Arabic Calligraphy – A Tangible Culture

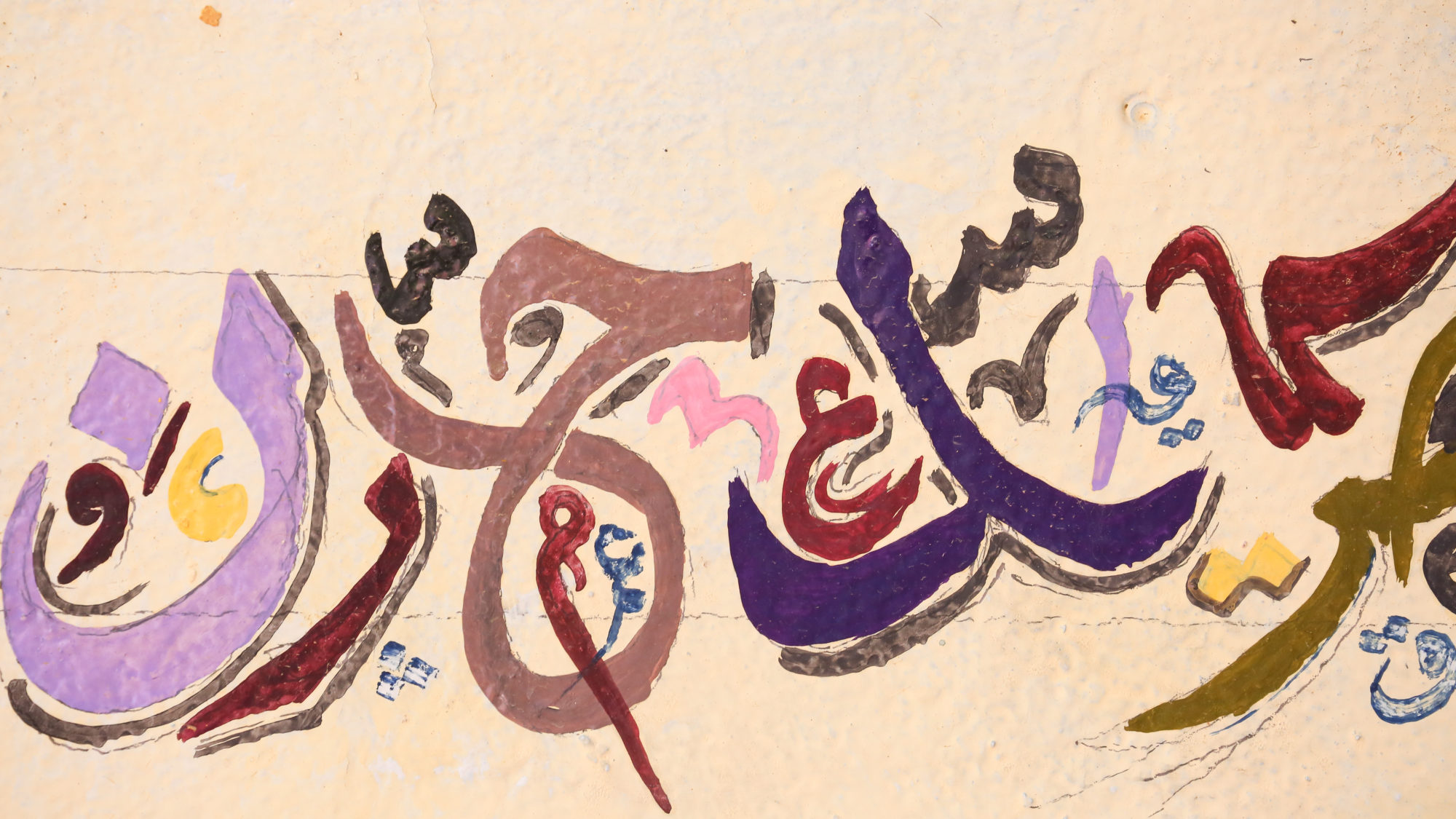

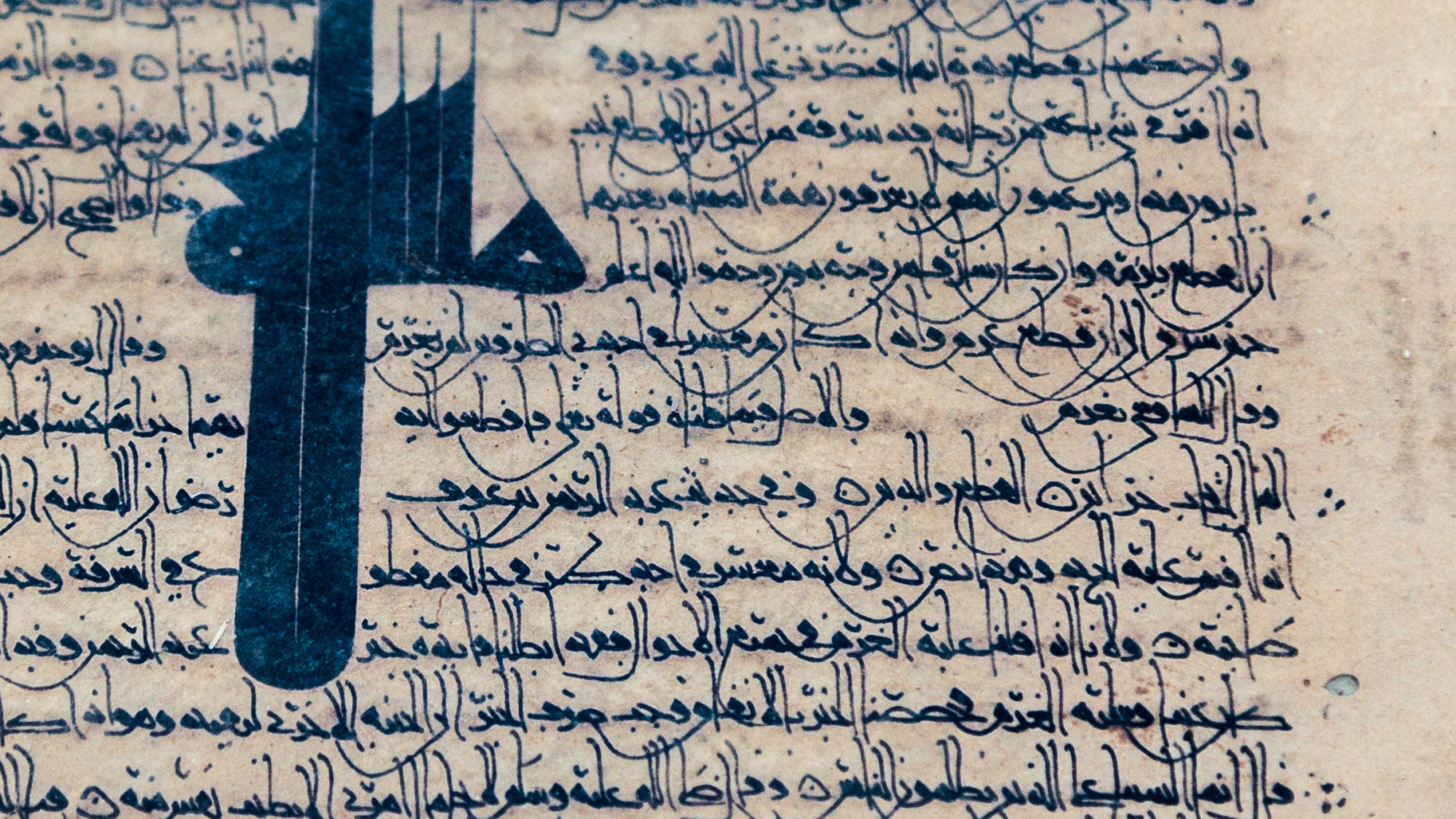

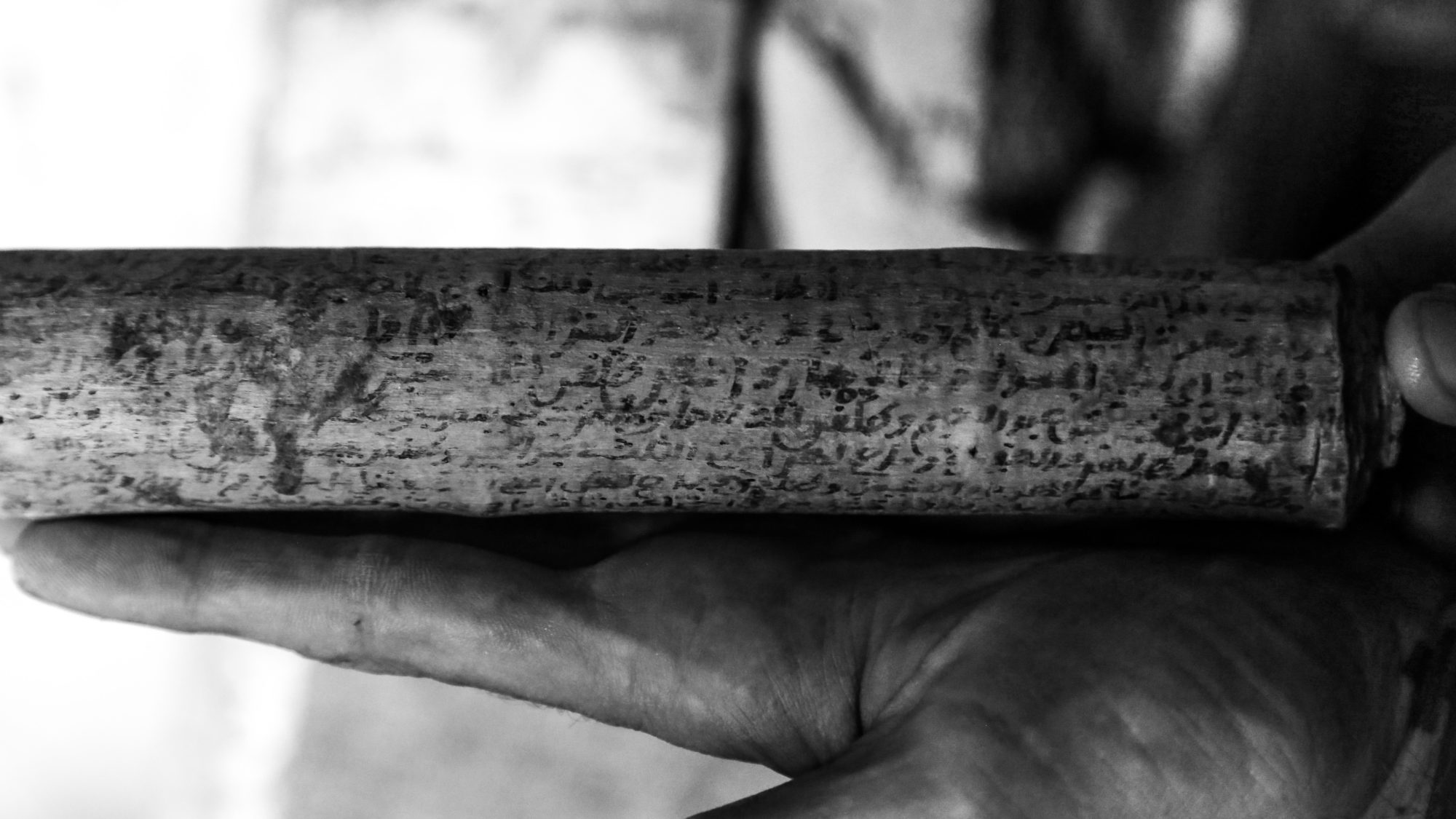

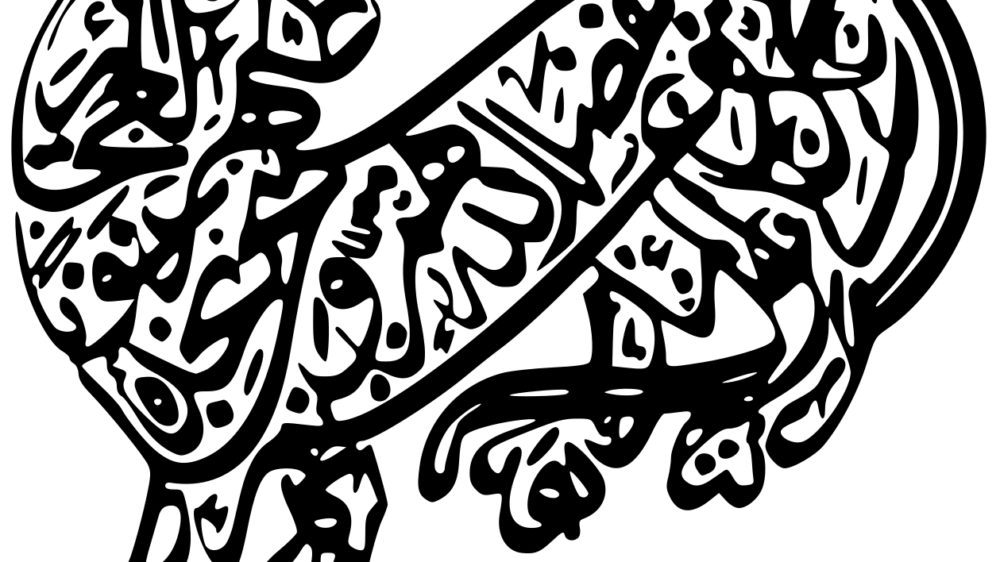

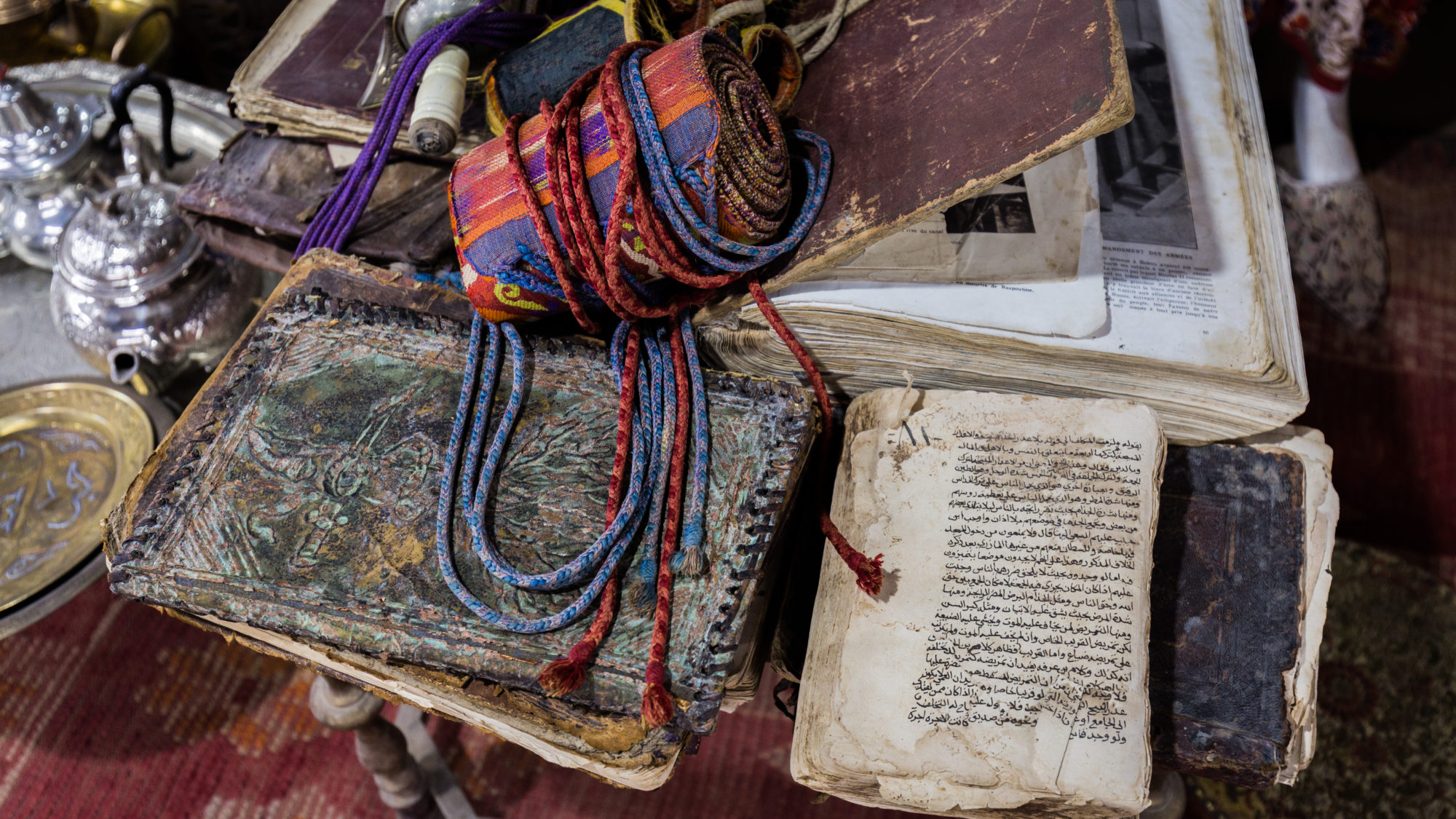

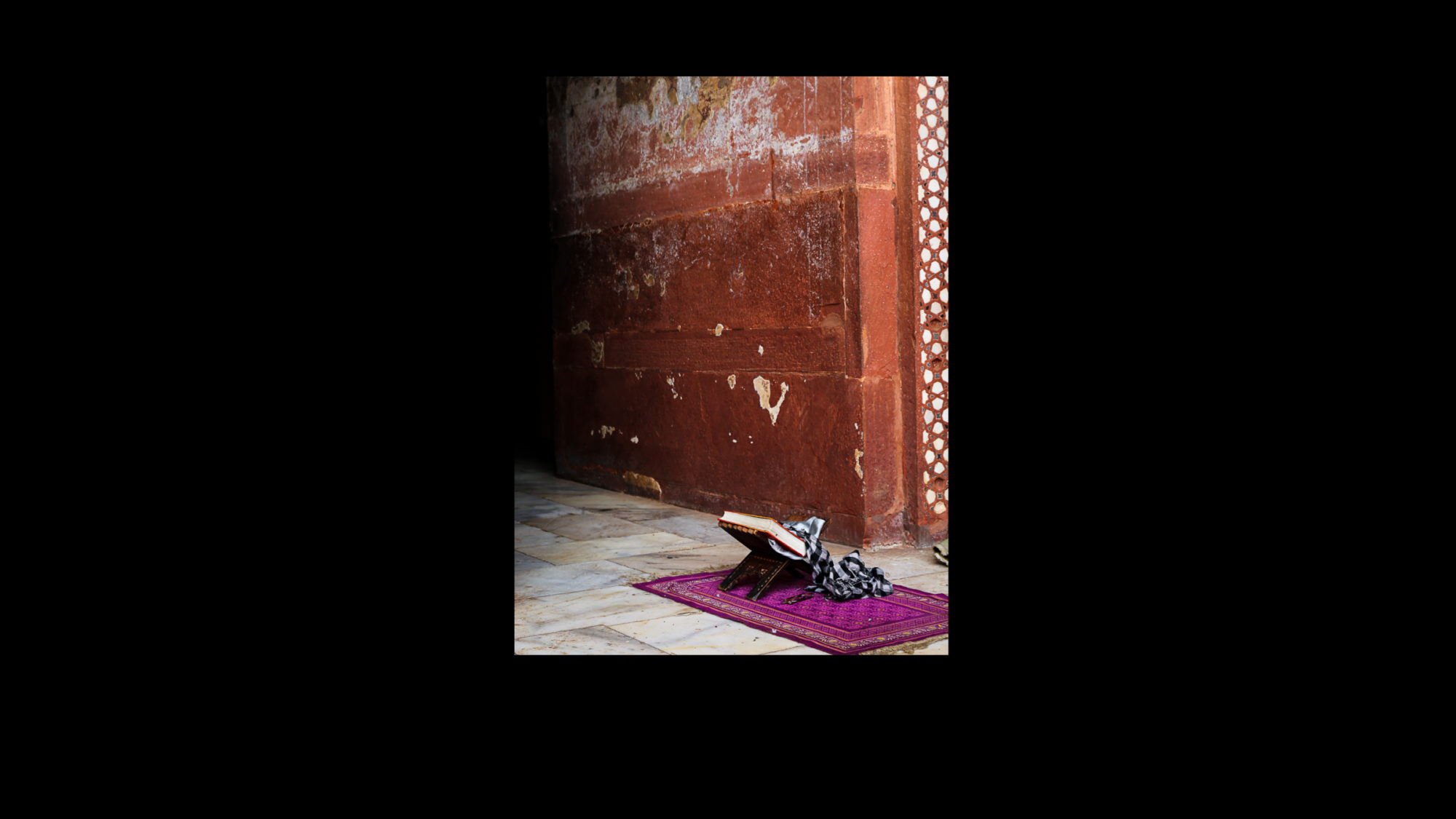

Arabic is spoken by about half a billion people around the world and is the language of the Islamic religion – from Jakharta to Casablanca, the reading of the Qu’ran and prayers are in Arabic. Muslims revere the Qu’ran as the literal word of God as recited to the Prophet Muhammad, so the written book is sacrosanct in Islam. The Arabic script has been used to write not only the Arabic language but among others Turkish, Farsi, Pashto and Urdu. It’s a language that is both secular and sacred, traditional, and ornamental. In a religion where figurative art was forbidden, Arabic calligraphy evolved to be the visual communication of a higher purpose, compelling the observer towards contemplation of the divine.

For purely secular reasons, I’ve been drawn to the language in its written form since before I ever stepped foot in Morocco where I live today, much in the same way as I imagine some foreigners feel drawn to the aesthetics of Japanese or Hindi. My first introduction to Classical Arabic script was not in the mosques and madrasas of Fez or Cairo, but rather the plaster inscriptions, mosaic tiles and wooden carvings, still remarkably preserved six centuries later, of the Muslim built Cathedral-Mosque of Cordoba or the Alhambra of Granada in Spain. The visual impact of a perplexing language so permanently embedded among dazzling examples of geometric art was an inflection point for me, awakening a love for the art of the written word, and sparking a curious itch to investigate further the culture responsible for these accomplishments.

It was therefore with great pleasure that I read that UNESCO declared this week Arabic calligraphy “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”. It’s a validation and a vindication of sorts. Validation of the aesthetic beauty of Arabic’s written form, a vindication of the misguided perception the “evils” that words written in Arabic invoke for some. That it now receives the highest praise for its contribution to immaterial human culture says much about its artistic merit and ability to awaken curiosity.

There’s a well known anecdote of Steve Jobs dropping out of Reed college in the 70’s but auditing what would be his most influential class, on calligraphy. He said, “I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science cannot capture.” His love of calligraphy influenced the design of the modern personal computer and brought a creativity hitherto unknown to the medium which revolutionized an entire industry.

Taking these first few days of 2022 to reflect on these confusing times, I think of what we can do as travel professionals to provoke a different way of seeing, what triggers do I have to offer to help others confront the baffling, and let the discomfort as well as the enlightenment in. The Arabic language, expressed as an art form, challenged me to expand my cultural horizons, and ultimately helped shape my world view. It reminds me of another quote of Jobs, when talking about innovation in the tech industry: “A lot of people haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.” My same thoughts and hopes for the future of travel.

Sebastian’s pen is mightier than the sword. If you don’t believe us, get in touch to get planning your next Iberian or Moroccan adventure.