The New Colossus

I spent a lot of time in China in the early 2000’s, trying to make up for an overly euro-centric upbringing. I knew there was a world I’d overlooked, and hadn’t been taught about in school, a missing hemisphere. I’d read books like Ernst Gombrich’s History of Art which ignored the “East” side of the globe, attended the University of Georgia’s Philosophy department which had no eastern philosophy program…. Faced with the choice of German or Greek or the woods, I picked Greek and studied Aristotle. But when my formal education finished, I ran to the missing parts on the map to find out what was there.

First I lived in Taiwan for a bit, then got a job in southern China and stayed there for the better part of 7 years, before heading to Peru and Ireland (other blank parts of my map). My relationship with China has been complicated – there is fascination and curiosity, frustration and confusion, and plenty that I still don’t understand. So I have spent more time in my adult life working on the puzzle that is China than any other place.

As the pandemic started to really unfold in late Spring last year, I dove deep back into my history books for comfort, immersing myself in late 19th and early 20th century China. I was enjoying travelling to a time and place that felt far away from my confined, restrained lock-down existence at home. Until something I read jumped right out of the page, through space and time, and landed smack dab in my very neighbourhood in the east end of Toronto.

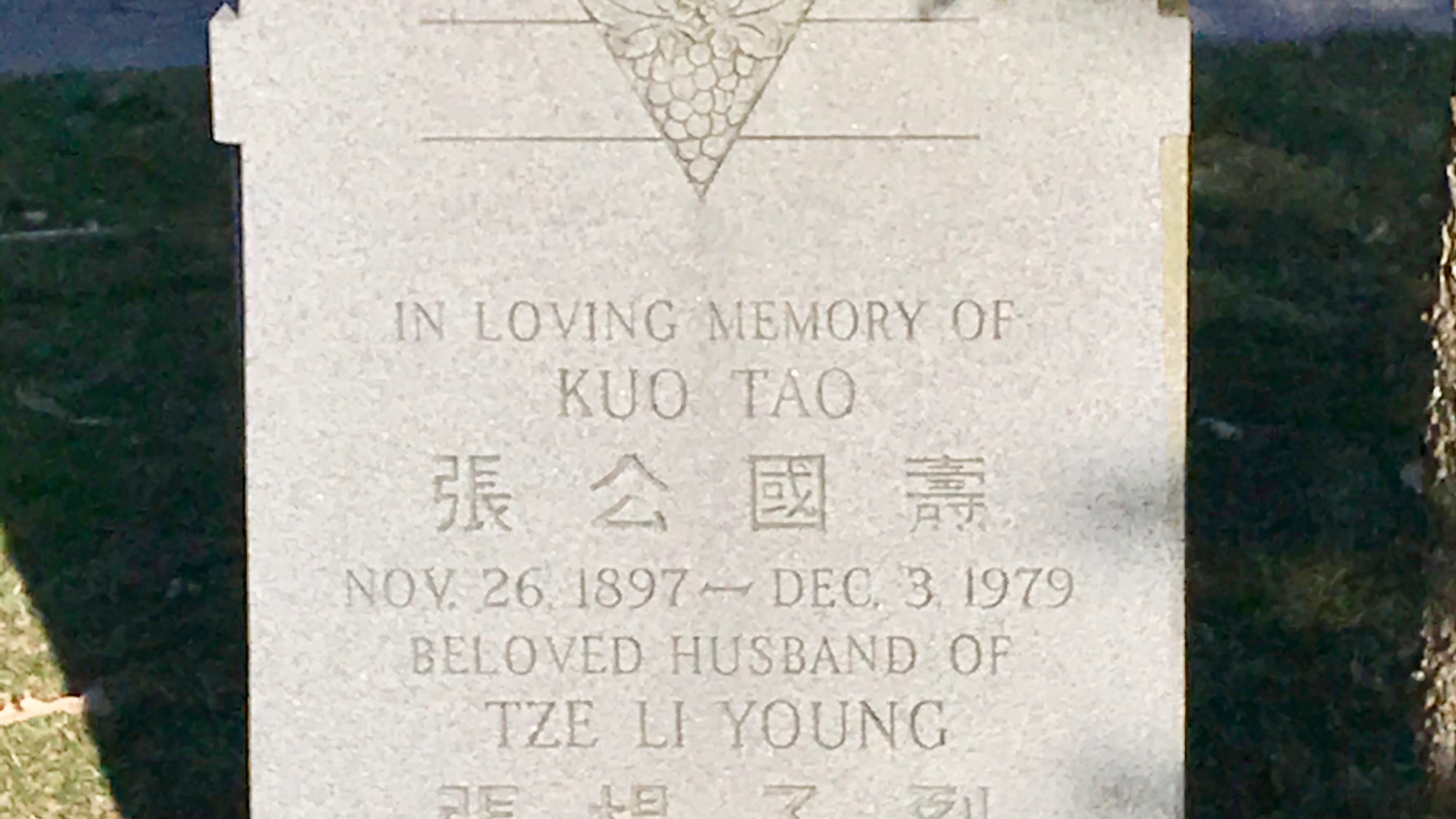

Among the stories and travelogues of Chinese history I noticed a name, Zhang Guotao (also spelled Chang Kuo Tao), who was with Mao Zedong and the group that started the Communist Party of China. Zhang Guotao ran the show for a number of years, and during the ‘long march’, the name given to the period of time where the communist party was on the lamb from the Kuomintang (Nationalists), he and Mao had a power struggle and went their separate ways. For Mao that meant founding the People’s Republic of China and becoming the principle actor in the country’s 20th century development. For Zhang that meant living in Hong Kong for a while, and then moving to Toronto and disappearing into the diaspora.

In one of the books I found his grave details and realized it was a short bike ride from my quarantined house.

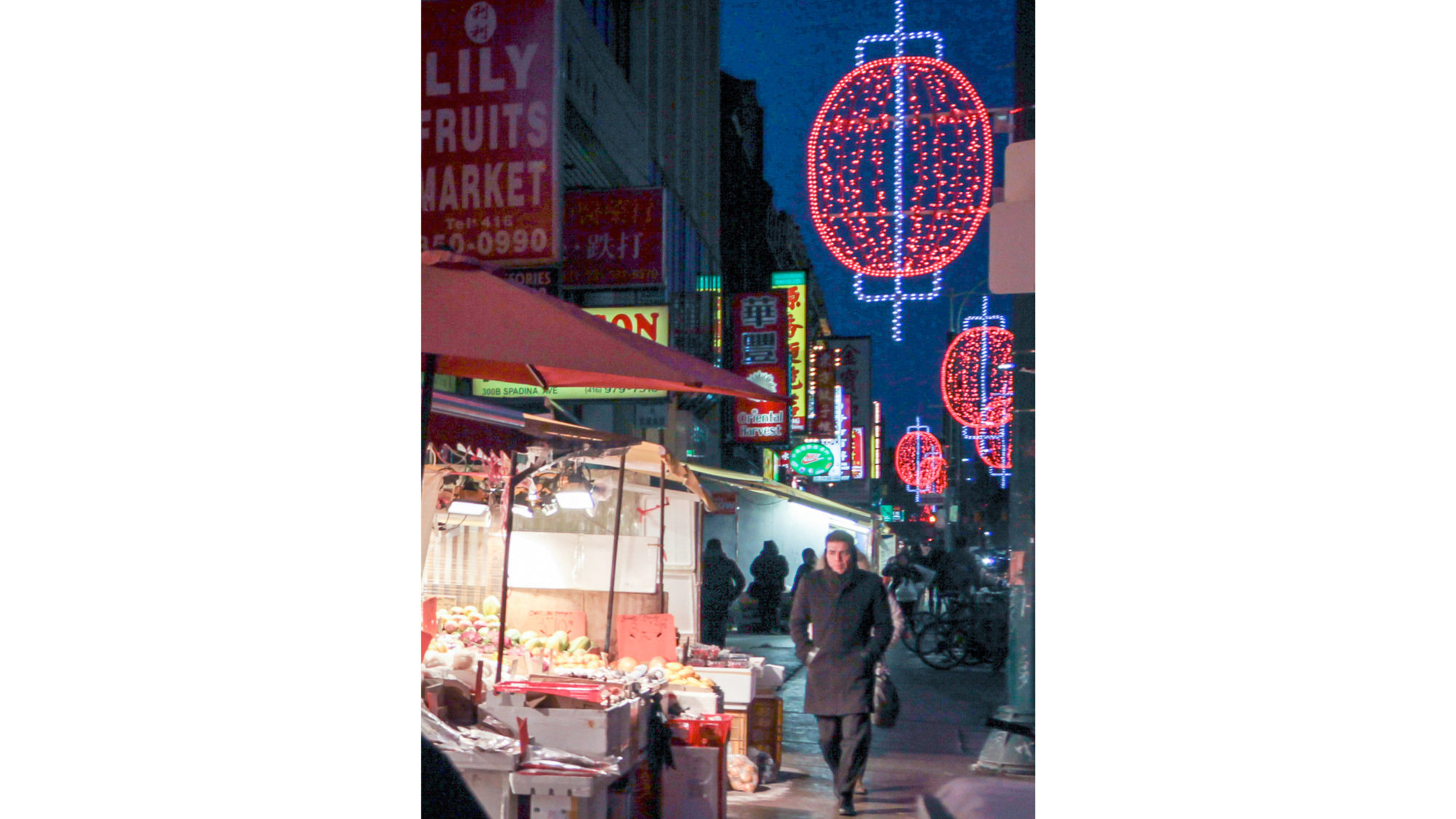

There are some cities that achieve such a cultural complexity that they transcend the country they are in, and fundamentally change character, joining that strange collection of cities around the world that are truly global. New York comes to mind, Shanghai is another, London an obvious example. Toronto is the quiet giant in the club, with more immigrants than any of those other cities. And I don’t mean that in a cute PR campaign sort of way; 52% of the population of Toronto were born outside of Canada. To put it differently, most people here are not “from” here, which creates a unique culture of Toronto, as a place that is constantly being written, a place full of many places.

Immigration has always happened and culture has always been more portable than one might imagine, being carried across oceans to mix with other cultures and make something hybrid or something new. No place is entirely static. But these days we can carry culture with us, we can re-invent it, recreate it, mold it, form it and move into it with incredible speed and ease – and in enormous numbers. In these cities that transcend their geography, this movement becomes a defining feature, and it frees up the occupants to interact with, create, indulge and reinvent their cultures in new ways. There is freedom in this movement. It could be freedom from something not wanted, like a past history to run from; or it could be the freedom of an empty canvas just to become something different; or, perhaps, a freedom from place.

Closing the book, I jumped on my bike and I rode to a graveyard I had never known to exist or visited before, and walked around clad in spandex until I found a grave, and gazed upon it, as if to know the life of a person through looking at a stone submerged in the earth. I am not praising or damning Zhang Gutao – I don’t know enough about him and his life to judge. but what I was seeking was a proximity, a synchronicity with a distant time and a closeness to a place half a world away. It felt like magic to be able to feel the connection of time and space.

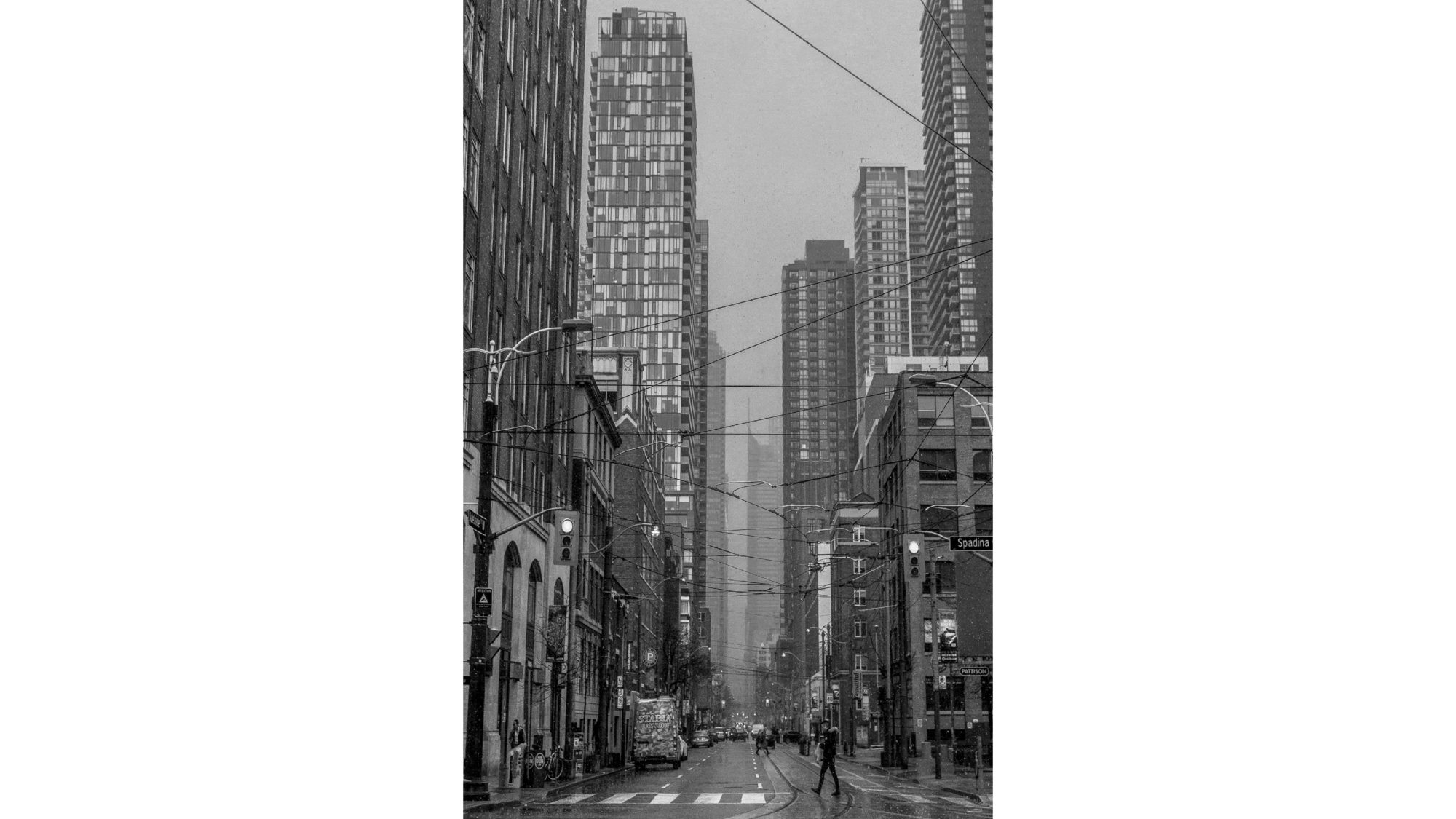

My reaction to seeing that grave was very much affected by my feelings about Toronto, as a ‘place’ made up of so many other ‘places’ and a place that supports and welcomes and includes. I thought about my own work as a specialist in planning trips to different parts of the world, and about how we love to jump on a plane and fly far away to interact with a people and a culture – a ‘place’ – in a way that so often ignores the existence of those places in our own cities. There is plenty of Lijang, London, Lisbon and Lagos in pockets of our own cities if we take the time to explore. I want to get better at this, at seeing this mobile kaleidoscope in the world, in my city, and I am fortunate that Toronto provides the atmosphere to allow it so easily. The city is a gathering place on the banks of a great lake that brings people and places like Ethiopia, or Vietnam, or Portugal, or China to exist in some small amount right here, to reinvent themselves, and to reinvent the city.

Toronto does this by history and by accident but also now deliberately and intentionally, and has been planned to be a gathering place, opening its soul to be reinvented by the people who come here. The traditional territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples, the city’s past and present has it’s problems and complexities. But there is also a particular magic to this town which transports and delights me, and I feel lucky to be warped from country to country just by pedalling the two wheels of my bike from street to street, my trace on the map writing a love letter to a city that is unique, a community of multitudes.

*The New Colossus: In 1883 Emma Lazurus wrote a poem titled “The New Colossus”. It was for a competition intended to raise money to build a pedestal at the foot of the new statue in New York named “Liberty Enlightening the World”. Emma was born in New York to a family who were Portuguese refugees from a settlement in Brazil. She wrote comparing the new statue to the Colossus of Rhodes, a beacon of hope for the diaspora. Toronto might not have a statue of liberty, but it has the idea and spirit of this poem, well worth a gander and you can link to it here.