In Cod We Trust

Some foods are so intrinsically tied to a place that often they shed a light on its past vicissitude much better than any museums or monuments. One of them is cod: the consumption of this fish is widespread across several continents, from Russia, to Western Africa, from the Caribbean to England, to the point that wars have been fought over it.

If you flip through the pages of Mark Kurlansky’s ‘Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World‘, the countries of Portugal, Spain, France, England, Norway, and Canada emerge as the main actors in the trade. But what about Italy? Not much is said in his volume, even though cod and stockfish recipes can be found pretty much all over the boot, from Genoa to Naples and from Livorno to Messina. I was born in a corner of the country where cod features heavily in the local cuisine, to the point of lending its name to a famous recipe – bacalà alla vicentina (more on this later). So, for Cod’s sake, I went down the rabbit hole of the cod epopee in the Venice area and, truth be told, found more questions than answers.

In the Name of Cod

The first Hamletic dilemma to untangle is one that lies at the very heart of the matter: when Venetians say ‘bacalà’, what do they mean? Always original, they go the opposite way to the rest of the country: ‘bacalà’ in the North-East of the peninsula is not salted cod, but rather stockfish, or dried cod. Why the mixup? Chances are that the Veneti were first introduced to salted cod with the name of bacalà and only later to stockfish, but since it’s the same fish, though preserved in a different way, the name stuck, becoming interchangeable. Ask a Venetian and she’ll tell you that indeed a stockfish by any other name would smell as sweet.

Cod Damn It!

The story that’s repeated locally over and over has all the elements of a disaster movie: a shipwreck, sailors adrift in the cold North Sea; death due to fatigue and starvation; a fortuitous yet deserted haven; and then, when all hope seems lost: salvation, also thanks to a portentous fish – cod, of course.

Since the dawn of its foundation, Venetians have had a penchant for good storytelling, no matter whether that required some sophistry. Crafting a myth, playing in the murky waters between facts and fiction, is no task for the faint of heart. When Venice needed a founding father, a man of their own, to explain how cod was popularized in the lagoon to the point of becoming its most famous food, that man they found: a champion of the aristocracy, an adventurer from one of the most eminent families in town. The legend is so deeply-seated within the locals’ system of belief, that you could pass for blasphemous if you dared to question it. Well, question it I did, and here’s what I found:

Cod is Great

November 5th, 1431. Venetian captain Pietro Querini is en route to Bruges, in Flanders, when a strong storm off the Isles of Scilly throws the ship off course. The wheel is damaged and the ship becomes unmanageable.

December 17th. Pietro and the crew abandon the ship in two life rafts. One of them disappears with 27 people on board.

Jan 6th, 1432. Pietro and 10 of the 42 men that were with him in the second life raft are stranded on a deserted skerry in the Lofoten islands in Norway. They survive on snails, worms, and the meat off a beached whale carcass. Only the accidental arrival of a ship from the nearby Røst island saves them. Recovered and welcomed in the main town, they admire how the locals eat a particular type of dried fish: stockfish. (According to another legend, the locals were very generous in sharing not just the fish, but also their wives with the newcomers, to the point that the dwellers of this archipelago are believed to have darker hair than the rest of the Norwegians due to the genetic inheritance, courtesy of the Venetians).

Spring, 1432. Piero & Co leave the island, carrying about 60 stockfish, which they use as trading material as they make their way back to Venice. Once back in the lagoon, he writes a pretty comprehensive report: his family belongs to the governing class so its influence is important, and the news spreads fast. But archival documents prove this story as apocryphal: he doesn’t bring any fish back with him, as the vulgata would want, nor did the stockfish catch on in Venice right away as a consequence of his writing. If anything, a dive in the Venetian archives will show that Venetians had been haunting the nordic waters for at least 150 year before Querini’s fabled trip and that Venetians, surrounded by waters rich in fish, preferred the fresh produce.

Cod Almighty

Another myth about cod in Italy says that its consumption increased after the Council of Trent (1545-63) imposed new dietary prescriptions, thanks to the writing of a Swedish prelate, Olaf Manson. But, according to historian Otello Fabris, this newfound penchant for a very stinky fish is best ascribed to famine, poverty, and pestilence.

For the Love of Cod

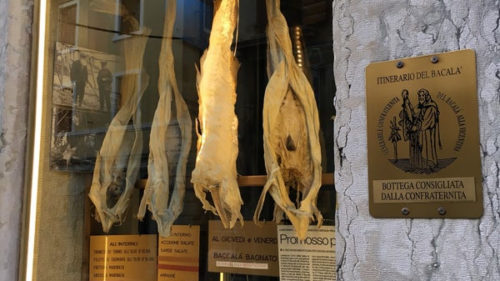

Cod is taken seriously in my neck of the woods. In my hometown, there is a shop that sells solely stockfish (and yes, you can smell it from miles away). Every year in September a two-week festival dedicated to cod takes place in Sandrigo, near Vicenza – a wonderful affair of polenta and juicy stockfish. And in 1987, a local lawyer founded a confraternity dedicated to preserving and spreading the ancient recipe of the bacalà alla vicentina, which masterfully blends together rehydrated stockfish, onions, salted sardines, grated Grana Padano, and a river of milk and extra virgin olive oil, in equal parts. Yum.

Cod Is Not Dead

Today, a Venetian family from Burano, the third generation of the Tagliapietra, keeps the tradition alive by importing stockfish from the Lofoten islands, following in the steps of Piero Querini, some 600 odd years before, but with a happy ending, as they supply such local food temples as Arrigo Cipriani’s Harry’s Bar. Now excuse me, but I need to find me some Cod.

If you share Lu’s belief in cod as an enigmatic yet unifying force without borders, or if you feel like challenging her on that, send her an email here.