The Good Abbot Wang

The Post Office Essays

There is a particular magic we humans get to do. We can have an idea then translate it into a series of symbols which others, years later, can read, so that the idea enters into their mind. We can write and create books and essays and letters, and mark down our histories and stories and thoughts and dreams, and have others read them, understand them and carry them forward: a conversation over decades. Libraries and Post offices house this magic. This is the first in a series of three essays dancing on this theme.

I find myself trying to teach my children how to live like Victorian scientists: how to be curious and to explore, to pick up the old maggoty bone off the forest floor, not to fear it or think it gross, but to be curious about it and look at it to learn. I didn’t expect this as a parent. I knew I would preach but I didn’t realize how much of this particular gospel I would cast. In my own youth I was curious enough to pick things up off the floor, but sometimes it was other people’s property that fascinated me, sticky fingers. Once I had a Piano teacher, and sitting in her house one day waiting for my lesson, I saw in a stack next to her fireplace: sepia-tinted rolls covered in Chinese script that I am sure must have been purchased in a market in Beijing on a recent trip. Every week for a month I would sit and stare at these scrolls prior to my lesson, lusting after them for no other reason than their strangeness… until one day I succumbed and took a scroll, quickly shoving it into my backpack.

To be a scientist is a fairly new concept, the word first occurring in the lexicon in 1834, coined by Cambridge professor William Whewell. A couple of hundred years earlier, Francis Bacon changed how we think by conceiving of what was to become modern day science. Bacon shifted the accepted idea from the Aristotelian model of thought experiments, to actually going and seeking out empirical evidence, leaving our dialectic comfort and going out into the world to collect things so we can look at them and learn about them. A philosopher’s want for a library of things. Travel was central in this idea, you had to leave and come back with collected things and contemplate them, write about them; “Many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall increase”. A long driveway that would set off the Enlightenment and end at grand Museums and the plundering of antiquities. The want and need to go out and collect things became a great game for the new world order of the 1800’s. It resulted in such anomalies as the Venus de Milo in the Louvre, and the head of King Ramses II in the front foyer of the British Museum.

In a simplification of world history, one can imagine a time when the isolated corners of the world first crossed paths. Thousands of years ago, as road systems and transportation technologies opened up and the distance between oceans and deserts became smaller, as clustered groups of humans started to venture out past the corners of their maps. The Himalayas separate a large swathe of the world, one side distinctly different from the other. When a road was built through the passes, it was the beginning of a great change for both sides of the vast mountains and was the first time these cultures would clash and meld. The marks are left from this moment, and you can put your finger on the exact spot on the map where it happened, and see the writings on the wall.

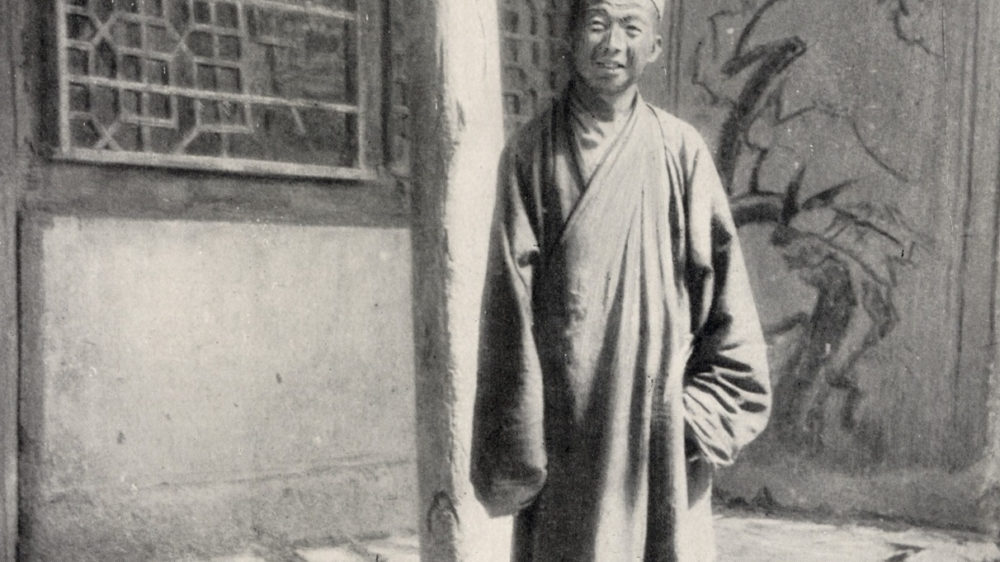

In between the Gobi and the Taklamakan deserts in western China, down hill from Tibet, there is an oasis 10 km from the village of Dunhuang where all the roads converge. There is a large cliff of sand, and a small river coming out of the desert dunes, and a series of caves filled with iconography, from Greek gods to Hindu images and Buddhist Prayers. Here is the place where things changed, where one was either leaving China, or entering, where roads from India came north through the mountains, where trade routes from Europe converged into Asia, and Gods met for the first time: Buddhist, Christian, Hindi, Muslim, Jewish, Zen. Because it was the end and start of the road, it was a place of prayer. A place where thanks was given to Gods for having survived through the long haul, or hopes for being able to make it. A true frontier town. In the caves one would paint whomever one worshipped, letters would be left for lovers, friends or foes; books would be left, the oldest of books – it is where the Diamond Sutra was stolen, the oldest printed book we have presently in the world. A way station, a last will and testament, a post office, a library. The rooms in the sandstone wall were called the Mogao Caves, or the caves of 1,000 Buddhas, and for hundreds of years it was forgotten in the desert, like a dream, covered with sandstorms, encapsulated. In the late 1800’s a young Abbot from a sorted past, illiterate, and finishing his military work, decided to take on the caves as a moral obligation to watch, protect, and care for, a librarian who couldn’t read for the world’s oldest library; The Good Abbot Wang Yuanlu.

Wang Yuanlu shows up in the history books later in life. His early history is foggy, military at some point, then a travelling Taoist monk with few physical attachments. He shows up in the Mogao Caves when the European adventurers and treasure seekers first started looking for ancient books (in the mid to late 1800’s) – books that were slowly finding their way into the underground markets along the long dead Silk Road. Sometimes the books in question were fakes – good fakes, but conjured up. Then sometimes they were real, and they were magnificent. They were far older than many of the books held in the great museums of Europe, and they were printed with advanced technology, way ahead of their times, in amazing condition. For those in the business it was a gold rush which sent a handful of explorers out on the road in search of the lost library.

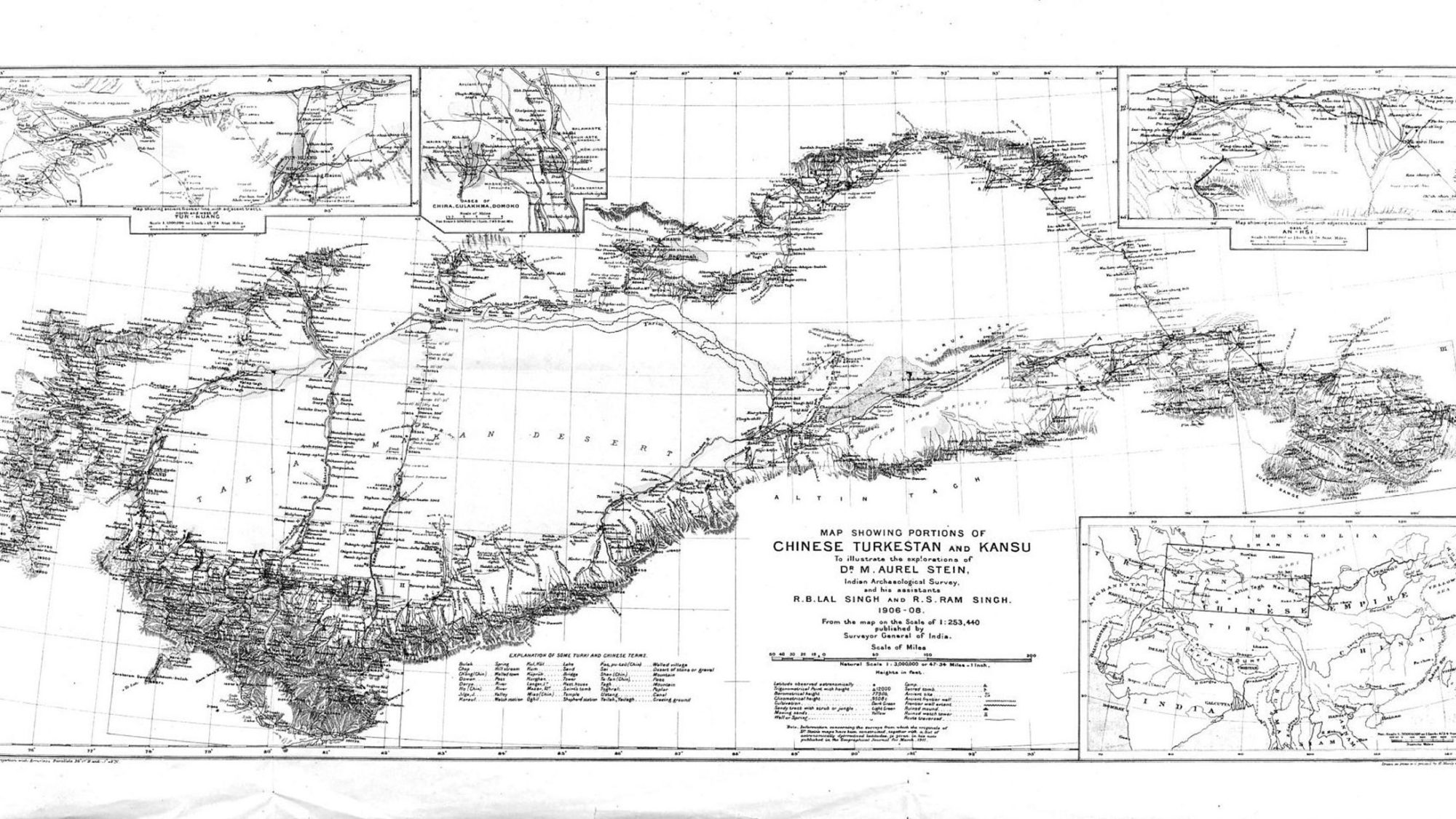

These treasure hunters were Indiana Jones types, and indeed many were used as frameworks for the Indian Jones stories. Many lost their lives in search. There is a vast desert in the middle of the Tarim Basin in western China, the Taklamakan, past the old Jade gate where the Great Wall of China reaches its terminus and the maps were unfinished. This desert consumed many caravans and explorers trying to cross it in search for lost cities. But a few would survive. Sir Marc Aurel Stein was one of the handful who would make a number of attempts into the desert in search of lost books and live to tell the tale. Hungarian born and of British citizenship, he was a player in the Great Game, a pre-Cold War intelligence skirmish played out in Central Asia between the expanding British and Russian empires. Sandwiched between these two masses was central Asia, the great chess board on which the game was played out.

Stein knew the forgeries, having found one of the main artisans creating fake books, Islam Akhun, in 1901 near Khotan on the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert. But there were real books out there as well, and he had seen them along the way. So he hunted the landscape in search.

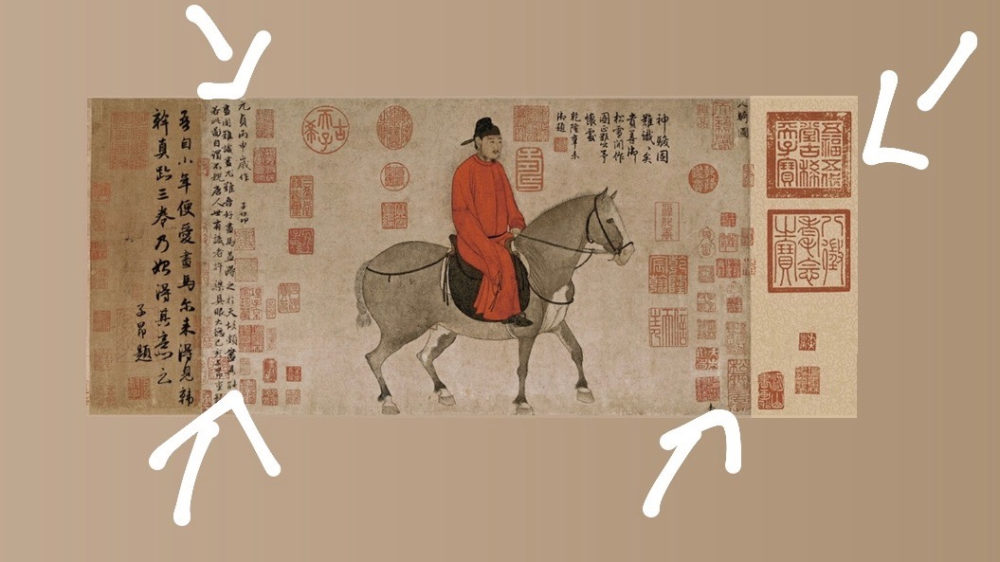

In Chinese art and literature (which are often one in the same as the language is traditionally written in pictograms), there is a relationship between the ownership of a piece and the object itself which is much more akin to the relationship in Western art between the artist and the object. If you own something, you are forever a part of that thing’s history.

This you can see in the artworks themselves, written on the fringes of the canvas, in what is called a colophon. A painting, rather than becoming something that is coveted and held, is something that is imprinted on by the owner, and then passed on for gain, political or personal. It is in many ways similar with modern blockchains and non-fungible tokens (NFT’s). When you acquired a painting you would mark it on the fringe with a message showing tribute to whomsoever gave it to you, as well as aspirations on what you intend to gain by having it. Then, you would pass it on. This is opposed to the European tradition of collecting and housing in museums, and keeping unchanged and protected. There seems to be a difference in function. Art in China was traded for political and personal capital, and while Western art is traded for money, and is a sign of status, it wouldn’t be marked with the names of the owners on the side of the canvas. Only the artists name is allowed in such sacred space; and that is part of the difference between the European and Asian concept of antiquity, the sanctity.

It wasn’t just names written on the fringes, it was tribute, poetry, storytelling, short histories of the transfers of ownership. This is the similarity with Blockchains: it would have the ownership history attached to it, and that history was part of the value of the piece, and it would grow as it was passed on.

The story goes that Wang one day, sitting close to a wall in one of the larger chambers of the caves enjoying a cigarette, noticed the smoke moving into cracks in the wall. He chipped away at the wall and slowly a door became apparent, a small opening leading into a library of scrolls, sepia in tone, with the world’s languages written across many of the pages. Religious books, personal diaries, news catalogues, love notes, packages left for others to pick up, thousands upon thousands piled as high as the ceiling. A post office of sorts, a way station. Wang knew the political and social value of the books, and hoarded them. He sold some to help fund the upkeep of the religious sites of the caves, and he gave some to local political figures, not in what we would today call a bribe, but in keeping with the way such objects had always been exchanged: as social currency. The local politicians traded them like Pokemon cards and some would surface onto the international market in places like Beijing or the British Consulate in Kashgar.

In the spring of 1907, Wang returned from a pilgrimage to find a man, a Hungarian born British citizen, looking for artifacts to bring home to the British museum. Snooping. The treasure hunter Stein.

Wang must have been sceptic, at least at first. Word had gotten around that there was a hidden library. Wang had even bricked up the opening to keep out wandering eyes and grasping hands. He had already used many of the books as currency with local politicians and leaders, to help fund the restorations of the religious sites of the caves. Again, the idea of history and heritage is not one of perfect, static preservation in amber, but of preservation of a way of doing things, of a culture. Religious spaces must be used, and must be maintained and updated, rather than walled off and looked at from afar. So when Stein offered to buy the books, in order to restore and save them, as well as to spread the gospel of their teachings, the abbot Wang agreed.

It was a deception, however. The intent was to collect and hoard rather than spread the word, and it was a finders-keepers treasure hunt for objects, intermixed with intelligence gathering in the name of the Crown, since Stein was not just an archaeologist, he was a spy.

Truck loads were taken out, including the Diamond Sutra, the world’s oldest printed book. When Stein was finished, others followed from other countries and organizations to clear out what remained. Texts and books were spread all over Europe in museums and collections, to Berlin, London, Paris and New York. The Diamond Sutra still sits in the British museum as do many other texts in the Met in New York, and the Louvre in Paris. Sadly, many of the texts were bombed out in World War II when the museums of Berlin were destroyed.

By the time I first went to Dunhuang, it was long after the pillage. It was a place on the tourist maps for academics, and for Chinese domestic tourism, but not for mass tourism. The caves were known and protected in a loose sort of way, with no fence around the place and with high school kids going there at night to drink and light fires in the caves. The local museum was selling evenings in the caves for private dining experiences, and you could still take flash photography of the frescos if you so wished.

I landed in Dunhuang and it was one of those far away airports where the plane lands on a strip with no other planes are around, and a stair case is rolled over for you to walk off the plane onto a field and shuffle off to wait for the luggage to be tossed out the back. It was exciting, and it was far, far up the Gansu corridor, a long valley that led out of China into the unknown.

I wanted to find a living connection with the past, with Abbot Wang. I wasn’t interested in looking for hints of Stein’s presence in Dunhuang, or any of the other explorers. I was interested in Wang, how he lived out his days, where and with whom. I wanted to connect my life with his by sharing the same space or story, even though it was 100 years apart. There is a word, saeculum, that describes this, the measure of a lifetime linked to an event in the lived history of a place. It means the time from the moment that something happened until the point in time that all people who had lived at the first moment had died. A measurement of a collective lifetime and memory. I knew signs of the good Abbot Wang were still somewhere in the oasis, and I searched for them. I also had the dream of walking to the caves through the desert, rather than going by car across the highway, freshly paved from the town to the new train station and then onwards to the caves. On the maps it looked easy to me, like a big horseshoe bay, walking from Dunhuang on one end of the bay, through the desert 10km to the caves.

The line where the oasis of Dunhuang ends and the desert begins is stark and straight. The trees and growth stop abruptly and then it is empty and dead. There are graveyards on the outskirts, in the first few hundred yards after the end of the green, then empty rolling sand for miles. On the maps the closest point from the green growth to the caves out in the desert was at a bend in the road. It was there that I went, and there that I found a small functioning Taoist monastery staffed by three young Abbots. I knocked on the large red aluminium door and, along with my interpreter, was invited in for tea, so we entered the walled building on the edge of the desert. The front gate opened out to the dunes rather than towards the growth, the oasis. The three young Abbots and I had tea and talked. I asked about the caves and about the monastery and its location. They knew of Wang’s story and said it was possible he had come here but they weren’t sure. I asked if they ever walk to the caves, and they had a few times but most of the time they take their four-wheelers. They asked if I wanted to hire theirs rather than walk since it was long and hot. So I took them up on the offer, asked my interpreter and friends to drive around the long way on the new road and meet me at the caves, and off I went into the desert in the 4×4, headed due south-east.

I was terrified and thrilled, and the whole journey must have only lasted 30 minutes but I knew it was special and that I wouldn’t be able to do it again. The next time I would have some knowledge of place, and it wouldn’t be new. I rode up over sand dunes 50 feet high, and came to a peak to see the green small valley below of the Mogao Caves. I found a small ravine to drive down and came down on the North side of the valley, where the caves start, and found my friends waiting for me.

Some geography is sacred – in Ireland they are called thin places, where the veil of mystical and physical is stretched – and this valley you could tell was special. I explored the caves with a guide, met with some of the Museum curators, and although found no confirmed sign of Wang and his life other than what was presented in the museum, I felt saeculum, I felt the connection of 100 years and time in a lifespan, that it wasn’t so far removed from the present to no longer have the pulse left in the atmosphere.

You hear about the last surviving soldier from some long ago war passing away, and you can feel the collective memory start to fade even then. I was excited to still be in a place where someone was alive who knew of the Abbot in his lifetime, of the explorers who came to plunder, of the caves being forgotten in the saeculum of space and then born again through lust of archaeology and science.

I like to think that I regret stealing that scroll from my piano teacher, but I don’t – I have tried to feel bad about it but it just isn’t there. I took it and for a curious mind it fed a hunger that was overwhelming in my young self, a wanderlust in an artefact. It was like hen’s teeth, if you came across something like that, in my small town, someone like myself, the impulse to reach out was irresistible. It felt like it was my duty to steal that scroll, to spark in me what eventually sent me out into the world.

I think, and here is my internal contradiction as both a thief of scrolls and a globalist, I think the artefacts that were taken by Stein and so many others should be returned, that they do not belong in England, or Berlin, or Paris. I understand that at the time, to those who went out to find those books and paintings, it was looked at as saving those artefacts from ruin, even if that wasn’t the case. It was a definition of science, a Baconian mentality of collecting and coveting. I think about the colophons on the fringes of Chinese paintings, and I wonder about the way we define things, how we think about collections and museums and zoos, at one point in time as virtuous, and at a later time as shameful. It is a curious action that precludes the ownership. How in Asia to own something old is to change it forever, and to join with it in its journey through space and time, to connect with it, imprint upon it your own mark.

I went back many times to Dunhuang and watched it change and grow. Now there is a fence around the caves and it isn’t as free-flow as it once was. For a time, things were moving in one direction in China, and it was exciting. It has now been almost two years since anyone was allowed a tourist visa into the country, a new locking-up has started, a retreat into itself, a new insular saeculum. I watch the Winter Olympics this year and am reminded of 2008, a summer that perhaps was the high water mark for an epoch of China, and how much of a contrast those games were to these, the summer to the winter, one full of life and hope, and another closed off and cold. I have hope that there are still places out there, where travellers hide letters to home, secret caves and post offices, trusting that they will be kept and delivered to those they love by others passing through.