And to you, your wassail too

Here’s the thing about cider (or hard cider); it’s incredibly simple to make and anyone can do it. I have been consistently making average to disappointing cider for the last five years, but that’s not the point. You don’t need any special equipment or ingredients other than apples. You crush them, squeeze them and then leave the juice to ferment. Done. Granted, there are bits of kit, specialized yeasts and so on, that enhance the process and end result, but it’s a simple enough process.

Cider has enjoyed a renaissance of late, on the back of the craft beer and gin revival. Gone are the days of overly sugared, artificial flavoured, syrupy and sweet being the only offerings.

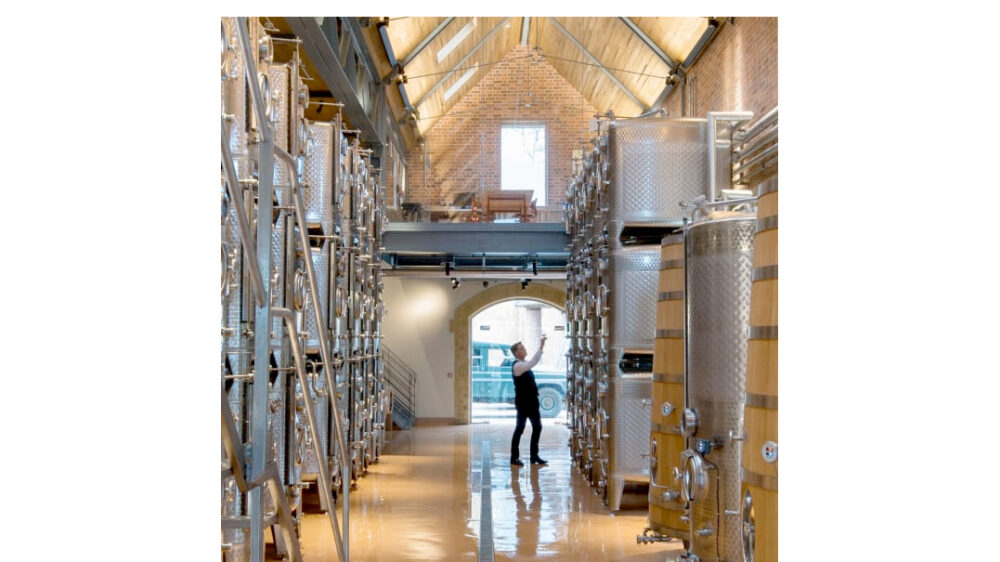

The much heralded Newt in southwest England, a splendid reimagined Georgian manor house-now-hotel boasts not only a recreated Roman Villa, sprawling gardens and a “Beezantium” but also a state of the art “Cydery” that marries state of the art production facilities with local apples. The resulting cyders are elegant, crisp and refined with a price point to match.

But aside from the craft offerings in bars and restaurants, cider is firmly rooted in the local, the village, the farm.

I first heard of the Chideock Cider Circle years ago , before the revolution, and as I looked harder at the countryside in the West country, the more I noticed the small crude signs, often hand painted, that pointed towards liquid apple goodness. A short diversion down country lanes, past cows and orchards, would often bring you to a simple shed attached to a farm, where the cider making continued unchanged in process for generations. The ciders were typically good, and as varied in profile as wine, according to the apple varietal used. Cider was such a big deal at one stage in England that the rather ominous sounding Long Ashton Research Station was created by the government, charged with studying and improving the West Country cider industry.

But science aside, it’s the perpetuation of tradition in cider that I fell in love with. Wassailing of apple trees still takes place, and older techniques of cider production are making a comeback. The typically French method of keeving, essentially a bottle-conditioned cider that is naturally effervescent, was always a little harder to pull off until the introduction of some basic science. The results have brought this form of cider making back to England, reinstating a technique that used to be prevalent.

The traditions are alive and well in Northern Spain as well, and are not limited to manufacture alone. Pouring the cider, after shaking the bottle a little, from above your head to a glass held below your waist ensures the perfect pour. And don’t expect a pint – but rather two fingers’ worth, to be sipped slowly before refilling. Any more than a couple of fingers’ worth and the delicate aromas will be gone before you finish the glass. These cider houses, often with restaurants attached, are preserving their interpretation of this ancient drink.

So next time you find yourself driving past apple orchards, take the time to pull off the main road and go explore.