On The Chasing Of Whales

The Post Office Essays

There is a particular magic we humans get to do. We can have an idea then translate it into a series of symbols which others, years later, can read, so that the idea enters into their mind. We can write and create books and essays and letters, and mark down our histories and stories and thoughts and dreams, and have others read them, understand them and carry them forward: a conversation over decades. Libraries and Post offices house this magic. This is the second in a series of three essays dancing on this theme.

I grew up in the southern US, in a Norman Rockwell town called Madison Georgia. Scientifically the books say Georgia has a humid subtropical climate, which I agree with. Mild winters, thick hot summers, and very short springs and autumns. It is surrounded by other states to the South and West, by the Appalachian Mountains to the North, and to the south-east, by the Atlantic ocean. It felt snug, and in terms of cognitive-geography it was contained.

Madison was not a large town and we were set in the middle of 300 acres of property that I enjoyed exploring. It wasn’t the way-out-wilds, but it was space, open. A solid mix of being in a community, but the opportunity for knowing solitude. The 300 acres I came to know well. I knew where certain fish lived, the rhythms of the insects, the sound of trees in motion at night, how to manoeuver around a briar patch when at a full sprint. It was the first time I had a deep relationship with a section of land. It changed me, it changed the way I relate to landscape.

My first international trip was to Mexico, the Yucatan. We landed in Cancun but only to rent a car and drive across the landmass to get to Merida, through the jungle and limestone flats. It was the first time I felt that level of vastness, wilderness, but it was familiar in the experiences of nature I had in my boyhood. Part of it was the landscape, but a large part was me being in a place I did not know – open and empty in my experience of it rather than in actuality. It represented the unknown.

For a long time I would seek this feeling out; at that point in time it was subconscious. I spent time in deserts, on oceans, in places where the maps were old and out of date. I sought and still seek the empty sublime.

Now I am settled in a new place, a new geography, and I have come to know parts of it, and I have noticed a difference from the land I knew as a child.

I live in Ontario, in the lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples. My family and I spend part of our time in Toronto and part of our time on the shores of Lake Simcoe, an hour North of the city. The first winter I spent in Ontario, the lake, as it does every year, froze over. I decided to walk across it. It was there that I first felt part of the difference.

In the winds and the snow there was a false sense of endlessness on frozen liquid. It is quiet, or filled with white noise with the wind and in its own way a sense of solitary noise makes it quiet. This is where the idea of the North began to start presenting itself.

There is a vastness that is omnipresent in the landscape of Canada. The North, a seemingly endless expanse of wilderness, always present, always pushing down on the bottom line of the border with the US. In Toronto, people talk about going ‘up north’ for the weekend as both a geographic and psychological state. The playful weekend up at the cottage to the north. But there is another North that looms and is mostly unknown, past the cottages, past the roads and railways, a North that is far, wide, and large, like a sea, the tundra and taiga. Even the terrain merges with the sea at a point, in sheets of ice, where it becomes a mesh of land and frozen water, seasonal, tidal, and moving.

Glen Gould, the famous pianist and composer, spent the later part of his career away from the piano, instead focusing on the North as an idea. He grew up on Lake Simcoe. He was obsessed with the vastness, and with the way in which landscapes like that evoke the sublime, and end up focusing one’s attention on the self rather than the land. He was interested with the way in which the North shapes part of the Canadian psyche, the culture. When you go North, you go into yourself. (If you have a spare 3 hours it is worth a deep dive into the counterpoint mind of Gould and his creations dedicated to the North: a radio program and a documentary series for CBC). I wonder if the frozen Lake Simcoe gave him the same slice it gave me of the sublime.

The North attracts those lost souls trying to define themselves. It is a place to go and hide, and to seek. There is a dichotomy in this intention, this want to explore into the self. In opposition to focusing on oneself, there is also a reaching out, a searching. In this state of seeking and wandering, even the pirates get homesick. When you strip everything away, we all want friends, food, shelter, a hug now and then perhaps (maybe not for all), and word from home; no matter how swashbuckling we pretend to be in daylight hours; deep down, in places we don’t talk about at parties. The North, the desert, the mountains, and the sea, the sublime regions of the great green earth. To me, going North and going to sea are the same motion, the same journey into the self. It magnifies things, and focuses, it reduces. Bush pilots with beaver pelts and whale hunting pirates.

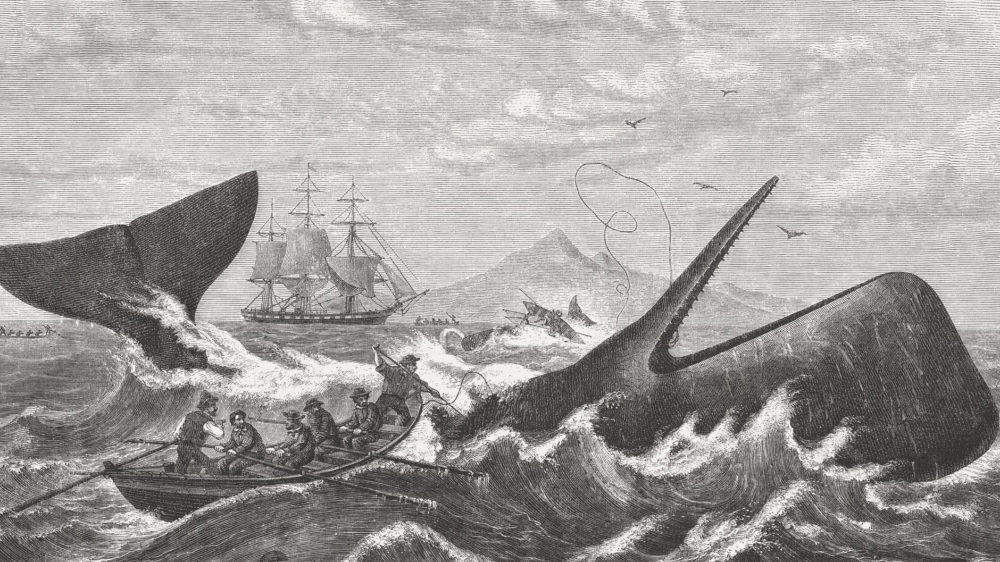

At first, the distinction between pirates, buccaneers, privateers, whalers, sailors, company men, and the military was not very clear. Pirates initially were just sailors for hire. It was in retrospect where they became Johnny Depp. Mostly though they were sailors, and often they were on the hunt for whales. There was a time period when sperm whale oil was the prime natural resource for the industrializing world, when it lit the streets of the cities we were building. The search for this resource sent us far out onto the oceans; this was before the first Petroleum well was tapped in Pennsylvania. It created a well-paid harsh job for those who willing to go to sea, to seek themselves, find themselves, have adventures, and feel the vastness, as well as make a small fortune if one could survive.

Crude oil and coal mines are the newer version of that corruption of the globe, the natural resources often are found in those far off sublime quarters, the deserts, the North, the sea, or even unobligingly trapped within beautiful living creatures.

My partner is convinced that when she sees me reading Moby Dick that I am depressed. A bellweather for my mental health. It is a good instinct since it is a book about a depressed man going to sea in order to refresh his life through the chasing of whales. Melville writes:

“Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship.”

Melville had a habit of burning all his letters and notes. He burned the bridges behind him forcing motion forward, like Cortes and his boats. He had spent time hunting whales in his youth and was inspired to write Moby Dick after meeting the former captain of the Essex, a real ship that famously was attacked and stove by a sperm whale in 1820, the accounts of which were recorded by the 8 survivors of the ordeal, a long struggling rescue that resorted to cannibalism at times.

Prior to its sinking, the Essex sought refuge in Floreana Island, Galapagos. The crew took over 300 tortoises for food. This was a common practise and provision for whaling vessels in the Pacific in this time period, which resulted in the species’ risk of extinction. Melville came here as well, in 1841 aboard the Acushnet, a whaling ship he was working in during his early 20’s, learning the sublime and the sea. Because of its location out in the doldrums of the Pacific, the Galapagos were not just refuge for species, but for those seekers of the North, seekers of the sea. It was a place to stop and hide things like stolen treasures, it was a place to gather food and water, and miraculously, it was a place to touch home through letter writing; to reach out of the depths of the sublime and think to the warm hearths of Nantuket and Hull.

A tradition began, sometime in the 17th century, of leaving letters in a wooden barrel tucked off a beach on Floreana Island. It was first called Hathaway’s Post Office but eventually became Post Office Bay. You would leave a letter to home on your way out into the open sea, and if on your way back, you would look through the letters and take with you any that were close to your destination port, thus creating a post office of sorts for the seas. There was no bureaucracy attached to this process, it was just known, and done, and respected; a tender human capacity. Whalers, pirates, company men and women, military, explorers all alike would respect this tradition of the sea, and still do.

Floreana is not populated with cities, towns, or villages, but is small, naturally protected, had a source of water and food, and was a refuge miles away from mainland, in the middle.

History books often skim over the peopled history of the Galapagos, instead focusing on the inspiration for Darwin, the variety of fauna, the variety of the finch. But there has been a strange and fascinating human history to the islands, the current population being 25,000 people. The cities are limited to a few islands (Floreana not being one, although it was lived in by a few families).

I first landed on the shores of the island in 2007 guiding groups off of one of the large ships that sail these waters, bringing people to the national park to see the variety in flora and fauna. Guide is a strong word: I managed morale and I entertained, so I knew nothing of the geology, zoology, nor ichthyology. My first tour in the Galapagos, I didn’t know what Post Office Bay was until I was standing in it and looking at the barrel letters still making their way around the globe. I was skeptical and young and thought it was a gimmick put in place for a lack of anything else to do on Floreana. I wrote a letter to myself noting that if this letter was ever delivered, to check my jaded self at the door and be more open in the future. Then I went on my way guiding the rest of the trip.

At that time in my life I was guiding 11 months of the year, on a circuit that was winters in South America, Spring and Fall in Asia, and summers in Europe. At the end of that first trip in the Galapagos, I was asked to guide in Myanmar immediately after so flew from Quito to Yangon, a long 3 days of transit. It was a month before I actually went back home to Georgia. When I arrived, I was told of a stranger driving up to the house with a letter in hand to be delivered to me, like in times of old. It was my card from Post Office Bay, picked up by someone in the Galapagos who knew they would be passing through Madison Georgia. I was gobsmacked.

The next winter I returned to Ecuador and the Galapagos and when I landed barefoot on the beach at Post Office bay, I was ready to take some letters with me to Asia, Europe, and South America.

Over the next 6 months I hand delivered over 20 letters to people in various countries and cities around the world. I would be invited in for tea, dinner, weddings, bar mitzvah’s. Sometimes I made life long friends, and sometimes I just delivered the mail.

There was a magic in that human enterprise, which had no aims of financial gain – no one was selling or buying anything. It was set up by homesick sailors and pirates wanting to reach out into time and space and touch home and connect. It was and is beautiful.

I imagine Melville wrote home on his journey, a man of letters and the written word. How could he not, he must have, and somewhere out there are the lost Galapagos letters of Melville, sitting in a cupboard of some long line ancestor. Or perhaps he burned them all as he did with many other letters, a sailor’s philosophy of never looking backward. And then I think of all the letters that have been hand delivered through Post office bay, seasick sailors words to home, hand delivered by other travelers passing through. How one can write out their heart on a page, and have it travel through space and time to land in the hands of a loved one, who can then read the words and thus feel the love.

I traveled through the Galapagos over 20 times, and I will remember the birds, the penguins (there is a small bread that lives there), the tourists, the people; but the thing that rises to the top isn’t what Darwin saw, it was this beautiful Human need being expressed in the doldrums of the sublime. Darwin must have used Post Office Bay as well, and I am sure he and many others felt the wonder in that, or maybe not, maybe it has taken the digitization of interactions to show the magic in slow motion of hand delivered mail through chance and serendipity.

Something happens to you when chasing whales, when going North, you have space and time with yourself. It takes an ocean not to break. Some come out knowing themselves a bit more, some come out not liking what they find. It is a strange transition, but even out there in the empty spaces, there are beacons, touchpoints with a sense of home.