Peach Blossom Spring

I like to dig, search, and poke around, and to stir up different ways to connect with a place. How to look at a city or a region with a different set of eyes, or better yet, with a different approach, like the way a pilot gauges the wind direction to land correctly on some small airstrip. It depends on the time and weather of the day. I feel the same with research for travel, and I spend most of my time daydreaming, reading, and pushing myself to talk with people in all sorts of different light.

There are different ways to enter that temple: read articles, read fiction and non-fiction, look at hotels, or focus on a sport or an activity that can be done in that place. I seek out people, finding them through social media or printed text. I will pick up the phone and call them, have meals and coffee and meet-ups with them just to talk about the place so I can wrap my head around what makes a place move, jump, and shout. To do this you must understand the stereotypes and archetypes.

I came from the culinary world, in a way, in an indirect way. I had to pay my way through university and decided that if I was going to work a part time job, it might as well be something I can learn from. So I applied to be a car mechanic at a few spots, as well as a chef. I didn’t know how to work on an engine or how to cook. I ended up in the kitchen and it taught me an ethos, a certain style of work ethic that only chefs know, a bleed-it-out loyalty. Although I wasn’t keen on a life in the kitchen, the late nights and hard living hustle, the work ethic stuck with me. After finishing my studies, I ran to as many places as I could and began a life on the road. A life in travel.

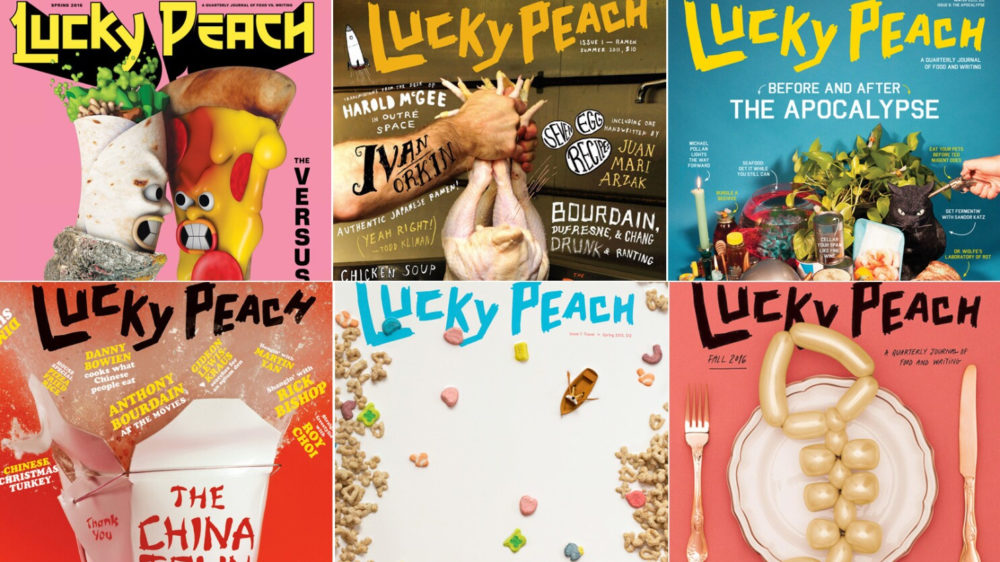

Oftentimes, because of my time in the kitchen, I start with food. I lived in Brooklyn in the early 2010’s (it was wonderfully/painfully hipster) and on a particular long weekend in Montauk one spring, a pop-up store was selling copies of a new culinary magazine called Lucky Peach. This magazine was something different, and even if you don’t know it, you know the effects it had on looking at food-writing and publishing. It is no longer in print, but for a few years it was a creative place for those interested in the pendulum swing happening in trends from tradition to street. It was vulgar, experimental, scientific and slapstick. It often focused on Asian culinary stereotypes as well, and after living in Asia for almost a decade, I was interested in what Lucky Peach was preaching, I was picking up what it was putting down.

David Chang, Peter Meehan, and Chris Ying began the magazine (Peter worked for the NYTimes as a food critic, Chris worked at Mcsweeney’s publishing, and David founded and ran Momofuku, which translates to Lucky Peach).

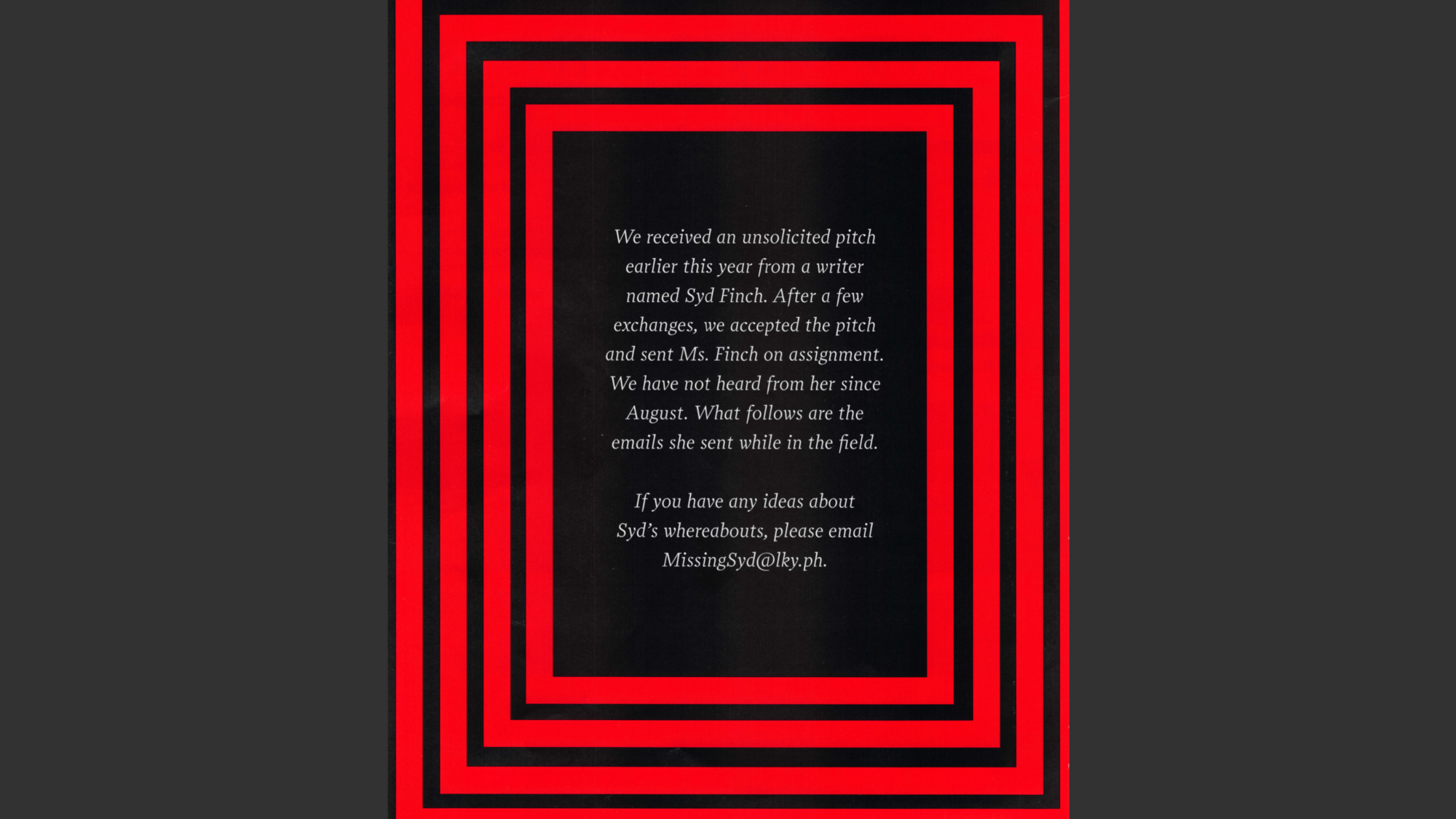

In the fall of 2012, the theme of the Lucky Peach was “Chinatown” and reading it I came across an article that set the hair on the back of my neck on end. It had all the bits that I find interesting when finding something to dig into for research. This mysterious article halfway through the magazine was called “The Mother of all Cuisine” and it began with this caveat:

(click on the image for full screen)

Then the article unfolded in what was really a quilt work of emails from Ms Finch to the editors of the magazine. The first few emails laid out a theory that certain dishes (pasta and tomato dishes really) were mastered and invented in Asia, rather than in Italy as many had thought; a theory I had come to like after personally experiencing pasta and tomato sauce in Xinjiang province China. I saw the use of tomato and pasta, all used in ways Europe had claimed as its own, and I was unsure of the origins and histories. Ms Finch claimed that she had heard tale of a chef who had been a stagiaire (an unpaid internship in the cooking world) at the top restaurants in the world, who had spent his late teens and early 20’s working with the greats, influencing them, and learning from them; that tomato sauce originated in Yunnan Province at the feet of the Himalaya, and that there was a Chinese antecedent to balsamic vinegar. All of this blowing the minds of the oral histories of European cuisine, an entrenched, white, male community. She writes “Gentlemen, there’s a Chinese cook passing through the best kitchens in the world, and I think he can lend support to a totally unconsidered rewrite of the way food traveled from the New World to the Old. I’m going to find him.” The Chef she was talking about is Yun Ye Su.

Yun is the descendent of some sort of exceptional culinary family. Not royalty, exactly; the family are either the originators or preservationists of a great trove of culinary knowledge and secrets. Yun’s childhood was spent in culinary apprenticeship, he had learned to tell edible plants from dangerous ones before he learned to speak. When he showed up in these European kitchens sometime in his late teens or early twenties—no one knew his exact age; he’d always worked without papers on a handshake agreement—he was light-years ahead of his peers. Of the chefs, too, probably.

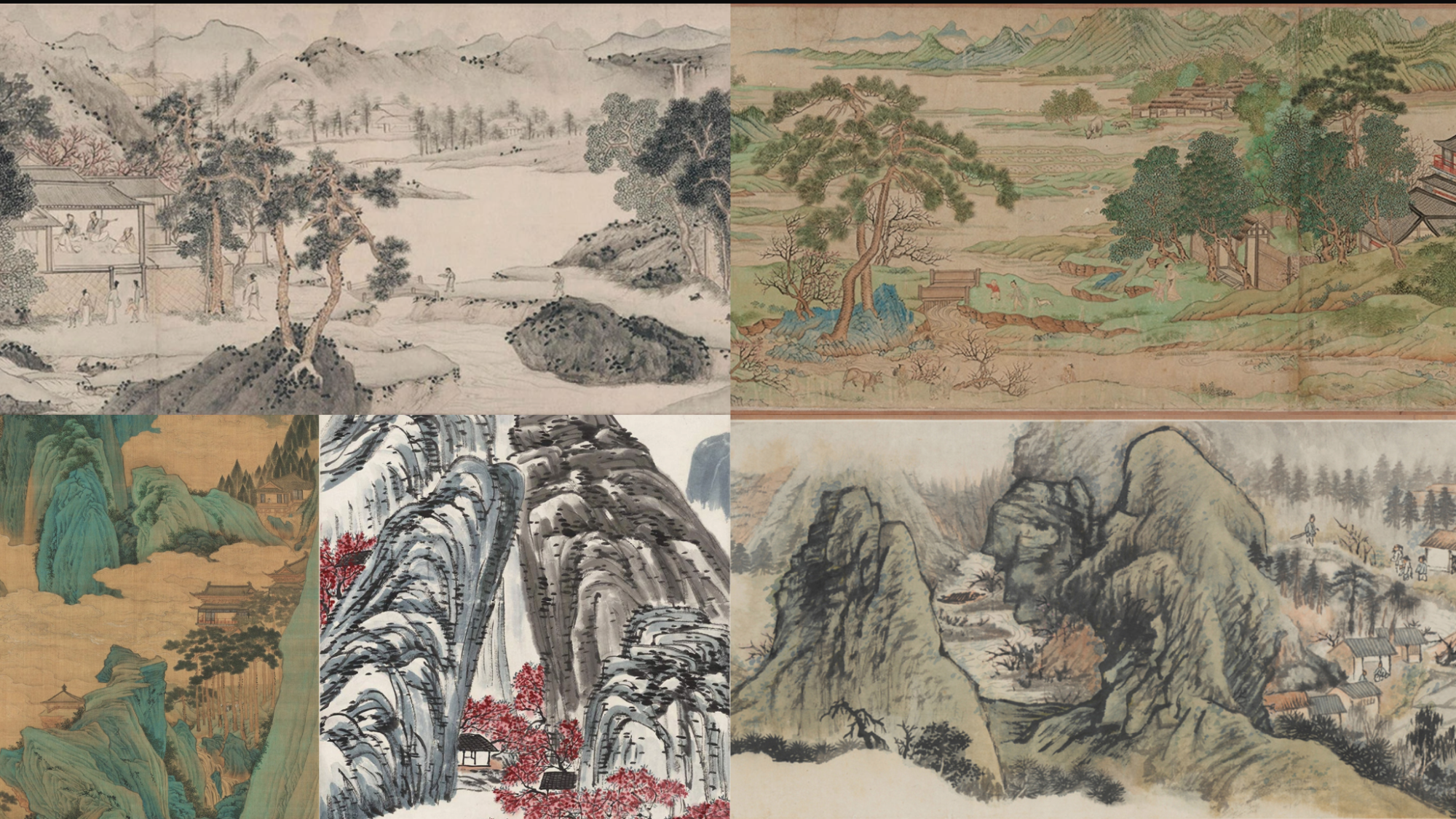

Yun was from Yunnan province, a magical place I had spent time in already, guiding cycling trips across Asia starting in 2003. There, the Himalayas peter out and the landscape folds like old skin. In the ancient worlds, river sources are sacred, and in Yunnan, some of the largest rivers of Asia watershed miles from each other with angelic peaks in between. It is where James Hilton stole the idea for Shangri-La in his book Lost Horizon. Hilton had read the accounts of eccentric botanist Joseph Rock whose articles in National Geographic magazine about magic oasis valleys in this part of the world, where plants and animals unheard of thrive, sparked a particular image in his mind.

Finch finds out about Yun’s restaurant through a slipped comment by Chef Massimo Bottura one late night at a MAD food camp in Copenhagen, that Yun has a place of his own, back in Yunnan. So off Finch goes to Dali, a village in western Yunnan, to find this culinary Shangri-La. She goes to Dali, spends weeks until word around town gets to Yun that Finch is there and looking for him, and he finds her. He invites her to dine at his house, in his kitchen. It is angelic, the descriptions of the meals layer culture and history, merging preconceived ideas of what dish was created where, making all obsolete and noise to the flavour of a good meal. Finch is then invited by Yun to go to a region outside of Dali where they can forage for ingredients, the home of his mother of all cuisine. And then, the article ends, Finch sends no more emails, goes quiet, unanswered, and the door is left wide open.

It was at this point that my heart started to race. I had been to Yunnan, I had spent days in Dali obsessing about food (the cured ham there is akin to Alan Benton’s Tennessee ham), I had seen things done with tomatoes that changed me, cheeses and fermented Tofu that shifted my palate outside of European and North American flavours for the first time and forever. And I knew that I was in a position and a place that I could, like Finch, fly to Yunnan and find Yun, in the hopes to be able to experience a meal and to work with Yun for future trips of mine. I also wanted to pick up what happened to Finch in the emails, why she had left off.

I reached out to the editors, I emailed the addresses left in the article, I asked guides I had worked with in Yunnan if they knew about this place and this chef.

I wrote out a budget, and a plan, and started reaching out to people I knew in Kunming, Lijiang, and Dali. I started putting out feelers to see if this secret restaurant was findable. Tickets were purchased, and plans were put in place. I had even started to mention this research trip to travellers I knew who might be interested. I was excited. And then I found Syd Finch, in a place I had not expected.

![]()

George Plimpton is one of those people, out there, like Forrest Gump, seemingly at all the crossroads of culture and a generation. He was with Hemingway in Cuba, he was with the Kennedy’s in Cape Cod (and some say he dated Jackie Onassis), he tried to stop the assassination of Robert Kennedy by grabbing Sirhan Sirhan in restraint, he founded the Paris Review with Peter Mattheisson (who set up the magazine as a cover for being a CIA spook), he was a backup quarterback for the Detroit Lions, he boxed with Archie Moore, he pitched in the Majors, played Basketball for the Celtics, he raced in the Mexico 1000, he flew on the flying trapeze, stood on the stage at the Apollo theatre on amateur night, acted with John Wayne, and was a percussionist under famed conductor Leonard Bernstein. George was a special kind of journalist and writer who wanted to experience things as an amateur in order to write about them in more depth rather than observe, to shake off the brace of the pen and feel the hit of a heavyweight punch in order to write about it more clearly. He was in “Good will Hunting” opposite Matt Damon as a psychiatrist. He also had a television show on ABC in the early 70’s. If you don’t know who he is, you have probably seen him before, he has always been there. He was a sports writer, but also a poet and an inspiration.

I was interested in Plimpton, as a fan of the Paris Review, and as a fan of experiential journalism. One evening, as my China research plans were being laid, I went down an internet rabbit hole and ended up reading article after article he wrote for various magazines and journals.

He was a gonzo journalist, and in the April 1985 issue of Sports Illustrated George Plimpton wrote about a pitcher he had found in spring training down in Florida. A pitcher who threw a baseball over 160 mph for the Mets, wore a heavy boot on one foot, spent his youth in Tibet, played the french horn, and was a practicing Buddhist with a largely unknown background. He had spent his early childhood in an orphanage in Leicester, England and was adopted by a foster parent, an eminent archaeologist, who was killed in an airplane crash while on an expedition in the Dhaulagiri mountain area of Nepal. At the time of the tragedy, he was in his last year at the Stowe School in Buckingham, England, from which he had been accepted into Harvard. Apparently, though, the boy decided to spend a year in the general area of the plane crash in the Himalayas (the plane was never actually found) before he returned to the West and entered Harvard in 1975.

In the spring of 1976, this lost soul withdrew from Harvard midterm and headed back to Tibet to study in a lamasery and learn how to harness an internal power and focus that would allow him to throw so fast.

It was all a Mets fan needed that year, after a long haul of needing a winning team, after the Brooklyn Dodgers fled New York for sunny San Diego, here was a saviour, to bring it all home. His name was Hayden Siddhartha Finch, and he was a fiction, made up, conjured out of the air by Plimpton as an April’s fool prank on Met’s fans and the masses. Sports Illustrated ran it for their April 1st edition, and it took off like wildfire. It was so successful that Plimpton wrote a book based on the character Sidd Finch.

This name was far too wonderful to be a coincidence; Sidd Finch the Mets pitcher and my missing Syd Finch, a Lucky Peach journalist.

My brain clicked and clanked and then the realization smashed in that, of course, David Chang, Peter Meehan, and Chis Yang were fans of sports writing; of course they knew of this classic April fools joke George Plimpton had played on Mets fans that April in 1985, and of course this new story in Lucky Peach, these emails, this new Syd Finch was too, a fiction.

What happened next was interesting; I knew I still had to go in search of something, that even though Yun Ye Su wasn’t, and that Lost Horizon and its Shangri-La were fabricated, these made me feel like I still had to go and explore this place. That something behind the ranges was lurking, something that inspired a feeling of utopia and perfection in these stories. I realized that the power of fiction was not fabricated, the leftover of a made up story has a very real mark; it affects. I was able to shake off a lot of preconceived notions of Yunnan because of this deception. I was able to go, with a cleaner slate, and realize that I might be able to see the place more for what it was rather than how it was presented.

A practical joke, a good one, maintains a careful ratio of deception and truth, and the truth left on the remains of my trip was that Yunnan province was a place worth digging deeper in. And how different was this practical joke’s false sense of reality, from any preconceived notion of place? Movies, stories, photos, have all changed the image one has of place before travel, and this has been the case long before George Plimpton thought up his Sidd Finch.

This is where stereotypes enter in. These preconceived notions affect the trip you go on. They change your expectations. Blarney Stones and leprechauns in Ireland, rice paddies in Vietnam, pasta in Italy, pubs and tweeds in England. The reality of the world is very different from these images though, and the world is not divided as once imagined. The cultural divisions that once were dramatic in the late 1800’s due to lack of communication and transportation, now are homogenized, and Saigon is a modern bustling city with Texas style BBQ and Italian style pizza, while New York has Bhutanese communities and restaurants. These are the abilities of the present day, and it is so much more interesting and rewarding than a fiction any ministry of tourism or instagram might try and convince you of.

I felt like, once I realized I had been tricked, that I had been freed, in a way, from part of my preconceived ideas of South-western China. Lucky Peach was playing with these ideas on purpose. It shook me up in the best of ways, and I felt it made it that much more important that I research correctly, and go back to Yunnan in person to look and feel what was there, what else had I fallen for, and what it actually is. I went, and it was to turn into a kaleidoscope of deceptions, fictions, realities, and reconstructions.

In between Laos and Tibet, two drastically different places and geographies, lies Yunnan Province. It is where south east Asia moves north into the rooftop of the world. This is one of those places where you can feel a transition of region happen in a few hours of travel, some sort of sea change. There are little clues that show the start of this tide, and it isn’t just regional idiosyncrasies, these clues are ideological, but if you blink you miss them. Small philosophical shifts show themselves through the minutia, through how we do daily chores, through how we treat domesticated animals, through how we produce art. There are tiny little signs that show themselves when on a long journey from one cultural zone to another, that can only really be seen by going through the motion of travel. Simply landing in a plane from some far away place allows for only the large shifts, but taking the time and pain of going step after step from point A to B one can feel the sands change under one’s feet. I went back with a route in mind in order to feel this shift, south to north through the cities of Dali, Lijiang, and Zhongdian.

Dali had been a centre of trade on an old route called the Tea and Horse trail, sometimes called the Southern Silk road. It connected Lhasa with Kolkata. Driving north from Dali to Lijiang you feel closer to the larger mountains. I had watched the old town here be demolished and rebuilt in the early 2000’s, always under construction. Now the project was finished and it was a prime example of the tourism rebirth of a city, somewhat more stale in character, shiny in commerce. Driving north from there to Zhongdian, crossing the Yangtze river, and entering the Tibetan Autonomous zone (the cultural boundaries of Tibet are more fluid than lines drawn in the map; in Yunnan there is a large chunk that was historically known as part of Kham, a Tibetan state that existed before the annexation of Tibet) you realize as you climb that you are now in the mountains rather than viewing them from the valley; the architecture shifts again, the climate changes, the language forms, the outfits, the beasts of burden all start to change. These three cities represent a triptych of trade routes, old trails as well as new ones. Now, there were new highways that made what once was a 10-hour journey just 2-hours. Things had changed, as they so often do, in Asia.

Ironically, in the cosmic growth that was happening in China in those years, the historic town centres of Yunnan’s triptych had all been re-built, not just Lijiang, and had been made new to look old, in a simple twist of fate, to look more like what was expected in the minds of tourists, and at the same time be functional for mass tourism. A staged theatrical platform, one that was hard to see as it was well hidden. Zhongdian had changed its name officially to Shangri-La, after winning a nationwide contest for the title from the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Lijiang old town looked more like an outdoor mall with its ancient small storefronts being replaced with new construction in the old style, to house mass produced products. And new highways and rail-lines had opened up Dali to the modern trade routes of T-shirts and silk scarfs. It wasn’t just for the sake of trinkets. Part of this new “Belt and Road” initiative had mapped an oil pipeline from Kunming through Dali, into Myanmar and down to the Indian Ocean. This was a byproduct of the new world order as written by Xi Jinping, China’s new leader.

There is an imposition that happens in travel, and it can’t really be helped, it’s part of what makes culture shock shocking, an imposition of definitions and ideas. In China I would often encounter this conundrum, the question of what preservation and history mean and to whom. The Han Chinese, the Naxi people of Yunnan, the Tibetan culture of Zhongdian, in this province where many cultures start to merge, there are different ideas of what is important to preserve and what isn’t.

The most preserved of the cities felt like Zhongdian, but even that, I discovered, was built new in the late 90’s. It felt antique, but in fact the town centre wasn’t 20 years old, it was oftentimes younger than the old-aged tourists coming to see it for its ancient-ness. It would soon burn down to the ground and again be rebuilt, months after my visit, with 65% of the town flattened in embers; to rise again from the ashes, new-to-look-old, this commoditized, state-endorsed faux Tibet, being built anew to be more ancient than ever before.

The aim of these rebuilds were with two tourist markets in mind: American and European ideals and dreams of Tibet and Himalaya, and domestic Han Chinese needs for entertainment and escape from the urban. Those two work against each other at times, the American-European market wanting a sense of the authentic and of spiritual escape, the domestic market wanting the feel of a theme park.

The reconstruction of all of these ancient towns made for a twilight zone patina, one that made the falseness of Yun Ye Su and Sidd Finch seem a little closer to reality, a little less false. Maybe it was the altitude but in this faux Shangri-La, realities merged and what was imagined seemed that much more possible. Perhaps this is what the lesson was: this region, this province had one limb firmly in the physical, and another floating in the lifestyle brand heavens of the new economies, a Himalayan Hollywood. It is why it inspires some sort of celluloid magic, utopian valley ideals, reaction myths of the mother of all cuisines, and professional baseball players that can pitch a fastball at 168 miles per hour.

But it would be easy to dismiss parts of Yunnan as inauthentic; that would be a mistake. After all, the rebuilding and renaming of cities, the theme park flattery of imitation is not new. Venice Beach California was initially a copy of Venice Italy, a real estate/tourism development, bought, sold, consumed. But it has become an authentic Venice Beach. New York was a new-to-look-old version of Amsterdam. Even Utopia was a conjuring. Written by Thomas More in 1516, Utopia was a novel trying to pass itself as a non-fiction travel book, the Greek word Utopia translating to “no-place”. To be honest, the vast majority of travel literature contains a recipe of deception, a cocktail of fiction and non-fiction passing itself of as biography; Herodotus’ histories were, in part, fabrications; Marco Polo’s accounts of his journey to China was not all truth; Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley were mostly entertainments of the pen; Bruce Chatwin was not alone in his isolated In Patagonia. To dismiss Dali, Lijiang, and Zhongdian as fakes would simplify a wonderfully human complexity; our want to make dreams reality. Our need to have Yun Ye Su, Sidd Finch, and Shangri-La to be real, even if they are only real as inventions. It is why fictional literature has value. It is not composed of facts, but there are truths contained within the narratives. To go to a place and understand what is there naturally, what was staged there commercially, what flows through there organically as well as synthetically, is complex, it takes effort, but it is that much more interesting, that much more rewarding.

There is an old poem called Peach Blossom Spring from the Jin Dynasty, 421 AD, that would be familiar to a domestic tourist of Yunnan. It is a story about a fisherman who follows a river to its source in the mountains, and discovers a crack in the mountain. He crawls through the earthen crack and finds a community living and not ageing in a playful utopian valley. He stays for a few days, then heads home and is warned that there is no use in telling people about this place, he will not find it again. He leaves markers, indicators, to make sure he can get back but days later when he tries to return, he cannot find the magic, the utopia is gone, or perhaps never existed in the first place.