With a voice like Caruso

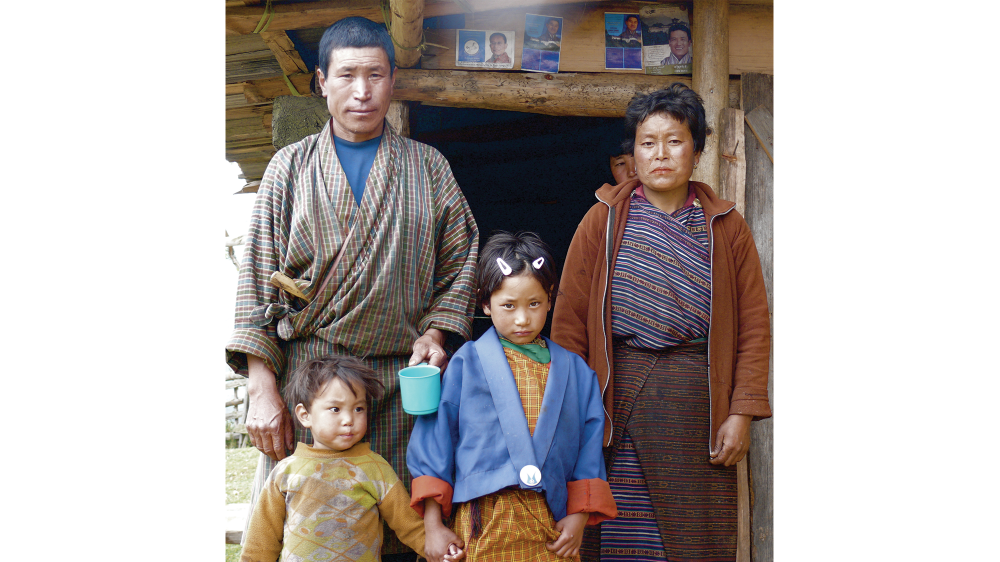

My friend Tandin was talking to me of dragons, concubines, drunken Himalayan gods, and ritualistic funerals. I was in Bhutan, two weeks prior to the first national election proposed by the King, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, and therefore for final few weeks it could claim to be the last Buddhist kingdom (on paper at least) in the grand and majestic Himalayas. The wise King decided that royal bloodlines get cloudy too often,and that it was time to look at other processes of leading the Mountain country of 600,000 souls. Tandin and I were hiking as much as we could of his homeland, searching for routes that would combine in a way that would minimize altitude sickness, and maximize objective experience through meeting locals and hiking through villages and vistas. He sang often, as I hung back, out of breath, choking on the thin air of 14,000 feet. Onward he trekked, singing in Dzongkha, the local language.

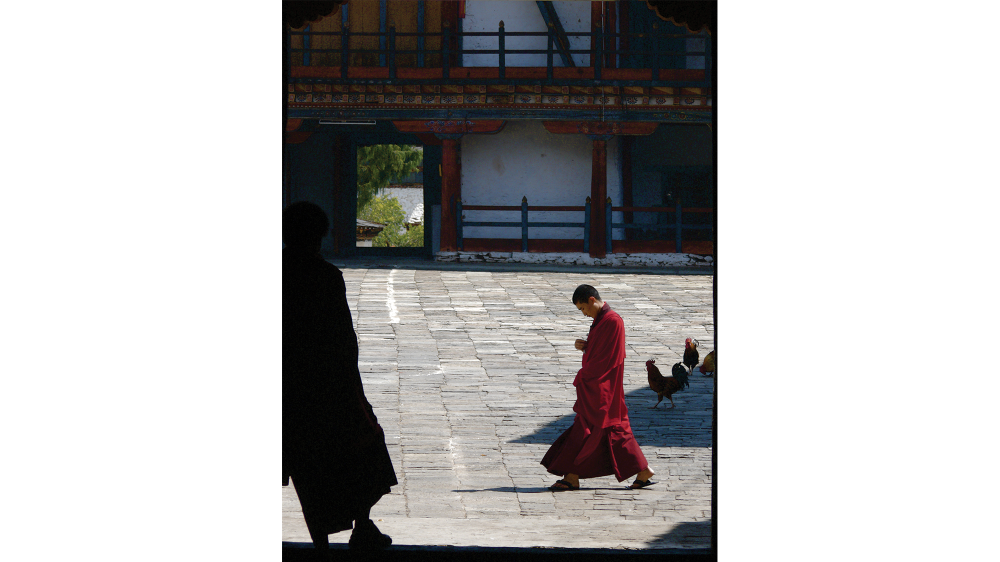

There is a set of laws in this county which were put in place in order to maximize happiness. Part of the rules are about arts and music, dictating that traditional songs must be kept alive. So the little kids all learn the ancient songs, what would be akin to us learning the poems of Homer, rather than reading the cliff notes.

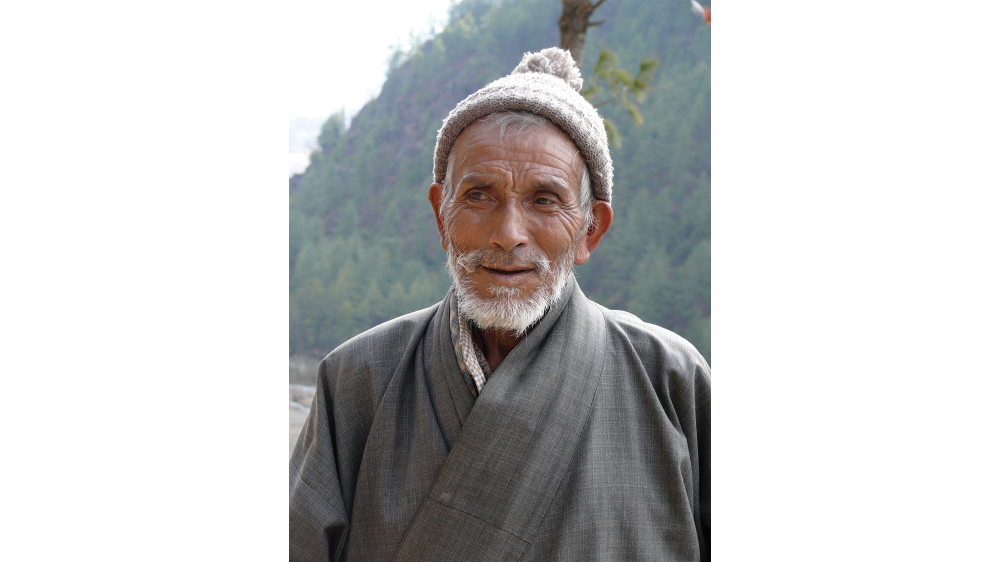

Tandin sang love songs, and said he was practicing for ‘Night hunting’, a local act which, once explained to me, opened up doors of perception about the way life must be lived in a place that is vertical rather than linear. A crow or arrow could fly seconds across a valley that is a full day of hiking to traverse. The relationship with land, and life, here is very different from anything I knew. I thought I knew about perspective on place and landscape, growing up in the country and living the city and feeling the changes that happen there. But there are two places out there in the coloured sections of the maps, where life is lived very differently from in all the peopled places; oceans and mountains. Here in Bhutan, we were stuck deep into the backside of the grandest chain on earth, and the way of life the flatlanders live is flipped upside down. Food and shelter change in the thin air, and crops and beast become a commodity in a more immediate way than in, say, the tropics. Red Rice grows at a slow pace for harvest, and Yaks become factories for all your needs. So you watch the rice, closely, and you follow the Yaks religiously.

This is why Tandin sang, he explained. His family had been divided into roles that were based on the importance of red rice and yaks. The men would follow the yak herds from valley to valley, lowland to high, depending on the season; and the women would watch the rice and make sure no critters or disease struck. Because of this, and the generally small populations, the concept of traditional husband and wife life was flexible. The Yak herders would be away for 6 months at a time living in far off hill sides, and each valley was sparsely populated so dating was no joke. Ain’t no Tinder in these hills. Because of all of this, love affairs would be allowed and encouraged, with stipulations. Thus was born “Night Hunting.”

If you were a yak herder, and whilst away from the family found fancy in a local girl of the valley you were herding in, you would indirectly ask her father when she was to watch the red rice field. Everyone in the family gets a turn so there was bound to be night coming up that she watches the field. Now, if the father approves of you, he tells you the correct night; if he doesn’t, then he tells you a night he is working and as you will see, it gets very embarrassing. So you know know the night she will watch the crop, and to watch the crop is a whole evening affair of sleeping in a lean-to and listening out for any deer or what-not. You then go to the field and stand a fair distance away from the hut. And you sing – you sing love songs, traditional ones, and you sing loud to attract. Like a cricket. If your voice is good, and if you were approved by the father, then you are allowed to sing closer over a slow period of time. And after about an hour of singing, or however long it takes to move in, you are allowed in for the evening to make love near the red rice field. The next day both parties would be off, and no strings attached. It is fleeting, and meant to be – it helps the valley’s blood they say. And should a child be produced, then her Uncle would take the child in, to be raised by the Uncles family and be known as a “love child” and generally not looked down upon as in western culture.

So Tandin would sing, and practice, and he had a beautiful voice, and seemed to be known well in the many valley’s we traveled through.

I asked if he had children in the valleys. And he smiled and stopped singing.

Tyler has wandered high and low, and sings a good song himself (though we’re not insinuating anything). Drop him a line if you like talking to a story-teller.