X Marks the Spot

In good news, the world of travel is moving towards a greener, cleaner way of sashaying across the globe. Trufflepig is right in the scrum on these efforts. We are tickled pink that whatever momentum Al Gore attempted, Greta Thurnberg is striking into a butterfly effect. But this is not an article about environmentalism or progressiveness in any way. In fact, quite the opposite. If it were up to me, I’d be writing these words with my hair quaffed into a pearl comb, seated in a hand-carved Savonarola armchair with an ink-dipped feather plume in hand. For those of you who relish the indulgence of running your fingertips over antique maps or the tangible act of dropping a handwritten postcard down the metal slap of a post office box, this one’s for you.

I recently requested membership into the (nerdy) Letter Writing Society of Toronto. Before they couldn’t, the group met every two weeks at Toronto’s first post office to roll around in the relics of paper, handwriting, stamps and saliva-sealed sentiment. It’s a curious lot of intellectuals who are prone to asking if anybody happens to have spare supplies such as stamp tweezers, magnifying glasses, watermark detector fluid, or a perforation gauge. It’s not your run-of-the-mill, bell-curve-average, greeting card crew. No way. It’s a curious assortment of personal historians who simply must share a DNA strand or two with the historical cartographers of yesteryear, the folks who crafted perspective on canvas with precision, curiosity, and intrepid exploration.

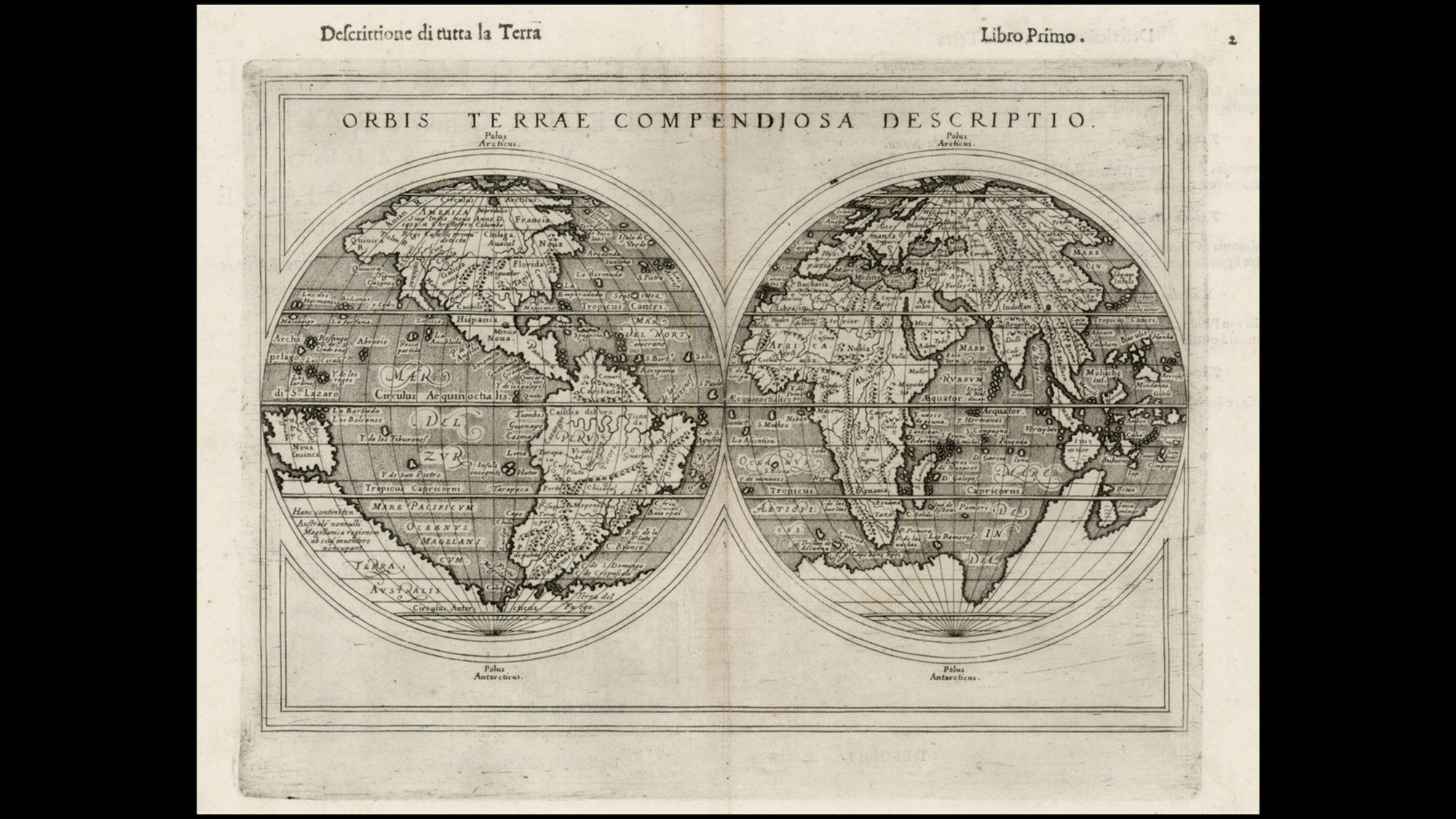

One of the most celebrated historical map makers is Urbano Monte, a once Milanese socialite who compiled a comprehensive 60-page world atlas back in 1537, on the backs of Mercator and Ortelius. This collection of maps was recently purchased and donated to the new map centre at Stanford where all 60 pages have been digitally assembled to create one large 10’ x 10’ map of the world. It is astounding to realize that they all fit together impeccably 474 years later. For a man who had every right to carry around a globe-sized ego, Monte didn’t even place Europe at the centre of the map, but rather Antarctica to demonstrate the circular nature of the earth.

Monte used his social clout to gain information on the swaths of land he hadn’t seen with his own eyes. Magellan himself slipped him a few notes on the sea lion/archipelago situation in the Tierra del Fuego. When given the opportunity to entertain Japanese diplomats, he evidently drove the dinner banter in the direction of napkin sketches between courses, which informed his seahorse-shaped landmass marked ‘Giapone’. Wealth and status aside, he earned his credibility with a mind that could master both linear and creative pursuits. Map makers of the day commonly filled in the gaps of knowledge with imagination and this is where our man Monte officially won me over. Say what you will about Siberia, but Monte added unicorns to his map of Siberia. In the Southern Ocean, he drew mermen frolicking while other seas further afield were teeming with monsters. Ships were a constant, fleets of them in fact, including a depiction of King Philip II of Spain atop a buoyant throne, hovering menacingly off the coast of South America. For a deep dive into the academic significance of this magnificent collection of maps, read this comprehensive essay by Katherine Parker, a historian of cartography.

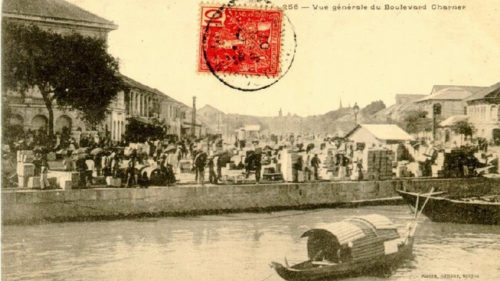

If you ask me, it is a travesty to see crowds shuffling right past the ‘Galley of Maps’ in the Vatican Museums as they stream through this 120 meter long hallway without looking up, like salmon spawning on their way to the Sistine Chapel. It will surprise nobody at this point in the article that unlike those with tunnel vision for the Great Michelangelo (rightly so), I stop to marvel long and hard at the 40 magnificent maps created by the cartography legend, Ignazio Danti. In 1580, commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII, Danti pocketed the new tools of the day – a magnetic compass, sextant and telescope – and put his math-professor-smarts to the test. He completed these vast and detailed masterpieces in less than 18 months flashing his command of artistry, scale, and detailed relief with impressive accuracy. Beyond the 40 maps on the walls, the ceiling is adorned with frescos to tell the visual narratives, the juicy bits of story, where the scope of a map drops off.

In our sounder of Trufflepig researchers, we jump at the chance to flip our sextants like switchblades and follow them to the ‘Siberia’ of our designated planning regions. The more remote the better. Into the centre of far flung villages, off to a smattering of remote islands, straight towards the sound of a rare dialect being sung out in folk song under golden light. A place on the map and a picture on the ceiling. It’s nearly impossible to outrun the scope of Google Earth these days, though a part of me longs to live in a time with geographical gaps on earth. When you could set out on a voyage heading east and from the bow of the ship, squint your eyes toward shore hoping to spot a school of mermen just around the bend. I strive to find a way to merge progress with artistry, WAZE with unicorns, environmentalism with handwriting as we navigate this ancient, modern terrain.

You can email Meredith here to riff on sextants and perforation gauges, or to simply plan a trip to Italy. Just don’t get her talking about the cracks in her granny’s lipstick kiss forever preserved on a vintage postcard from Lake Como circa 1965.