Peak Performance in the Azores

Some 500 years ago when the Portuguese began settling Pico island in the Azores, nobles, merchants and farmers found rocky, inhospitable terrain that nonetheless was rich in the typical nutrients found wherever one finds volcanoes. Olive and wheat production was initially a failure, so this shifted to growing timber, vines, and fruit trees. If you’re going to survive in the ass end of nowhere, you need to arm yourself with good wines, fruits for eating (and making moonshine) and timber to build the lightening fast ships that would make up the Azores’ famed whaling industry. Turns out phylloxera had other plans for Pico’s vineyards (but not before Pico wines crisscrossed the Atlantic for centuries, ending up on the tables of US presidents and Russian Tsars alike), and whaling eventually was abolished (astonishingly, barely 30 years ago).

I’m reflecting on this enigmatic volcanic island’s history on a picnic bench looking out to the Atlantic with a plate of grilled lapas (limpets, cooked in wine and enough garlic to stop an army of vampires), and a glass of Arinto do Açores variety Pico white wine, as a SATA plane flies overhead to Ponta Delgada. I should’ve been on that plane, along with my other travel industry colleagues on a tourism board sponsored visit of Pico, but what can I say, my interest was “piqued” by the island so ditched my return flight home to spend a few more nights to dig deeper.

The Azores Wine Company, the Pico outpost of Portugal’s rock star enologist Antonio Maçanita, has led the charge to restore Pico wines back to something of their former glory, bringing in the last few years, a state of the art winery and wine making machinery to the island. Rather than seeing them as competitors, they’ve mentored and encouraged a new generation of Pico’s youthful winemakers, many who’ve apprenticed at AWC. The best known of them is arguably the author of the wine that brilliantly paired with my limpets, Lucas Lopes Amaral. He began making wine at Antonio’s estate barely old enough to shave at 19, and has quickly risen since Covid to having his own facilities and harvests from his family’s plots, knocking out characterful wines expressive of Pico’s unique volcanic terroir, winning numerous accolades.

Pico winemaking has never been an easy affair – the first vintners, faced with rich but scarce soils dominated by lots and lots of lava rock, built up an extensive network of stone walls to demarcate parcel ownership which had the added benefit of sheltering the untrellised vines from its greatest enemies, extreme winds and nearby ocean mists that pummel the island. When UNESCO recognized Pico’s vineyard heritage status in 2004, they determined the stone walls so extensive that put end to end, would circle the earth at the Equator, twice. Pico wines were once some of the most valued in the world, and its location in the middle of the Atlantic was a boon for the industry at a time when British merchants bought more than half of the island’s common wine production destined for the colonies, rather than risk spoilage from wines that would start their journey from the old continent. These facts of Pico’s history are all being related to me in fascinating detail by one of the island’s wine sages I have the chance to sit down with, Fortunato Garcia, who holds the mantle of Czar vineyards, producing to this day, the rarest of rare Pico vinho licoroso, a wine pressed from late harvests that achieves an incredible 20% alcohol without fortification but who might at best have two well rounded harvests in a decade.

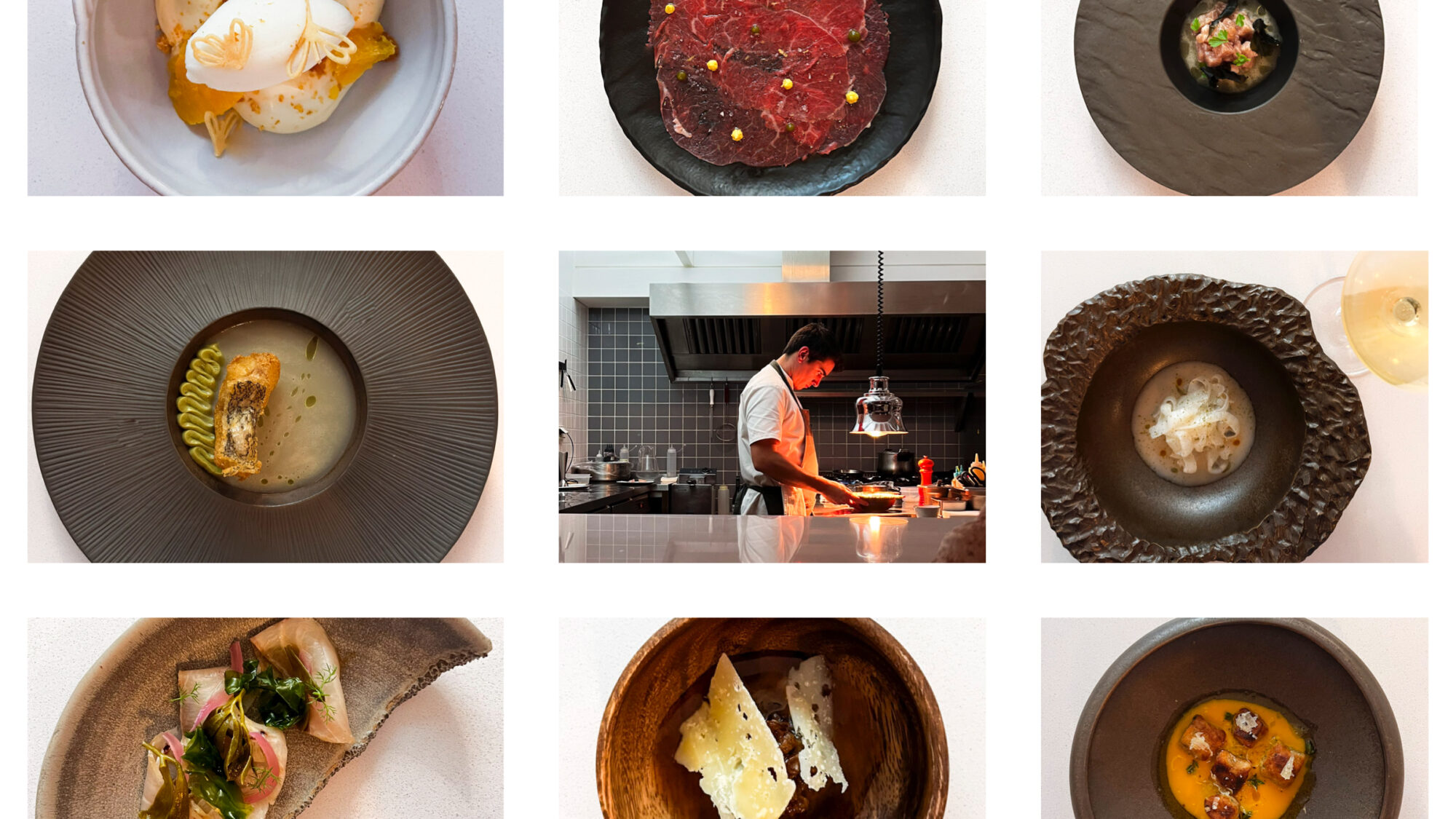

A spontaneous decision to drive over to the south of the island to see the whaling museum at Lajes produces my favourite discovery of this outing, Bioma restaurant helmed by two young chefs, a native from Pico and an Argentinian who worked together in kitchens internationally and decided to pursue the gutsy dream of owning their own restaurant in this isolated Atlantic outpost. It’s a bold move to start up a gastronomic restaurant focused on local product out in the middle of nowhere, when the island relies heavily on food imported from the mainland, the result of a questionable policy in the 80s and 90s to subsidize cattle production and clearing farmland for grazing over encouraging sustainability and self-sustenance. “We regularly visit locals around the island, looking for people who’ve got their own vegetable patches and orchards, knocking on doors, asking to source for our local ingredients,” Rafael, the Pico born chef tells me. Over a fabulous chef’s table tasting menu I learn about the culinary history of the island, from plants and herbs forged for centuries by local families to quirky fish varieties many of which the pair dive and fish for themselves, such as Forkbeard or peixão (Seabream). They’re the first to get authorization to sacrifice and age Azorean beef on Pico for their restaurant. Practically all of the Azores’ prized prime cuts are exported to the mainland.

The Ilha Preta (Black Island in Portuguese as Pico is known poetically) is the youngest of the Azorean islands and its Picarotos (the slang for its inhabitants) are a people with mettle, as Herman Melville observed in Moby Dick referring to the Azorean whalers as the “hardy peasants from these rocky shores” who made the best whale men. It’s thanks perhaps to centuries of isolation and tough living conditions that produces a people with innate willingness to take risks, whether with whales or gathering rocks at the foot of a volcano to coax vines from the soil, or taking a gastronomic gamble in a place most would be hard pressed to locate on a map. Pico is an exhilarating destination for a curious traveler that promises to make a bigger splash in the future.

Call him Ishmael. Call him Sebastian. But call him, or drop him a line to get crafting your Azorean adventure.