the moxie and pluck of Burt Kerr Todd

the post office essays

There is a particular magic we humans get to do. We can have an idea then translate it into a series of symbols which others, years later, can read, so that the idea enters into their mind. We can write and create books and essays and letters, and mark down our histories and stories and thoughts and dreams, and have others read them, understand them and carry them forward: a conversation over decades. Libraries and Post offices house this magic. This is the third in a series of three essays dancing on this theme.

I could feel the salt on my face so I knew that I had a brine to me. I woke up being licked by a firm tongued cow on the side of the road, “the Lateral Road” as it is called, the main road that leads through the mountain kingdom of Bhutan east to west. I had fallen asleep after biking for the past 16 hours over 3 Himalayan passes on a rental bike, in what can only be explained as a midlife crisis entry into the world’s toughest one day Mountain bike race, the Tour of the Dragon. I had “trained” but I really had no idea what I was doing. The best thing I had going for me was that I was just happy to be there and to be a part of the race – the competing and finishing wasn’t on the cards, so when I reached the bottom of the valley in Wangdi, one valley away from the finish line, I knew I was done and laid down on the side of the road to take a wee nap, for I am one for napping. Bhutan is a place where dream states like this happen, often, low oxygen and high altitude I suppose, so it was a fitting state to be in.

There is a scene in the second Indiana Jones movie, “The Temple of Doom”, where the three main characters jump out of a crashing plane to land on the side of the Himalayas. They then slide down the mountainside off of a cliff into a raging river, and within the span of a minute-and-a-half of Hollywood action, are in the plains and deltas of the Indian Subcontinent. Bhutan lives in this zone of dramatic transition; it is the south side of the mountains and the country, from North to South, is a slope filled with valleys.

Up until recently, to enter into this zone, this kingdom, one had to post up in India and walk, as there were no roads into the country, only trails. This was until the first road was built in Bhutan, in 1962, the same year astronaut John Glenn whirled around our planet in a pod of tin going 28,000 kilometers an hour. Sixty + years ago, less than a life span ago, a saeculum.

Before then, if you wanted to visit Bhutan, you would most likely start in India, in Kalimpong, a town 50 km east of Darjeeling, and ideally from the Bhutan House, a residence/administrative house that was a certain kind of government seat for Southern and Western Bhutan. If this is confusing, it is because it was, sort of. But not too dissimilar from Darjeeling being the administrative seat for exiled Tibet. The seats were run by Dzongs, or large fortresses (the regional capital fortresses, a distinctive type of fortified monastery found in Bhutan and Tibet), think castles and landholdings in western Europe. Again, it is a land of altitude transitions, the opposites of the American prairies. This was a place that was tucked away, past the foothills, and to enter in you would approach a certain way, a certain time, it was remote by nature as well as by design. In this part of the world there are magic landscapes called Beyuls where things thrived in the remote high altitude, and Bhutan contains a series of these sacred places. In modern travel parlance, the space between point A and B is a series of airline points and lounges, but here it was a glorious struggle, an eight day trek needed to reach a Kingdom.

India, specifically British India, had a particular relationship with the Kingdom of Bhutan. As a landlocked country, sandwiched between India, Tibet/China, and some serious landscape, Bhutan tied up with India on a handful of things, including administration of the post, the mail. Pre 1962, without roads or airports, all the mail was brought in through this trekking route from Kalimpong, and the Dzongs would have runners who would take the mail from Dzong to Dzong across Bhutan. These were literally people who ran with bags full of mail, from valley to valley, fortress to fortress, castle to castle. This is still done in one of the really far off corners of the country, Lingzhi, high up in the mountains.

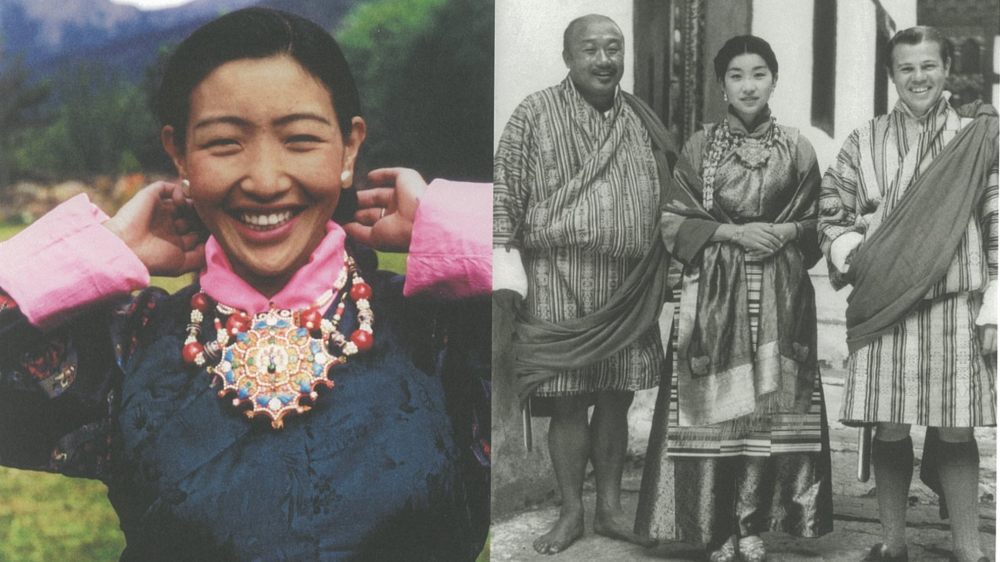

In 1951, this difficult approach into Bhutan was to be the case for Burt Kerr Todd, but it wasn’t his first time there. He had been on a round the world tour with friends in 1949 and had passed through then. In 1951, it was for a particular reason, a wedding, the wedding, the Royal wedding of the ruling family of this himalayan buddhist kingdom.

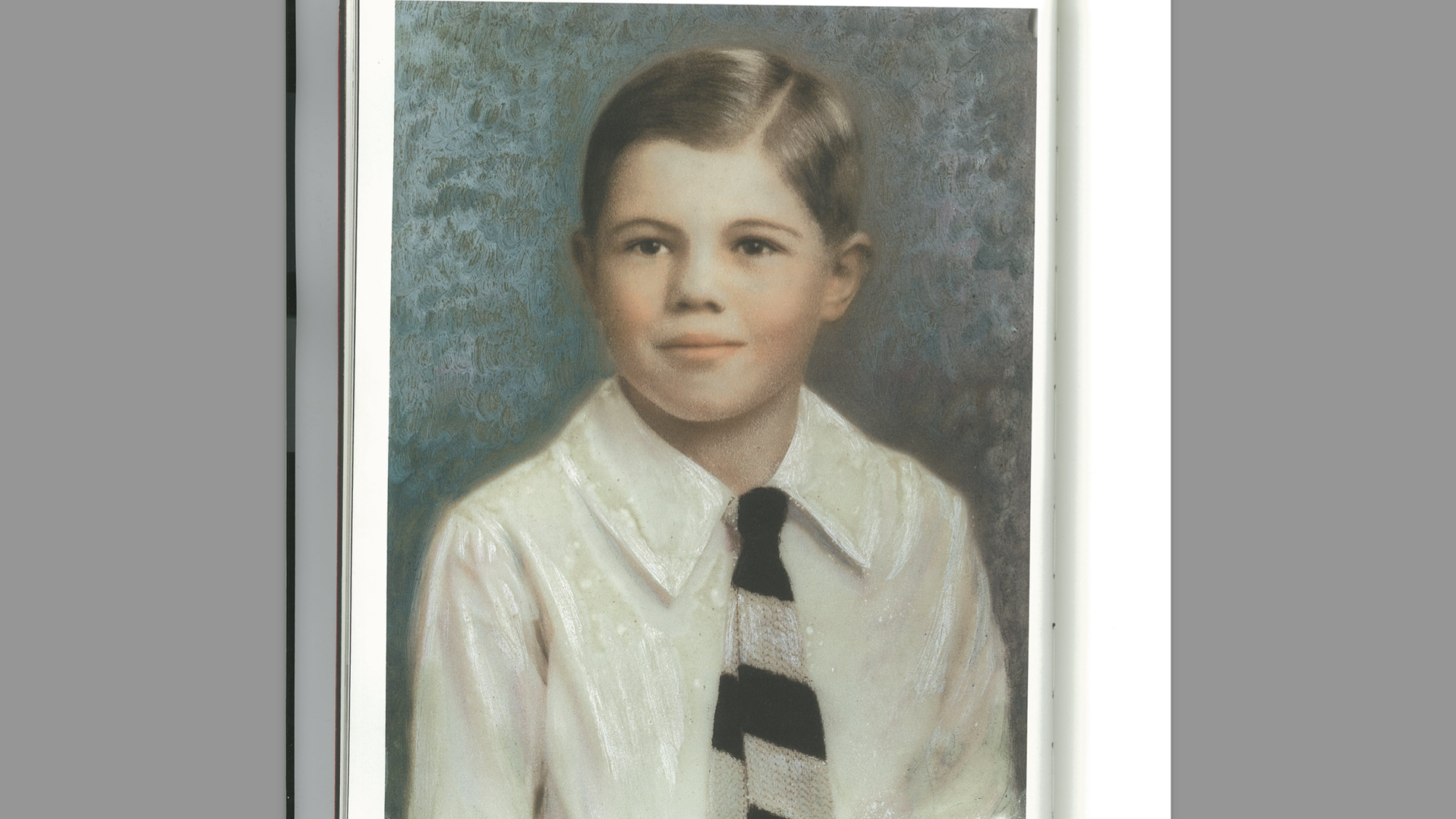

Burt Kerr Todd was born in Pittsburgh on May 15, 1924, the son of a wealthy Pittsburgh steel, glass and banking family. He had a reputation as the bane of the Pittsburgh long-distance operators, in a time when you would pick up the phone and the operator would ask where you want to reach, his list would have them patch him a call to Bhutan, Fiji, and God knows where else. He was telephonically ahead of the times. And imagine the time zones differences – he would be calling at 2 am, 4 am, the steel town midnight crew had to caffeinate and buck-up on geography to keep up.

Post World War II he wanted to go to Oxford for study and was told the admission staff head was on vacation in the far north of Norway and that he couldn’t be reached, so Burt jumped on a plane to find him and get himself into Oxford. He was a persona of immediacy and would seize a moment, wouldn’t let time pass by. He was that rare breed that had confidence in the fact that they were meant to be in the books. Oxford led him to meet an array of people from around the globe, one of which was Ashi Kesang-La Dorji, the soon to be queen of Bhutan.

The Wangchuck dynasty of rulers in Bhutan (which still rule the country today although now it is a Parliamentary democracy) were about to enter into their third King, King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck. Burt was invited to explore.

He met folks along the way, he had ideas. He and the Royal family, the leading politicians, the leading powers of the kingdom of Bhutan, would brainstorm, new thoughts on running a country. Bhutan was struggling to come out of an ancient world into a new world, it needed money and infrastructure, it wanted roads.

There is a story the Todd family tell about Burt and Prime Minister Jigme Palden Dorji being in New York City together. They came to meet with people at the United Nations and the World bank to talk about options for Bhutan to raise funds. It was on this trip that the Kingdom of Bhutan asked the World Bank for a $10 million loan, and were told to look elsewhere. The country was in need of infrastructure and schools, it was starting to form itself into the Bhutan we know today, a deliberate attempt at a certain way of organizing, at a certain way of life. The bankers they met with asked if there were mines, and they explained there was copper and coal but no roads to get there, there was hydro but no generators, there was an ideal for tourism but no airports or stations to bring people. Exhausted, they stepped into an elevator and Jigme said to Todd “what are we going to do Burt? Bhutan needs a way to make money.” And as the fates would have it, a man turned around and said as he stepped off the elevator, “Why not try postage stamps? You take a piece of paper and print whatever amount you want on it”, and then he disappeared into the crowded hallway.

Stamps it was, and Todd’s creative heart took charge. It wasn’t a far fetched attempt – the tiny city-state of Monaco had done the same thing several years earlier. Monaco’s Prince Rainier III called them “the best ambassador of a country.” So in 1962, Bhutan followed and set up the Bhutan Stamp Agency placing Burt Kerr Todd in charge.

Lines of communication become avenues of change, and we forget in the world of gigabytes and hard drives how the analog process of writing down a message on pulped wood, wrapping it up, and having someone walk it miles and miles away, was, and still is, a direct line of the motion of thoughts and ideas from one to another.

I read accounts of Mallory’s expedition to summit Everest (Chomolungma) and in the tellings of this story there are mail-runners bringing messages back and forth between basecamps and Capital cities thousands of miles away. Like the old saying about Fred Astair being great, but Ginger Rogers did everything he did, backwards and in high heels; the mail runners of the Himalayas were sprinting back and forth on the same trails and altitudes that the famed climbers were.

Todd wasn’t a man of philately, he didn’t know the world of stamps, and a particular world it was. What he did know was flamboyance, and marketing, and so he decided to create stamps that would stand out, outside of the box. It took a few years to get the groove going but they had their first big hit in 1967 when they produced the world’s first three-dimensional lenticular stamps. Then in the early 70’s the true creative masterpiece was the talking stamps, tiny records that were used as stamps, but could also be played on a record player, with the history of Bhutan, music, and folklore explored; and in 1973, Bhutan’s greatest source of revenue was its stamps.

It didn’t stay that way long but was an early step in a direction we would all come to know as modern day Bhutan, a country often used as an example of how a country can be intentional and deliberate in its motion of modernization, on its own terms. A country with both roots and with flexibility, that rare mix we are all looking for in a country, business, or individual. Size matters – it matters in business, it matters in groups of people, it matters in countries. Bhutan has just shy of 800,000 people in total, it is movable, and able. The ruling family, the Wangchuck dynasty knows this, and have been deliberate about how the country moves and shakes.

I had heard of Burt Todd through a friend who knew the family. She asked me one day if I knew about the talking stamps of Bhutan. I had not, and she clued me into the niche history. It stuck, and after guiding there for years as well as my mid-life mountain bike ordeal I remembered the story. Bhutan is a strange mix, a strange mix of striving for perfection while being faulted, much like the pillars of Buddhism, a self conscious understanding of limits and faults while continuing to strive towards a higher goal.

When I first started guiding there I had a tough time believing that all were happy, and indeed all were not, but that is part of the process of this country, understanding that no matter what, all will not be happy, but if you set up a few key things, more people can be. I sought out the punk rock scene in Thimpu, the capital city. I knew the prescribed dress of the Kira and Gho, a long plaid robe, would not play well with skateboarders and punk rockers, the early 20 year old set, who had lived or visited Bangkok, and who had seen and tagged and skated the urban. And I found them in Thimpu, in the early 2000’s, working on street art, and BMX biking, and wearing Nirvana t-shirts well into late morning when all were supposed to wear a Gho. But at the same time, it wasn’t a violent revolution, it was exprestion and eventually was embraced by the culture. This is what I mean about the dichotomy of being both rooted and flexible.

My friend who knew the Todd family put me in touch with Burt’s daughter, Frances, who not only had her father’s knack of running interesting businesses, but also kept the family stamp history alive by creating a series of CD-ROM stamps for Bhutan in the mid 2000’s. Businesses come and go but the family has kept its close relationship with the mountain kingdom. This is the effect this country has, it is like visiting someone’s home, once you go, there is a closeness. Bhutan has been trying to figure out a niche in the world, a way to survive, a way to participate, but also a way to adhere to a set of principles that didn’t go against a criteria for happiness which had to do with preservation and environment.

The stamps promoted an idea of place which educated, reached into your home and your ears, and allowed you, for a brief few minutes, to hear the sounds of a place without having to fly over a planet to see it, it allowed you to transcend.

Bhutan is now in another state of shift, as we all are now that covid changed things. Again, it is a small country, hidden and sandwiched, so it not only can deliberate about change, it can act it out fairly fast. There are new fees for anyone wanting to come to the country, a price to pay to visit, a deliberate financial fence put in place to make sure the country does not become Venice, Angkor Wat, Machu Picchu.

Dr. Tandi Dorji, Bhutan’s foreign minister and chairman of the Tourism Council of Bhutan explains “Covid-19 has allowed us to reset, to rethink how the sector can be best structured and operated, so that it not only benefits Bhutan economically, but socially as well, while keeping carbon footprints low, in the long run, our goal is to create high-value experiences for visitors, and well-paying and professional jobs for our citizens. ”

There is something essential in size and intention.

I find myself having the same conversation over and over, the same theme popping up in different places like the first growth in a garden. Historically when this happens to me, it is a sign of change, of things to come, future notes, spring. The conversation is on the subject of travel and tourism and it starts with questions asking what are some successful examples of businesses that serve communities, that aren’t consuming and extractive, that are built by a place for a place and a people. I keep having this conversation and the list is small and experimental. I talk about places like Shorefast and Fogo Island, conservation efforts for flora and fauna in African plains, certain cashmere manufacturers in Nepal and Mongolia, fringe small hotel groups, and I talk about Bhutan.

In each of these places there is humanness built into the business, an empathy, community. At a certain size this gets lost, but if you have the right size, the right intent, and priorities in a certain order, community and humanness can thrive. I like to think this is what Burt was thinking about when he made those stamps. To hear the voice and song of a place shoots right through to the heart of a person. It is why songs can expose a soul when sung well. I like to think this is what Burt had in mind, a platoon of little singing stamps being sent out into the world to help grow empathy, understanding, education, and love.