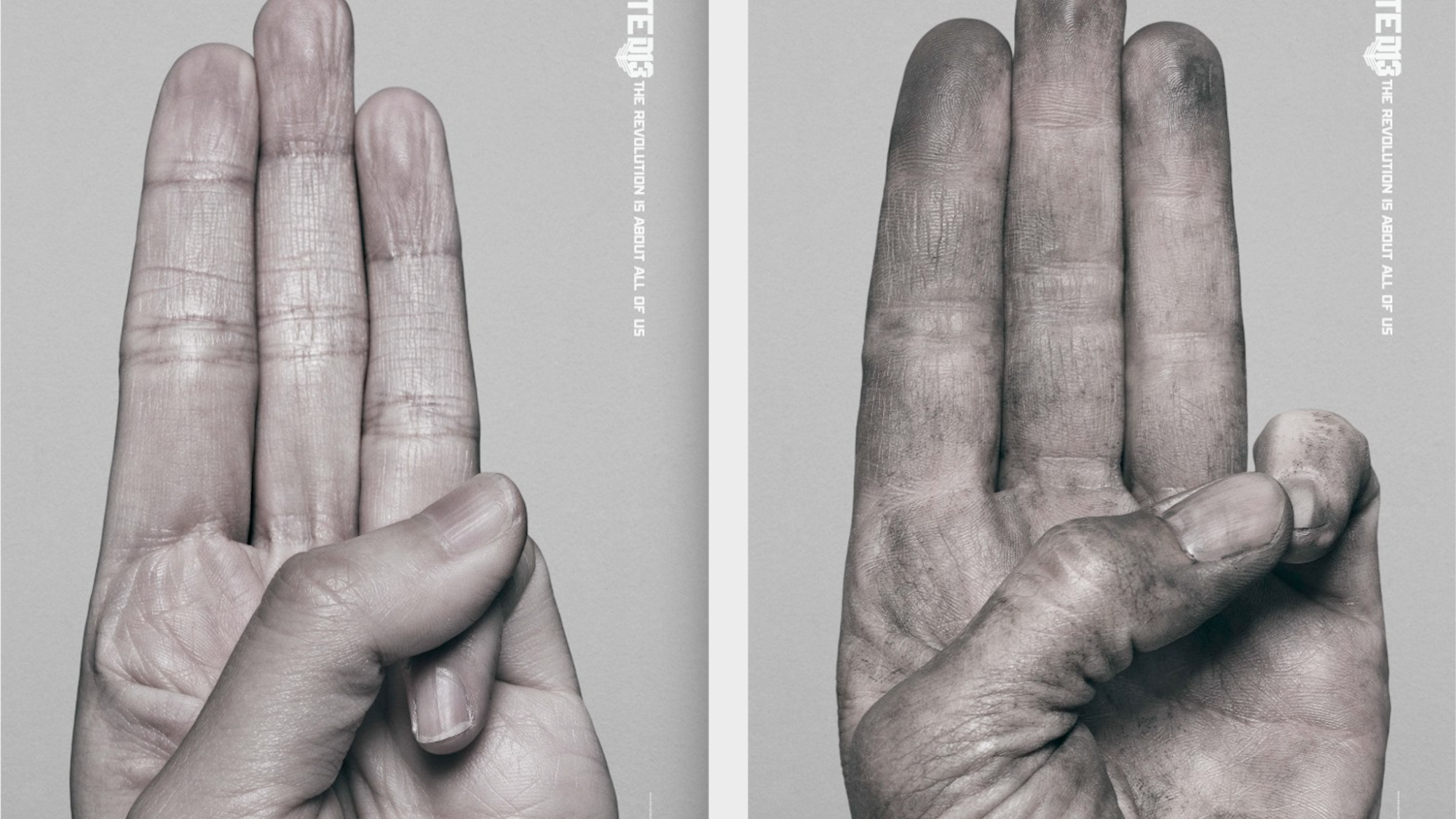

Pointer-Middle-Ring

Over the past few years a symbol has made the leap from movie into life. It is a salute with three fingers held high: pointer-middle-ring. It came from The Hunger Games, the series written by Suzanne Collins. Both a book and movie franchise, it is a tale following the life of Katniss Everdeen. Her name comes from a nickname of the swamp potato plant Sagittaria , which in turn came from Sagittarius the Archer, whose name means one that throws arrows. The three finger symbol at first is explained in the book like this: “It is an old and rarely used gesture of our district, occasionally seen at funerals. It means thanks, it means admiration, it means goodbye to someone you love.” Later in the story it morphs into a revolution sign as the characters in the story fight a wealthy ruling class.

From the pages and screen it jumped to reality in 2014 when the symbol took hold in Thailand after a military coup and a ban on gatherings. It was a unifying symbol of the pro-democracy movement that spring.

The 2015 ad campaign for the sequel film for Hunger Games used this real life popularity to an advantage when hyping up the new film. Posters were put up all around the world with a hand held high, pointer-middle-ring fingers united. The image stuck into the minds of the people of south east Asia. In early 2020, protests spread through Thailand again, and again the symbol was used as a rally cry.

Now we see it in Yangon. On Feb 1st 2021, The military in Myanmar staged a coup d’etat attempting to shut the doors on the country once more.

In my early 20’s my brother and I got into a fight about whether or not art could start a revolution. Specifically, if the theatre could be the vessel to start a movement. It was the third Friday in June and I know this because we were celebrating the life and music of Doc Watson, the famed Banjo player from Watauga County, North Carolina. The third Friday in June is Doc Watson Day in some parts. We were drunk, and the sun had set on both our ability to speak and our reason, but we were committed to our sides of the argument so we went to brotherly wrestling as a preferred form of communication. I argued that an idea or philosophy could be communicated so well during a play that something could transcend the art and incite a crowd to revolt. He argued the opposite, and that theatre is a reflection of culture rather than a driver.

A few years later I would find myself living and working in Myanmar, and learning how people there related to theatre, comedy and tragedy. There seemed to be less of a division between what was on stage and what was lived. Statues and icons are a good example of this. In North America, to see a statue is to see something that is intended to remind you of something else; a statue of Mark Twain is not meant to be Mark Twain in real life, it is meant to make you think about Mark Twain. In Myanmar, statues have a little more life to them. They not only represent the figure, they are, at least a little bit, a part or an extension of that being. So Mark Twain’s statue becomes an extension of the real Mark Twain, and needs to be fed, and clothed, and treated with the same respect one would give a living being. You can see this in the statues of Buddha as they will often have a plate of food in front or a cloth draped over the shoulders. I can’t help but think this transcends into all of the art forms, that there is a little more life to paintings, plays, books, and that icons in Myanmar breath, even if just a little.

Popular culture morphs and melts into movements and politics, being both affected by them as well as shaping it. Movies, plays, songs, books, all respond to a gathered need in a culture, as well as shape the ongoing mass conversation. I am thinking of adventure and travel texts from Patagonia that were surfacing in England around the time William Shakespeare was writing “the Tempest” thus inspiring his character Caliban the beast, or the myth of Shangri-La being born in James Hilton’s book ‘Lost Horizon’s mainly because Hilton was a fan of National Geographic articles written by Joseph Rock in the early 1900’s describing a wonderful valley in Yunnan China.

This is an old tale of influence. But it is different in Yangon at the moment. It is less of an effect and more of a collective cause.

When I first landed in Yangon in 2005 the sanctions were locked in place and the land was locked in time, like a closet of a long lost loved one unmoved. Movie posters were hand painted, old cars were fixed with parts fashioned out of melted metal, DIY was not a hipster choice, it was all there was. I noticed in all of my interactions a playfulness with wit and words, a humour that was dark and smart and critical of a regime one could not talk about outwardly. You weren’t allowed to say Aung San Suu Kyi’s name out loud so instead we all called her ‘the Lady’. It was easy to think of Harry Potter and he-who-must-not-be-named. It was a simple way around a law, playing with words and meaning. If you did get caught saying her name, you would disappear and end up in the hexagonal shaped prison in Yangon, named the Insein Prison; another easy connection made with the name Insein and the Insanity of the rules in a paranoid state.

Now, watching the way in which generation Z in Myanmar is fighting and protesting the military coup from Feb 1st, you can feel the same wit and pop culture references being pulled out with three finger salutes. The icons of the movement are not accidental, they are being discussed, and chosen, and we are all watching a generation that understands the power of images and ideas morphing and mixing, the cohesiveness a hand gesture can produce, the energy humor can spread in order to help moment move in the right direction, the downfall of the military regime.

Last week the streets of Yangon were filled with children’s toys called Pyit Tine Htaung which are little egg shaped painted rocks that are thought of as mischievous spirits. They were put in place of people for the protests for fear of being shot by snipers. The egg shaped toys roll upright when thrown down, and the translation of the name of the toy is Pyit (to throw) Tine (each time) Htaung (upright), which tells you more than any stump speech could tell, and all this communicated just by looking at it once.

The artist community is sending around templates for signs and instruction pdfs on how to build protective gear, and what symbols to print on them.

Choosing certain symbols from local folklore and others from international movie franchises is a deliberate choice. When trying to communicate both with the people of Myanmar in the countryside that there is a unifying idea, and at the same time with the people in the international community that there is a crime happening and help is needed, you have to use different types of symbols; you have to know your audiences.

The international audience might be hard of hearing though, or unwilling after the past 5 years of genocide news coming from Myanmar. Like all places, countries, regions, cities, peoples, relationships, and human history… it’s complicated, but I think after a year the world has just collectively had, we can all loudly say we understand ‘complicated’ and there is no need for sound bites or 10 word talking head answers. The Rohingya genocide isn’t to be ignored, and is a crime against humanity. There is a deep rooted racism in Myanmar (take a look here for more on that). Layering on military rule, and this particular military rule, will not help the Rohingya. Again, it is complicated, but worth the effort to understand.

When I talk with friends in Yangon they know they are alone, and they explain to me that they know the movement there has to deal with this coup assuming no one will come. They explain to me that messages and images are being chosen not in the hope of being rescued, but to spur understanding in the hopes of voices from afar reflecting back to Burma that they are being heard. And just like a joke needs a laugh, the witty humor used in protest fuels the drive of the movement. It is the fuel that is needed to keep moving forward, a message stolen from a movie in the language of those intended to hear it, with the hopes of having three fingers flash back, pointer-middle-ring, as a salute and recognition that we hear you, that you are not alone and must keep pushing forward.