Sisters of Fate – A Fado Playlist

As I’ve been writing this post, Portugal has been commemorating a special anniversary: the 100th anniversary of Amália Rodrigues. Her name may not mean much outside Portuguese-speaking circles, but here she is revered as the “Queen of Fado”, and her birthday is an appropriate time for me to confess: I am a die-hard fan of this music. Let me tell you why.

First a bit of history. In 1807, the Portuguese monarchy hightailed it to Brazil to escape the imminent invasion by Napoleon’s forces. There they established their royal court in Rio de Janeiro, to create a “co-kingdom”, and in doing so they fuelled a rise in the import of slaves from Africa, and the subsequent stratification of Brazilian society. When at last the Portuguese monarchy went home in 1821, immigrants followed, and thereby brought the rhythms of Africa with them to Lisbon.

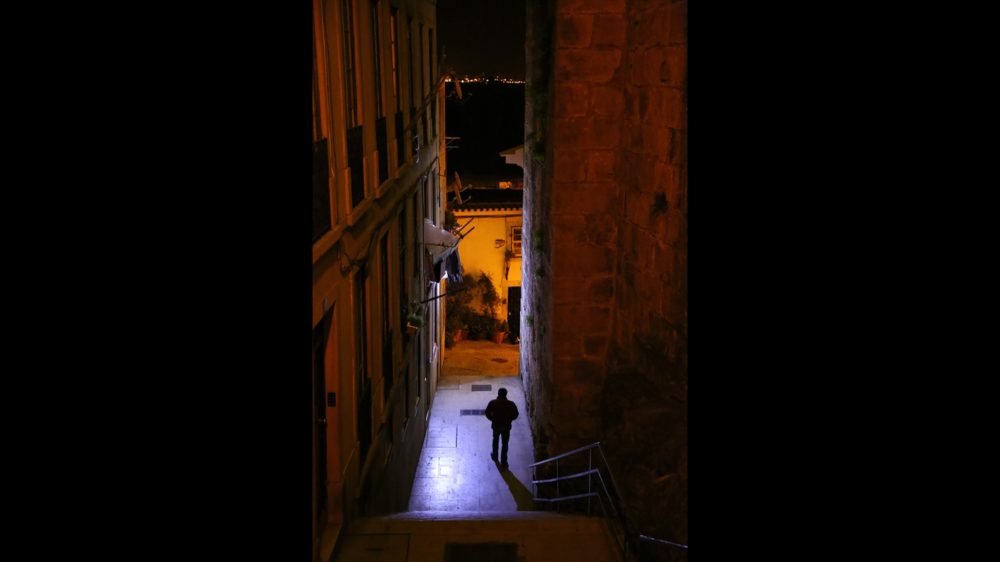

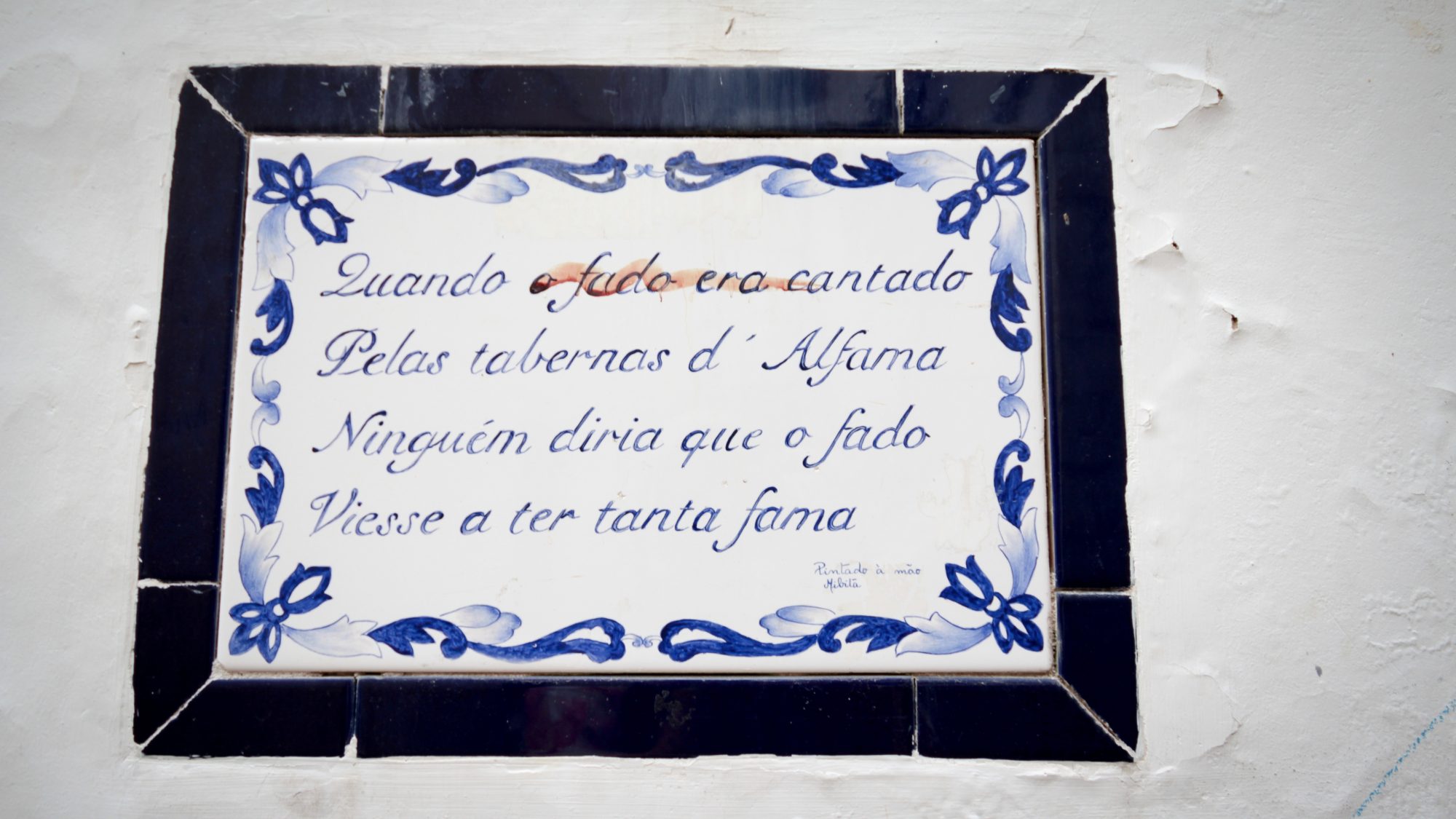

In the ensuing cultural melting pot, Fado was forged on the streets of the popular and racially-mixed Mouraria and Alfama neighbourhoods of Lisbon, and it was the music of sailors, of prostitutes, and of the poor. Fado’s origins are widely attributed to a singer by the name of Maria Severa Onofriana who, singing in local taverns in the 1830’s and 40’s, won favour and suitors among the local nobility, thanks to this new musical style and to her grace and beauty. She died impoverished of tuberculosis at the tender age of 26, but not before securing her place in Portuguese folklore.

So what is Fado? The word translates roughly to “fate” or “destiny”. It’s a melancholic music, usually performed by a singer and two guitarists, with verses that speak of nostalgia and of a yearning for that which is unattainable. The best Fado expresses a difficult to translate word, “saudade”. Saudade might be best described as that bittersweet sense of joyous grief. Saudade is “the sorrow of not having enjoyed that which was there to be enjoyed” (thanks to Richard Elliot for the quote, from his book ‘Fado and the Place of Longing‘).

Amália, born 99 years after Maria Severa, with her impressive vocal range and long career, is to Fado music what Edith Piaf is to French music. To this day she commands a reverence in the wider Portuguese-speaking world that recalls to me the fame Oum Kalthoum maintains in popular Arabic culture. Amália composed some of her lyrics, borrowed from influences outside of Portugal, and internationalized Fado. Even now not a single artist sings in a tavern in Lisbon without at least one song by Amália in their repertoire. On her death in 1999, the government declared three days of mourning.

That said, my love for this music does roll a few eyes among Portuguese friends. It is sometimes derided as being “for the tourists”, or for the older generation. It also brings up negative associations with the Salazar dictatorship, which decreed “Fado, Futbol & Fátima” as the state sanctioned pastimes (Fátima representing the Catholic church). Salazar and the Estado Novo airbrushed away Fado’s working class roots and used it as a tool, censuring lyrics and Fadistas it didn’t like, twisting the music to promote Catholic, Fascist and Nationalist values – hard stigmas to shake. Furthermore, it can be a real minefield today to find good, authentic Fado even in Lisbon, with the result that many persist in writing it off.

But the musical culture continues in the footsteps of Amália Rodrigues. In the past two decades a younger generation in Portugal has stepped in to fill the gap left since Amália passed away in 1999, artists such as Carminho (herself the daughter of musicians), or the Mozambique-born Mariza, who is regarded as Amália’s successor. Many Fado singers tour internationally, and many are recording with artists from the Portuguese diaspora in Latin America and Africa, to bring a freshness to the genre.

Since I’ve been planning Portugal trips and exploring its musical culture, what I’ve loved about delving into Novo Fado is the cross-over with musicians from the former colonies such as Brazil, Angola, Cabo Verde or Mozambique. Internet-savvy Portuguese millennials are embracing Fado and I’ve loved following some of them on social media, like Ana Moura with her husky voice making pasta on her Instagram (this really should go viral), or this amazing quarantine zoom duet between a couple of up-and-coming Fadistas who are regulars in the tavern circuit in Lisbon.

When I listen to this music it still gives me the goosebumps, even while not understanding all of the lyrics. The passionate trills and melismas, and sorrowful chord progressions nonetheless convey sentiments of longing, anticipation, and loss, all of which strikes close to home in the times we are living in. My ongoing search for great musicians around the globe persuades me that music cuts across language barriers and speaks to universal experience. These past few months in quarantine as I’ve been often overwhelmed with my own yearning and nostalgia for times past, Fado has become my isolation soundtrack.

So for your lockdown blues, I’ve put together a playlist with some of my favourites from Fado, some Fado-influenced pieces and some inspired collabs highlighting African influences for a healthy cure of saudade. I hope you enjoy it.

When Sebastian is not bathing in Fado minor chord progressions, he’s plotting new ways to compose Portugal trips. He’s waiting for the day he can head back to the Fado taverns, but in the meantime would love to talk to you about the story behind each selection on his playlist.