driveway to a strange new home.

Hong Kong had been brilliant. The school put me up in a hotel while my VISA was being worked out and even sent an employee of the school to buy me dinner and get me some things to prepare me for a year teaching. I was impressed with Hong Kong, with its modern feel, its organizations. Cute little road signs, perfectly sized taxis, trains that ran on time. When we left, we boarded the train on the old route from Hong Kong to Canton (now Guangzhou) and I quickly fell asleep.

It had been a fast few weeks and I was exhausted. I had been loosely trying to get work teaching English to fuel surfing and the late nights we all have in our 20’s. Somewhere along the way, I had posted my resume on “Dave’s ESL Café” website, a site famed for being a central website supplying teachers with schools. I was hired the folks foolish enough to take me were a new school in Mainland China. They were just starting up, having opened that same year with 3 students taking classes. Now they were expanding and needed teachers fast, so the Principal found my resume and called me. He needed teachers, fast, so he said I had an hour to think about it, and being young, foolish and overly confident, I thought for about 10 minutes and then said yes! They booked tickets, told me where to be and when, and off I went, into mainland China in 2002, knowing absolutely nothing about the place.

When I woke up the train was slowing to a crawl as well as creaking loudly, owing to its going from British rails to Chinese ones, and we were leaving the Hong Kong Territory and entering into the People’s Republic of China. It was a particular crossing: at the time, that was one of those crossing where you feel politics and wealth change along with the landscape. It’s what I imagine East and West Germany felt like, and what you see in so many Cold War spy movies: barbed wire, towers, guards, piles of wood and rubble… lots and lots of rubble. We were crossing the Sham Chun River into Shenzhen, which was a place that was developing faster than any other region in the world had ever done, due to its tax exemption as a Special Economic Zone (thanks to Deng Xiaoping).

At that moment, crossing the river, waking up after the haze of the past few weeks, I felt fear. I saw the barbed wire and rubble and construction, and I was terrified that I had made a mistake in taking this job and jumping into a place I knew nothing about. I could not speak Mandarin nor read it, I did not know the culture or history, I had no idea where I was on the map, and I had landed in one of the fastest, largest shifts that the world has known to date: China rising.

It was one of those sea changes in a lifetime, crossing that bridge. And that fear I felt had everything to do with it. I was jumping into a place that was unknown, exciting and intimidating, that same feeling we chase each time we head to the airport or train station.

I spent 7 years living there and over two decades working in China. It was an entire world that I had not known, one that was filled with variety. A history written in different ink.

These two memories both have a thread that connects: the value of discomfort. I was uncomfortable when I moved to China and I was scared. I didn’t understand. It was the same with the closing ceremonies: there was a feeling I followed, but did not understand, an uncomfortable sublime, a subconscious wall that one must break through for growth. It is something I think about a lot in planning travel, the value in these experiences and how to understand that sublime fear and discomfort, for when we all leave the zone of comfort is when we are really traveling.