The Lore of Folk Music in Canada

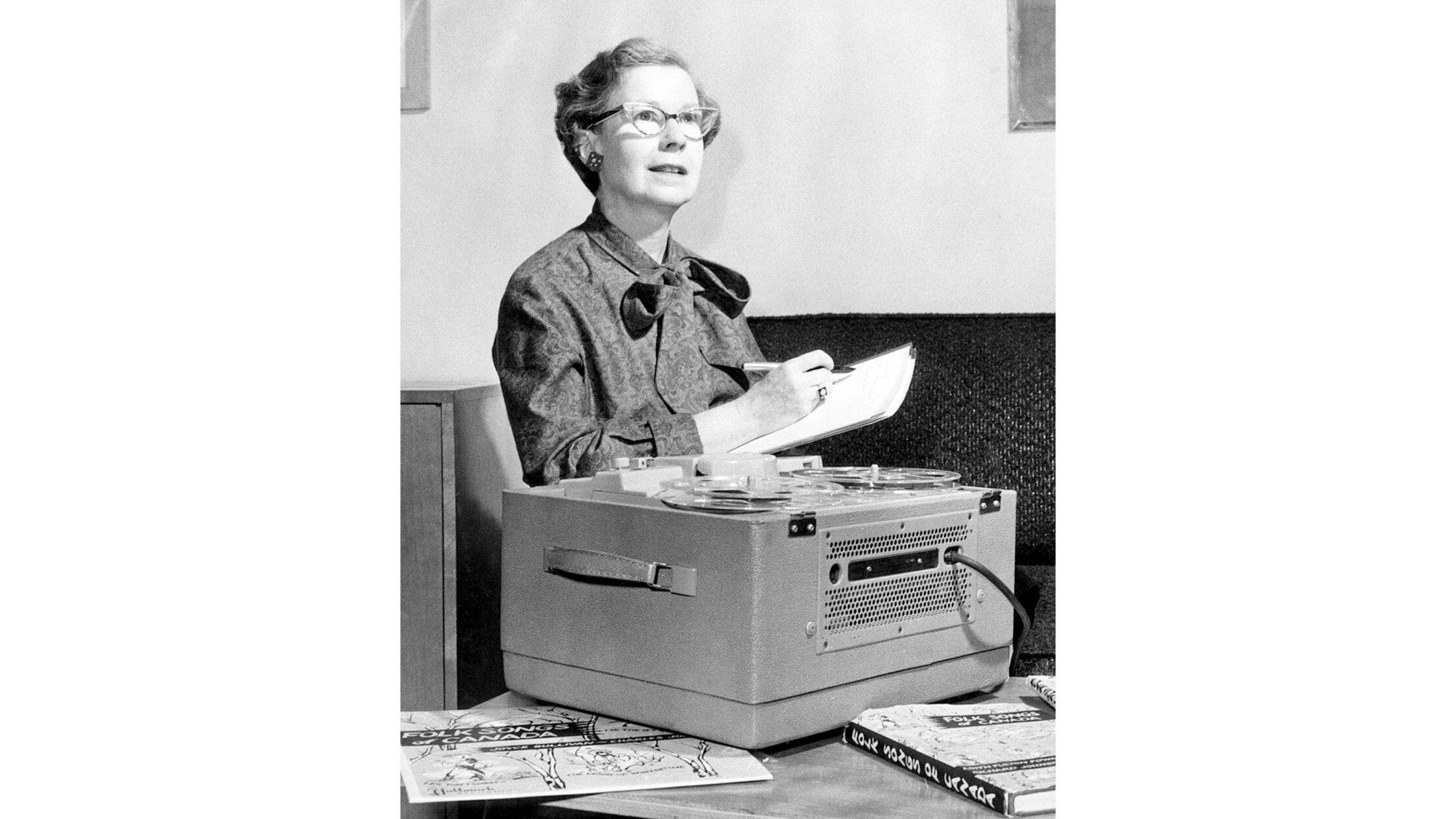

“On most spare weekends for the past seven years, Mrs. Fowke has loaded a portable tape recorder and a bottle of whisky (an essential ice-breaker) into her battered Peugeot and driven through the farmlands of southern and central Ontario hunting for old singers and older songs. She’s found plenty. Since 1957 she’s taped about a hundred wildly authentic folksingers and transcribed almost two thousand songs for posterity. A few months ago, in the village of Ballyfed, thirty miles outside Toronto, she unearthed one of those rare items that make purists shiver: a retired farmer named Fred Shorthill sang her a verse and chorus of The King and the Tinker that was last reported in 1855 in England.”

Maclean’s Magazine, December 1964

Ask a Canadian to define the country’s folk music today and you could be given about as many honest answers as there are Canadians. The answers might depend on one’s ancestry, influences or regional location – after all, Canada spans 10,000km between Pacific, Atlantic, Labrador and Arctic waters, between prairie lands, boreal forests and backwoods, between mountain meadows, tundra, rural hamlets and urban hubs, encompassing a myriad of cultures, first languages and personal histories. There is no one national nor universal way to define such a broad musical term as ‘folk’ in any country, let alone one so large. No one style or influence that can claim the genre as its own. Folk music, is the people’s music after all. It can be defined in as many ways as there are melodic expressions of the human experience in places lived, loved and lost. Like humanity itself, the music is redefined again and again within ever changing communities, traditions, migrations.

Before the turn of the 20th century in Canada, there wasn’t much ado about ‘traditional’ or older songs. The melodies just were. And they were passed along (or not) from generation to generation. Their survival was tightly bound to a reliance on oral history, not only in rural and remote areas, but also in urban centres which were becoming home to an increasing number of new Canadians. But as time progressed, and in the simplest of sums, a growing dependence on the printed word and on recording devices, both for learning and for fun, all meant that the need to recite poems and to make music by heart and hearth lost its practicality (though never its power). Enter Mrs. Fowke. Ironically these very tools of technology eventually helped preserve and share our folk musics at a time when memories no longer perpetuated them.

Edith was a Canadian folklorist (her name seemed to predestine her for the role), who hosted a radio show for the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) in the 1950s and 60s. She dedicated years of her life to seeking out living folk music across Canada, and to encouraging a national awareness of its existence. And though her worked touched on but a few strands of the musical tapestry that can be heard across this immense land, where many melodies are far older than the country itself, it helped open many ears and to engender a richer understanding of what is now rightly celebrated as a great cultural treasure trove: Canadian folk music.

On her weekly show, ‘Folk Song Time’, traditional tunes from the regions already known for their music were often played and expected by listeners, most notably from Canada’s Maritime provinces with their centuries-old ballads originating from Celtic ties to Scotland and France. There were also more contemporary songs written in those same Atlantic communities, stormy and sea-faring tales written in Canada that touched on the immediate surroundings and livelihoods of the singers. And from Québec, the woeful yet jig-inducing tell-alls of the coureurs des bois, or jovial call-and-answer songs that (quite literally) broke the ice among labourers in isolated logging camps.

Edith was convinced, however, that folk music had also been sustained over time west of Québec, in tiny unassuming folds and hamlets that didn’t even realize the treasures they held on to through song. That’s why she started focusing her research in Ontario. For this reason, she got in her car with the gigantic recording apparatus and an equally weighted amount of resolve and headed northeast from her Toronto home. It was the editor of the local paper in Peterborough County that sent her to a general store in a rural area nearby, where many immigrant families from Ireland had lived for close to a century-and-a-half at that time.

Now, the proprietors of this shop were always up for good conversation and before Edith knew it, the kettle was on for tea with her recorder taking up a good part of the table. Mary Towns (née Cleary) was soon happily singing some of her favourite old tunes for her, songs that she’d sung since childhood while doing the chores, or in her latter years running the post office. And she and her husband Bill also called over Mary’s father Mick, and then called up some of their country neighbours who were known to sing a capella at house gatherings over the years.

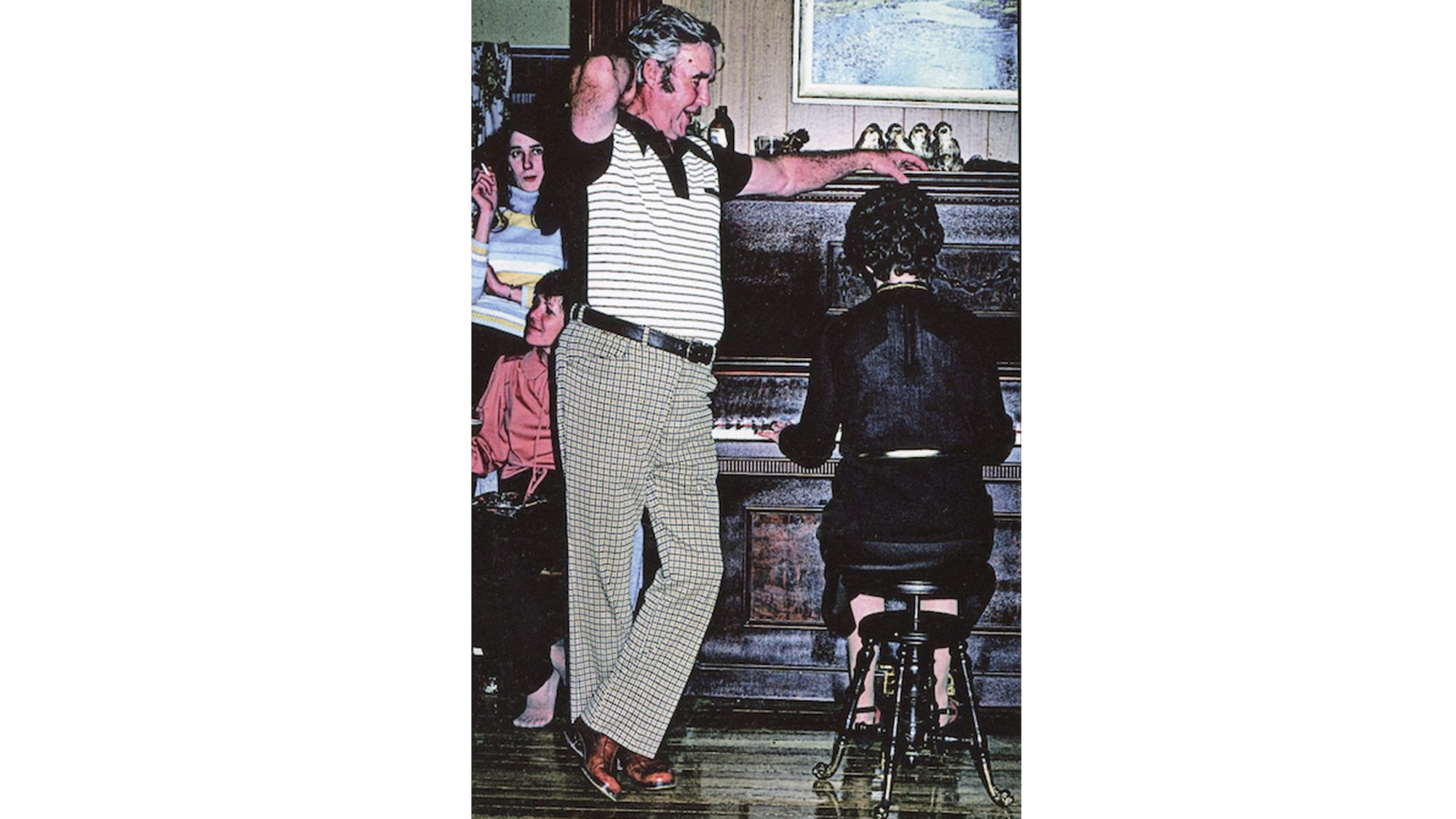

Mary and Bill were my grandparents, Mick my great-grandfather. And my father, Michael, to this day recalls fondly the visits that Edith made over several decades to the family store, to record music and to listen to their stories of the daily happenings in a provincial community General Store. With Edith’s encouragement, Grandma Towns even took a bit of time away from the family business to sing a tune in one of the side tents at the Mariposa Folk Festival.

I think about the songs and stories that my ancestors brought with them from the ‘old country’. It was the one thing they could carry with them in plenitude, that took up no room in their tiny trunks during a sixty-some day sea voyage ending near Québec City that continued by land to ‘Upper Canada’. How their interpretation of those ballads must have changed as their soundscape transformed drastically from what they knew: surrounded by cedar forests so dense they take the breath right out the wind, how resonation changes with snow on the ground, the calls of the wolf, and for many on arrival, the process of learning a second tongue, after their native Irish.

I can still feel the warmth in the living room of my childhood home on the winter nights when my parents hosted music parties. That house, over a century old, was once a tavern that provided shelter, a warm meal and no doubt some spirits for weary travellers making the trip from Toronto to Kingston, Belleville or Montreal. In our modern (for the times) living room, some songs played were as old as the hills, while others were playfully composed on the spot. Lots of ‘old time’ fiddle tunes from around Ontario, and from communities in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, along with ballads from Ireland, clogs, jigs and reels, and even Gordon Lightfoot and Joni Mitchell found their way in to the mix by midnight. For the musicians crammed into that old house, a good tune was simply a good tune, and the important thing was to share it well. Those old pine floors beneath us danced as much from the instruments, voices and waltzing as they did from the heels of musicians and listeners that kept time. My legs were not yet long enough to reach those floor boards, but I could feel their vibrations right through the chesterfield. Ah, the joy of social gatherings in your pyjamas with your bed just steps away. And no one to blame you if you fall asleep mid-tune, lulled by the ballads of past and present.

In this tiny region within what today we call Canada, mine is but one perspective of life put to music.

From East to West – Folk Music Festivals in Eastern Canada to weave into your travels:

Newfoundland & Labrador Folk Festival (July/August)

Celtic Colours International Festival, Cape Breton Island Nova Scotia(October)

Mondial de L’Accordéon, Montmagmy Québec (September)

La Grande Rencontre Trad Festival, Montreal Québec (September)

Bobcaygeon Fiddle & Stepdance Contest, Bobcaygeon Ontario (July)

Curve Lake Pow Wow, Curve Lake Ontario (September)

Greenbridge Celtic Folk Fest, Keen Ontario (August)

Mariposa Folk Festival, Orillia Ontario (July)

Celtic Roots Festival, Goderich Ontario (August)

Canadian Folk Music Awards, rotating locations (April)