I, Claudio

Speaking as both an individual of Chilean descent and a lover of all things Morocco, it took surprisingly long for Claudio Bravo to come into my orbit. Surely due in part to the fact that in neither Morocco nor Chile was Claudio Bravo ever particularly well known. Even to this day, no museum or art gallery in Morocco holds one of Claudio Bravo’s works despite the fact that the last forty years of his life were spent in the Kingdom. As the saying goes, one is never a prophet in one’s own (adopted) land.

Bravo was a hyper-realist painter, taking subjects and recreating them to such painstaking detail that when viewed they looked like photographs. Hyper-realism goes beyond photorealism, painting exact features of a subject (working from photographs), raised to an almost maniacal attention to detail injected with a narrative and sense of a new, previously unseen reality. The philosopher Jean Beaudrillard coined the term “hyper-real” to describe when consciousness loses ability to distinguish reality from fantasy, “the simulation of something that never really existed”.

Bravo received very little formal training in art in Chile before moving to Europe to perfect his craft and spent years in Spain, painting portraits of high society. I can’t help but think that his exposure in Madrid to works by Velazquez and Caravaggio in the Prado planted their influence in his painting style. In the 70s he wound up in Tangier, counting such literary figures as Paul Bowles as friends. He also formed a long term friendship with the Shah of Iran’s widow, Farah Pahlavi, who would influence him to move to Marrakech and in the later part of his life to Taroudant, always in pursuit of ideal light conditions with which to paint.

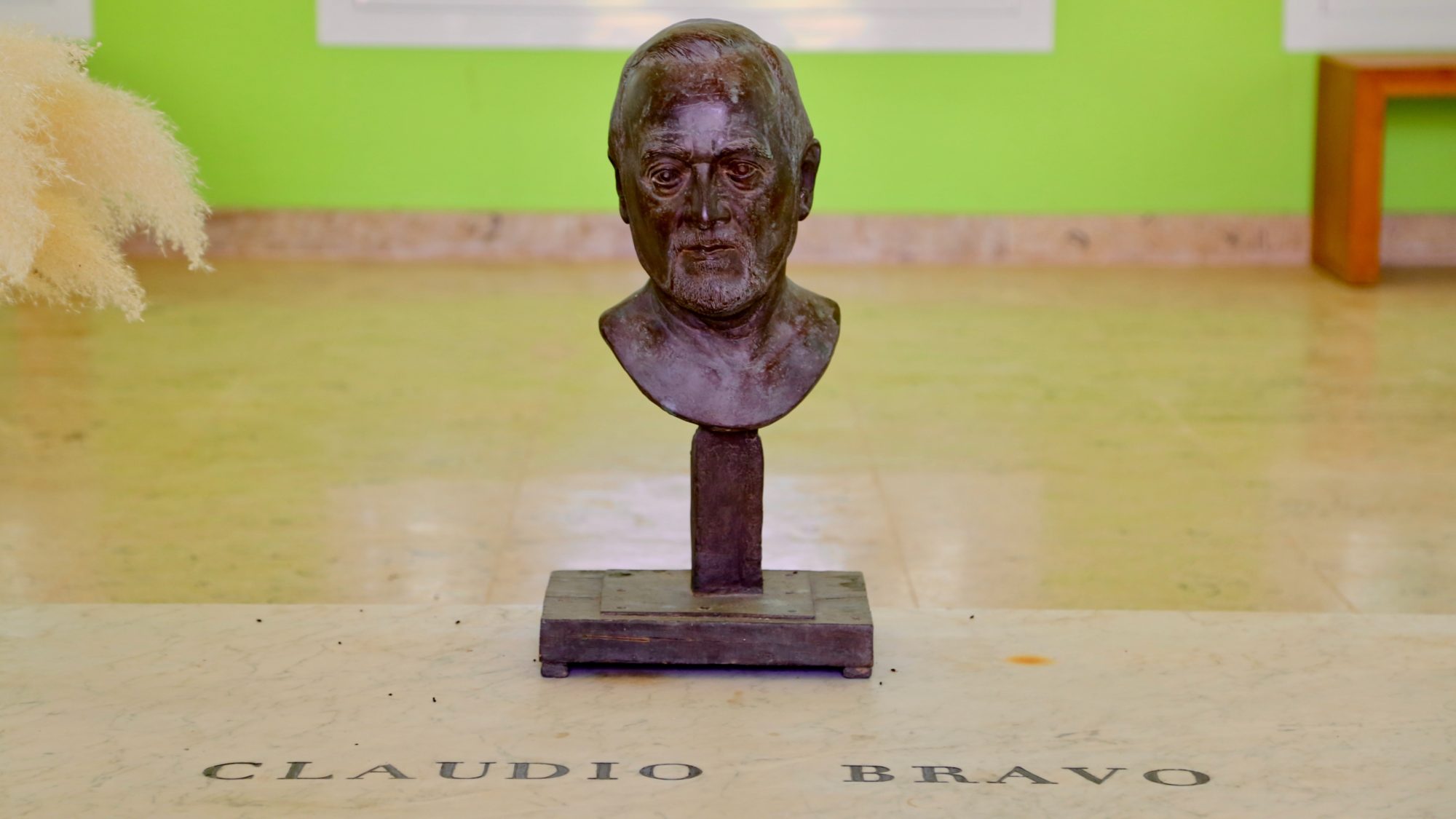

Here, he built a villa worthy of a retired Roman senator or a feudal Pasha, an enormous patrician country estate with large rooms, verdant courtyards, patios with Indian antique furniture and murmuring fountains, a sizeable replica of Marrakech’s Menara gardens, and most touchingly, a Moroccan marabout, or saint’s tomb, the kind found dotted all over the country. It is here where his Moroccan caretakers decided to create an homage to him and where his body is buried. Today, Claudio Bravo’s home and mausoleum make for one of Morocco’s most unique museums.

That Bravo’s paintings hanging on the wall are not originals but replicas (his sisters inherited the paintings and took them back to Chile), is almost irrelevant – the way the house was constructed to take maximum advantage of the sun throughout the day, the play of light and shadow against the walls, the furnishings, the columns and patios, the objets d’art strewn throughout the house (Bravo was a prolific collector) create the effect of blurring what is art and what is real. It recalled for me the vignette in Akira Kurosawa’s film Dreams, where a modern day admirer through magical circumstance walks through Van Gogh’s actual paintings. Sauntering around his property one almost felt like an intruder, that at any moment Claudio Bravo could walk in. Personal effects, furniture, his stylish De Velasco capes, all have been left in their place, even Bravo’s toothbrush and preferred shaving cream still stand on the bathroom sink.

While he was still alive, Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa wrote in a foreword to a photo-book collection of Bravo’s work: “It is not in the least surprising to come across the faces who posed for his Christs, martyrs and anchorites, his Madonnas and diviners, his bird charmers, dancers and musicians, his characters from mythology…They are in the kitchens, they are the family of the caretaker, the gardeners, the cleaning ladies, the man who looks after the pigeons.”

Bravo lived his life with his personal secretary Bachir Tabchich and Bachir’s family, who along with members of his old staff still live on site, maintaining the property, and offering visits of the home by appointment. When I met Bachir he was delighted to learn I was of Chilean origin and proudly walked me through the home, pointing out reproductions, pieces of Bravo’s collection that made for subjects of his paintings, the dining room where Bravo’s glitzy expat friends would wine and dine the evenings away (“This was Jacques Chirac’s seat, and this place was always reserved for Farah Diba”). In the delightful and cluttered studio the chair and easel at which he was working was still set and the last subject he was painting, a red cape, still hanging on the wall. It was here that Bravo suffered two heart attacks before passing away in 2011.

The museum and Taroudant take some effort to visit, and the destination is not one of the more obvious highlights of a trip to Morocco – all the better for Taroudant and those looking to go beyond the obvious and get away from the usual tourist masses. It can make a great couple night’s stop on a longer Morocco trip between Essaouria, the High Atlas, and the desert. With the once legendary Gazelle d’Or closed now for years, it’s out in the dusty Palmeraie quarter where you’ll find the best place to stay. Most residents still live intramuros, as Taroudant never had the French ville nouvelle associated with cities such as Fes or Marrakech. Incidentally in the Palmeraie is the residence of Pahlavi herself, who still spends part of the year in Taroudant. Aside from an extensive and well preserved medieval pisé wall and a fully functioning local Medina, Taroudant lacks the obvious tourist attractions but exudes a faded nostalgic calm and sense of discovery.

Before bidding Bachir and the Claudio Bravo museum farewell, I peeked into Bravo’s bedroom, and spotted on his bedside table a well worn copy of Don Quijote. I can imagine him at night before bedtime poring over Cervantes’ words and pondering the story of the crazed knight tilting at his windmills. It seems a most fitting eulogy for the life of an artist: “When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams — this may be madness. Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!”

When Sebastian’s not tilting towards his own windmills, he spends a lot of time creating Morocco trips so good they’re surreal. Get in touch to get planning.