The Pig Side of the Moon

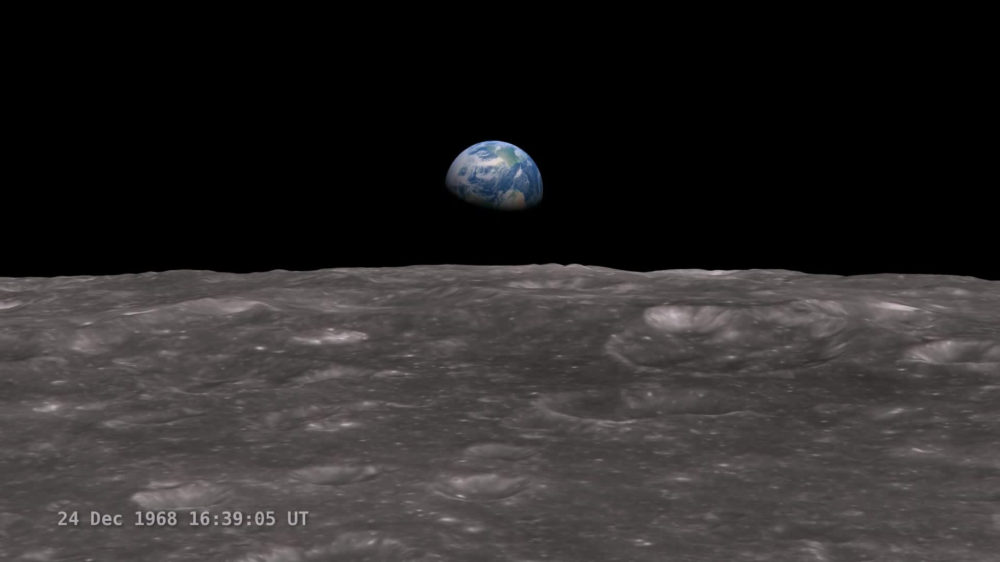

July 21, 1969. My parents were traveling to Spain on their honeymoon, racing their tiny, overpacked Fiat 500 convertible beyond the laws of physics. They pulled over at a cafe in Tossa de Mar, a Medieval town in Catalonia, hastily parking the car on the sidewalk. It was very early in the morning (or very late at night, depending on how you want to slice it), yet tons of people were gathering around TV screens, or had their ears glued to radios, 600 million people around the planet holding their breath. They managed to elbow their way to a decent viewing spot to catch NASA’s grainy yet powerful images: Neil Armstrong’s left foot stomped on the powdery lunar surface, and his voice, coming from thousands of miles over our planet, crackled: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind”.

Back on Earth, a collective liberating sigh of relief erupted inside that Spanish cafe. Perfect strangers hugged in uncontrollable jubilation, pondering the profundity of what they had just witnessed. Curiously, it was also thanks to a group of 21 Spaniards who worked at two of NASA’s space monitoring stations in the mountains outside of Madrid that all of this was possible to behold.

The stars hadn’t aligned yet for me to be born then, but I’ve heard my mom recount that story a thousand times with watery eyes. Her narration is certainly wrapped in a sense of awe because of the occasion itself, and because she had just tied the knot. Or maybe it’s because of the several cavas she and my dad had been knocking down the night before. Be that as it may, perhaps this is the origin of my fascination with space.

Fast-forward 51 years, and for the first time in history, we now have footage of a rover’s wheels touching down on Mars. It’s not the first time astrophysicists have successfully managed to land a robotic, unmanned spacecraft on the surface of the red planet. But what’s special once again is that we have eyes on it, actual real-time moving images and sound! This time, it was my turn to be glued to the TV screen. The high-quality images and the secret message encrypted in NASA’s Perseverance rover’s white-and-red striped parachute (written in binary code and translating to “Dare Mighty Things”) almost made it feel like a sci-fi movie. And if that weren’t enough, NASA has been announcing quite a series of extraterrestrial firsts over the past weeks: not only did it succeed in flying a powered, controlled helicopter – called Ingenuity – on Mars, but it also extracted breathable oxygen from carbon dioxide from the red planet’s atmosphere. Talk about pulling something extraordinary out of thin air…

When the lunar module landed in the summer of 1969, with only 30 seconds of fuel remaining, NASA (and the world) had to rely only on radio communication. Armstrong’s words — “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed” — must have felt like the stuff of dreams. He later confirmed that landing was indeed his biggest concern, because “the unknowns were rampant”. Yet, even with half a century in between the two missions, there’s still the same level of obsessive precision, each maneuver tried and tested countless times and calibrated to withstand any foreseeable glitch, with the possibility of a death plunge always lurking in the dark abyss around them.

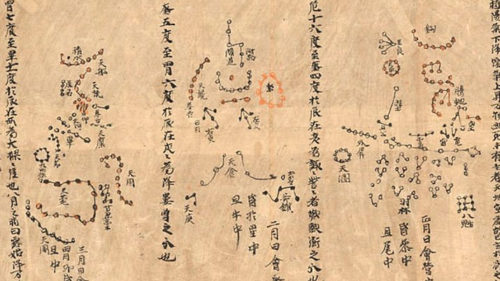

For millennia, mankind has been looking at the sky, trying to decode its pattern, in order to get a sense of direction, meaning, and inspiration, from China to Mexico, and from Egypt to India. Often at great risk. Heck, in 1615 Galileo was tried by the Inquisition for heresy, and forced to recant his belief in heliocentrism. Ironic how history goes sometimes: a century later he was already celebrated as a hero and martyr of science. Even the middle finger of his right hand was collected and preserved as a relic for worship (today housed at the Galileo Museum in Florence). Space has claimed many lives – astronauts, cosmonauts, physicists, civilians, monkeys, dogs, cats, mice… even a guinea pig. Eager to answer the haunting question “Are we alone in this vast cosmic ocean?”, or as Pink Floyd would put it “Is anybody out there?”, we’ve launched an array of instrumentation into space, from rockets to shuttles, from satellites to telescopes and space probes. We’ve even sent some ‘messages in a bottle’ in the form of the Voyager Golden Records, time capsules intended to inform any intelligent extraterrestrial life form of the diversity of life on the planet we call home (listen to a sample here and to the most recent episode of our own WPIG here).

Since Yuri Gagarin, the first man to successfully venture in outer space in 1961 (the 60th anniversary of his pioneering mission just passed), the universe seems to have become much more reachable, even though it’s been expanding ever since the Big Bang some 13.7 billion years ago. And this is just the beginning of space exploration. We’re talking about unfathomable distances, in time and space, that are hard to comprehend on a human scale. Yet, space travel for recreational purposes these days seems to be on the horizon. Need a change of scenery? For a mere $52million per person you can already buy a ride to the International Space Station on Elon Musk’s SpaceX spacecraft. Keen on waking up to a different sunrise and be floating in an unusual weightless atmosphere? The first cruise ship-style space hotel is scheduled to open in 2027.

All of the above, however, has also highlighted how minuscule we are in the grand scheme of things. And while we are stretching the boundaries of our knowledge, there’s still an incredible number of unknowns and uncertainties, mysteries that keep escaping us and keep us on our toes. In the depths of the Gran Sasso mountains in Abruzzo, in Central Italy, a team of 170 scientists is searching for the most elusive, controversial and purely theoretical substance that’s supposed to make up 85% of the physical universe: dark matter. Should they succeed, it will be another giant leap for mankind.

Man’s fascination with space runs so deep that all these missions have left many profound marks in our culture at large, with a plethora of photos, movies, songs, books, essays, artworks, and conspiracy theories invading our little blue planet.

So while space tourism is so imminent, yet still a few years away, here’s a disorderly sample of space-inspired tracks, movies, and books. It’s not all-encompassing, but it spans from the classics to the experimental. There’s some travel and some tripping; you’re in for a hell of a ride into the cosmic deep to the piggy side of the Moon — like a nouveau Michael Collins, the so-called third man on the Moon (who just passed away), although he never step foot on the lunar surface, despite being so close, but got to see its dark hemisphere. So take your protein pills, put your helmet on…

Read:

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, by Douglas Adams; Solaris, by Stanisław Lem; Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, by Carl Sagan; If the Sun Dies, by Oriana Fallaci; From the Earth to the Moon, by Jules Verne; Carrying the Fire, by Michael Collins

Watch:

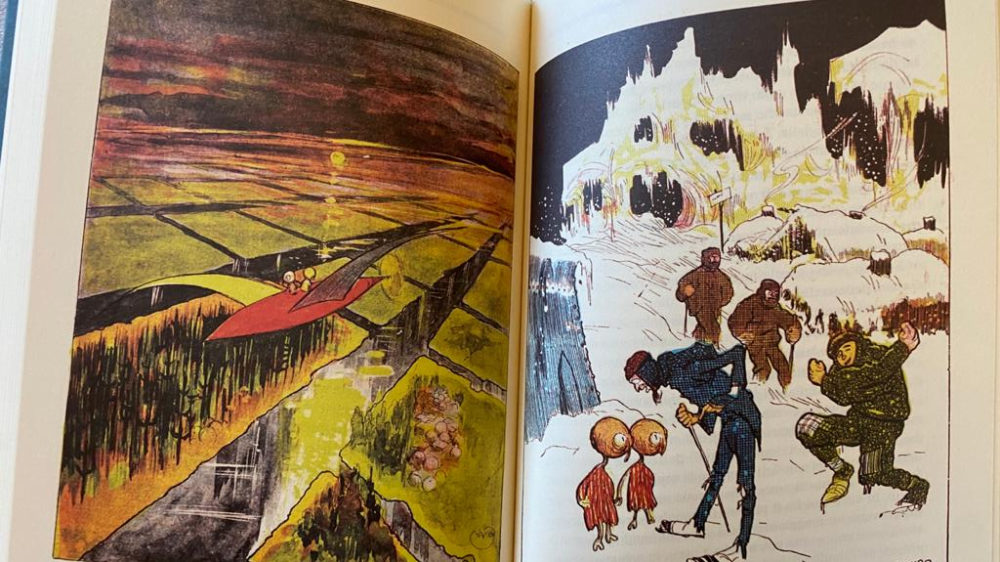

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, by Steven Spielberg; Interstellar, by Christopher Nolan; First Man, by Damien Chazelle; Ad Astra by James Gray; 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Stanley Kubrick; Planet of the Apes, by Franklin J. Schaffner; Arrival, by Denis Villeneuve; Apollo 11, by Todd Douglas Miller; Apollo 13, by Ron Howard; A Trip to the Moon, by Georges Méliès; The Martian, by Ridley Scott; Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, presented by Carl Sagan; Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson; Rick and Morty, by Justin Roiland and Dan Harmon; The Midnight Gospel, by Pendleton Ward and Duncan Trussell.

Listen:

Lu’s head might be in the stars, but her hooves are still solidly grounded on planet Earth. Shoot her a note here with all sorts of ideas, both celestial and earthling.